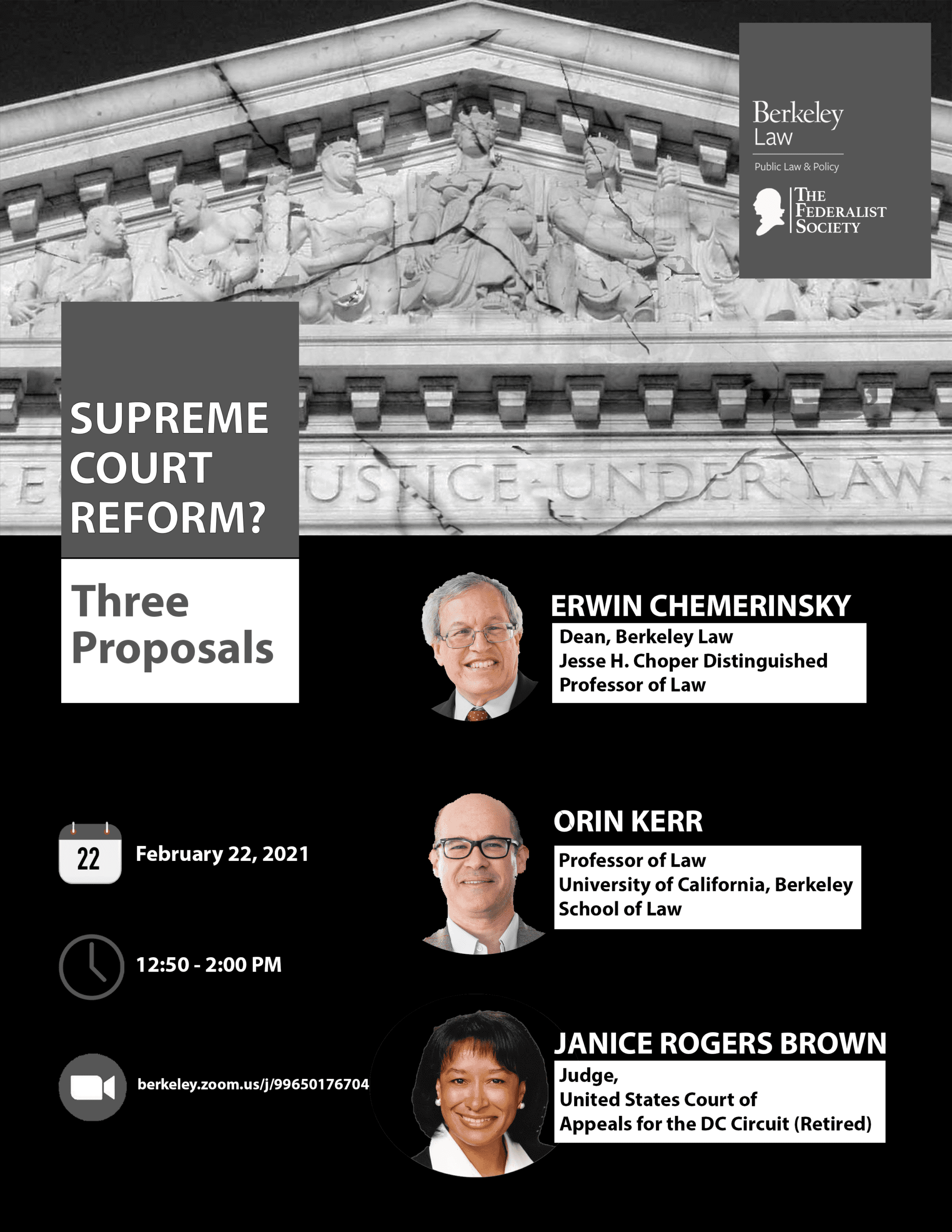

Supreme Court Reform? Three Proposals

Monday, February 22, 2021 | 12:50 – 2:00 pm

Zoom | Berkeley Law

Event Video

*Scroll to the bottom of the page for transcription*

Event Description

Recent Supreme Court confirmation battles and the 2020 presidential election brought to public attention various proposals to change the size of the Court and/or the tenure of the Justices. In this webinar, Dean Erwin Chemerinsky discusses arguments in favor of the expansion of the Court; Professor Orin Kerr examines the proposal for an 18-year limit for Justices; and former DC Circuit Court Judge Janice Rogers Brown explores proposals for mandatory retirement of Justices at the attainment of a specific age. Professor John Yoo moderates the program.

Panelists

Erwin Chemerinsky became the 13th Dean of Berkeley Law on July 1, 2017, when he joined the faculty as the Jesse H. Choper Distinguished Professor of Law. Prior to assuming this position, from 2008-2017, he was the founding Dean and Distinguished Professor of Law, and Raymond Pryke Professor of First Amendment Law, at University of California, Irvine School of Law, with a joint appointment in Political Science. Before that he was the Alston and Bird Professor of Law and Political Science at Duke University from 2004-2008, and from 1983-2004 was a professor at the University of Southern California Law School, including as the Sydney M. Irmas Professor of Public Interest Law, Legal Ethics, and Political Science. He also has taught at DePaul College of Law and UCLA Law School.

Orin Kerr joined the Berkeley Law faculty in 2019 after serving as the Frances R. and John J. Duggan Distinguished Professor at the University of Southern California Gould School of Law. From 2001 to 2017, he was a professor at the George Washington University Law School. Kerr has previously been a visiting professor at the University of Chicago and the University of Pennsylvania. An accomplished teacher, Kerr received the outstanding teaching award from the George Washington Law School Class of 2009. Kerr specializes in criminal procedure and computer crime law, and he has also taught courses in criminal law, evidence, and professional responsibility. He has written more than 60 law review articles, over 40 of which have been cited in judicial opinions (including seven articles that have been cited in U.S. Supreme Court opinions).

Janice Rogers Brown was confirmed to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit on June 8, 2005. From 1996 to 2005, Brown was an Associate Judge of the California Supreme Court. Previously, she served as an Associate Justice of the Third District Court of Appeal in Sacramento and as the Legal Affairs Secretary to Governor Pete Wilson. The Legal Affairs Office monitored all significant state litigation and had general responsibility for supervising departmental counsel and acting as legal liaison between the Governor’s office and executive departments. Her diverse duties there ranged from analyses of administration policy, court decisions and pending legislation, to advice on clemency and extradition.

John C. Yoo is the Emanuel Heller Professor of Law and director of the Korea Law Center, the California Constitution Center, and the Law School’s Program in Public Law and Policy at Berkeley Law. His most recent book is Defender in Chief: Donald Trump’s Fight for Presidential Power (St. Martin’s 2020). Professor Yoo is a visiting scholar at the American Enterprise Institute and a visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution.

Event Flyer

Event Transcript

John Yoo: Hello, I’d like to welcome everybody to our panel today put on by The Berkeley Law and Public Policy Program. And we have a I couldn’t imagine a more topical subject to discuss – three great panelists here to talk about reforming the Supreme Court. One of the major issues discussed during the presidential campaign was whether to change the size or the terms of service of the Supreme Court justices or the Supreme Court itself. We have with us three panelists who, if they were not on the president’s new commission, to make recommendations of reforming the federal courts ought to be on that panel. And probably – I would say – probably better thoughts than the members of the panel. And so we’ll begin in order, I’ll introduce them all now and they’ll each have about ten minutes to give their thoughts and then we’ll have a few minutes for them to discuss between themselves and then we’ll reserve at least twenty minutes at the end for questions that I’ll read off from the Q&A. So if you have any questions that arise please send them in to the Q&A. So to begin, we have Erwin Chemerinsky. If you don’t know who he is, you are in big trouble because he’s the dean of our school. So everybody here listening should know that we all, in a way work, for him. So first will be Dean Chemerinsky who, as you all know, is also dean the founding dean at UC Irvine and before that was a professor at Duke and at USC, and as I think he’s probably still holds a title as the most cited constitutional law professor in America. After him, we have Orin Kerr. If you don’t know who he is, then I don’t blame you because he hasn’t been here that long. Orin joined our faculty about, oh it’s about almost two years now, right? He’s coming up on two years. Orin is – some of you may know him – he’s a prolific writer and also in the public a great blogger and one of the leading scholars of criminal law and procedure in the country, particularly as it has to do with our new technologies. And then our third speaker will be Janice Rogers Brown. Many of us here in California have lived under the law that she promulgated, so you better know who she is. And if you didn’t, you better read about her. She was a justice of the California Supreme Court, and then after that a distinguished judge on the DC Circuit – often called the second most important court in the country after the Supreme Court – and is now a Jerasem residence with us here at Berkeley. I can’t imagine three better panelists and a great moment to talk about this most important of subjects, which is reform of the Supreme Court. So thank you all for joining us and let’s start with Dean Chemerinsky – please go ahead.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Thank you, John, for that kind introduction. My thanks to the Berkeley Program on Law and Public Policy for inviting me to do this and it’s such an honor to get to be on a panel with Orin Kerr and Janice Rogers Brown. I favor increasing the number of Supreme Court justices, though I don’t think it’s realistic right now. I want to make three points – first, nine justices is historic accident. The constitution doesn’t specify the number of justices on the Supreme Court – it’s ranged from five to ten over the course of American History. It started with five and so each justice was assigned to one set of states and the justice actually sat as a Court of Appeal justice. It was said that the justices then were writing circuit and ever since they’ve been known as the Circuit Courts of Appeals. As the country grew, they added another justice so it became six. But after the election of 1800 – when the federalist party of Washington Adams was defeated – congress decided to eliminate the justice position and reduce it back to five, showing the number of justices from early in American history had some linkage to politics. The country grew, and grew enormously, over the first half of the nineteenth century and each time another group of states was added another justice was added. And that’s of course so that the justice could continue to play a role in overseeing that circuit. And it got up to ten justices by the 1860s. I know we would find it strange today to think of making a conscious choice to have an even number of justices, but they did. In the late 1860s there was a terribly unpopular president – Andrew Johnson – he was impeached by the house. It was one vote of conviction short in the senate. It was at this time that the congress decided that they were not want Andrew Johnson to fill a vacancy on the Supreme Court, so congress said, “The next time there’s a vacancy on the court, we’re just going to eliminate that seat.” There was such a vacancy in 1869 and the seat was eliminated rather than Andrew Johnson was president of the time and it’s been nine ever since. That’s why I say nine is a historic accident – there’s nothing magical about the number nine. Any number would be arbitrary. There’s no study that’s been done that shows that nine is more efficient than seven or five, let alone eleven or thirteen or fifteen. In 1937 President Franklin Roosevelt proposed expanding the size of the Supreme Court this has forever been known as court packing. As everyone watching knows, in the early 1930s the Supreme Court was consistently striking down key new deal programs. Roosevelt won a landslide victory over Alf Landon in November 1936 and then he took on proposing saying, “Let’s expand the size of the supreme court.” So we had one additional justice for every justice over seventy. He had done the arithmetic, and that would let him quickly appoint enough justices to majority to uphold New Deal programs. To be sure there was a good deal of criticism of this, but it’s often gotten there’s also a good deal of support for it. But it all became unnecessary in March 1937 in West Coast Hotel versus Parish. The Supreme Court repudiated the Lochner decisions with regard to freedom of contract, and just a few weeks later on April 12, 1937 in NLRB versus Jones Laughlin Steel, the Supreme Court rejected the narrow views of congressional power that had led to the invalidation of New Deal programs. What happened? Justice Owen Roberts changed his mind. Roberts who’d in part of the majority in the Lochner decisions of the 1930s – in the limits on congressional power – decided to reverse course join with what had been the dissenting justices and create the new majority in fashion post 1937 constitutional law and uphold the New Deal programs. Did Roberts change his mind because of court packing? Had Roberts already decided to change his mind? We will never know the answer to that question, but Robert’s behavior is forever known is the switch in time that save nine. As we talk about expanding the size of the Supreme Court, there’s all sorts of lessons to draw from this, but I think the most important lesson is how just the threat of court packing likely an effect in changing the direction of constitutional law. Well this leads me to my second point that the Democrats should increase the number of seats on the Supreme Court to thirteen to restore ideological balance and to overcome what’s been Republican court packing. Since 1960 there have been thirty-two years with a Republican president and twenty-eight years with a Democratic president. In 2024, we’ll have had thirty-two years with a Republican president and thirty-two years with a Democratic president. Pretty amazing over a period that long – sixty-four years. Since 1960, there have been fifteen justices appointed by Republican presidents and eight justices appointed by Democratic presidents. Given the equal nature of representation of Republicans and Democrats in the White House, it’s hardly equal in terms of their ability to appoint Supreme Court justices. In part that’s just the historic accident of when vacancies have occurred. Richard Nixon had four vacancies in his two years as president. Donald Trump had three in his four years as president. But Jimmy Carter had no vacancies in his four years as president. But in part, this imbalance is because of, I think, unquestionably was Republican court packing. In February 2016 Justice Anton Scalia died. In March of 2016 President Obama nominated, then DC Circuit Chief Judge Merrick Garland to replace him. Chief Judge Garland – by all accounts – was impeccably qualified for the position, but Senator Mitch McConnell announced immediately there would be no hearings and no vote on Chief Judge Garland. And that was so throughout 2016. The act the Senate Majority Leader McConnell repeatedly said that, “In an election year, a lame-duck president shouldn’t be filling a vacancy on the Supreme Court.” He said, “It should be the voters in November by who they choose as president to decide who will fill a vacancy.” And many other Republican senators like Lindsey Graham and Ted Cruz said the same thing. On September 18, 2020 Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg died. I would have thought that Senate Majority Leader McConnell, senators like Graham and Cruz would have said, “Let’s follow what we articulated in 2016. Let’s wait since the presidential election is only six weeks away and the winner of that should fill the seat.” In what is even for the American political system stunning hypocrisy, immediately President Trump nominated Amy Coney Barrett – she was nominated eight days after Justice Ginsburg’s death – on Saturday, September 26th. And a month later on Monday, October 26th, the senate confirmed Amy Coney Barrett and she was sworn in that night. This, I think, was the Republican effort to control the composition of the Supreme Court as best they can. It succeeded. Where we are now is six justices appointed by Republican presidents and three by Democratic presidents. Of those six, five are very conservative – Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett. Roberts I would think of as a moderate conservative. And then there’s three left of center – Briar, Kagan, and Sotomayor who’s the most liberal justice on the court. If there is not an increase in the size of the Supreme Court, we are going to have a very conservative supreme court likely for another decade or two if not longer. Consider the age of the conservative Supreme Court justices. Amy Coney Barrett is forty-eight years old. If she remains on the court until she’s eighty-seven, the age with Justice Ginsburg died, she will be a Supreme Court justice into the year 2059. Neil Gorsuch is fifty-three. Brett Kavanaugh is fifty-five. John Roberts turns sixty-six at the end of January. Sam Alito will turn seventy-one on April 1st. Clarence Thomas, even though he’s been on the Supreme Court since 1991, is just seventy-two years old. I’ve always thought the best predictor of a long lifespan is being confirmed for a seat on the Supreme Court. So it’s easy to imagine these justices being together for another decade or two. So if progressives want to counter this, to restore ideological balance to the Supreme Court, to overcome the Republican work hacking, I cannot think of any solution other than increase the size of the Supreme Court. I realize the danger in this – if the Democrats do this now and make it thirteen justices, when this next a Republican president, Republican congress, they can make it fifteen or seventeen. But the alternative to me, of a very conservative Supreme Court for the next decade or two and the threat that it poses for basic rights and equality, justify the action. Third and finally, I don’t think this is likely to happen. Assume that such a bill is introduced into congress. We know that the Republicans in the senate will filibuster such a bill. The filibuster has been eliminated for judicial nominations – Supreme Court and lower federal courts – and for cabinet nominations, but it still exists for legislation. Some democrats – such as Joe Manchin from West Virginia – have said that they won’t vote to eliminate the filibuster. If this is true I don’t see a way that the Democrats can overcome a filibuster to adopt such proposal. Maybe the Democrats will be able to get together and eliminate the filibuster – just this or some categories of legislation – but at this point it doesn’t seem likely. So as of now it appears we’re gonna have a very conservative court and for a long time to come.

John Yoo: Thank you, Dean. Orin.

Orin Kerr: Great, delighted to be here with all of you. It’s wonderful to see everybody and to talk about this important question. I am going to argue that we should have eighteen year fixed Supreme Court terms – a constitutional amendment that fixes the terms at eighteen years and that also sets the number of justices at nine. I think that’s the best answer going forward and the reason why I think change is needed is that, for better or worse, the Supreme Court is a very powerful institution in American political life. Its decisions have a political valence reflecting the presidents who nominated them and the senates that confirmed them and the politics of the time in which a vacancy happened to arrive at the Supreme Court. And it seems to me that if we take the reality as as as fixed that the Supreme court is going to play a role in the political system, then it should be a politically accountable role. Then we should not have the direction of the Supreme Court essentially hinge on the health of an octogenarian and whether a particular person happens to be able to maintain their health for longer or for less long. We should have a more predictable system in which there’s a fairly reliable effect of any particular president’s election in any particular senate’s election on the direction of where the Supreme Court goes. So right now with the system of life tenure, you know, it’s it’s largely the direction of the Supreme Court is just which justice can hang on for how long and however many spots a particular president may get varies dramatically. So, you know, every election we say, “Oh this is going to be an important election for the future of the Supreme Court,” and you never know how many vacancies the president might have . We might have as Dean Chemerinsky noticed, you know, Jimmy Carter had zero vacancies and I think the maximum number – at least in the last hundred years or so – was uh FDR’s third term where he had seven vacancies – put seven people on the supreme court. And so a new president you never know how many they they’re going to get and you never know how long a particular justice may be able to stay on the Supreme Court or or if they want to stay on the Supreme Court. So um you know back a few years ago Dean Chemerinsky wrote, I thought, a very powerful op-ed arguing that then the Justice Ginsburg, then on the Supreme Court, should step down before the election of 2016 in light of the possibility that there may be a Republican president who would nominate a conservative to replace justice Ginsburg. Justice Ginsburg decided not to step down and of course passed away before the election of 2020, when then you know if she had lived longer she would have been replaced by President Biden and a Democratic controlled senate. The particular timing of unfortunately when she sadly passed away happened to be, you know, six weeks before the 2020 election. Similar with Justice Scalia – he happened to pass away in February 2016. If he had lived longer, it would have been a very different direction of the Supreme Court. It just seems to me a very odd system given the influence of the Supreme Court in American life that we would let the direction of the Supreme Court hinge so much on these questions of when a particular person, typically in their eighties, happens, you know, how long they live or how long they’re able to stay on the Supreme Court. So what what should we have instead? I think we should have a system where there’s fixed terms of eighteen years in which each president gets two picks. Probably maybe make it every two years. Every congress, the president gets a vacancy in the president’s first year and in the president’s third year and so we would have a predictable system where each president would have two picks and uh eighteen-year terms so our the direction of the Supreme Court would be fairly predictable. You would know for each presidential election there’s going to be two spots – this is what the Supreme Court will roughly look like at the end of this presidency and this is what the effect of each presidency will have and each presidency will have roughly the same impact on the direction of the Supreme Court. Exactly how you would do it – there are some interesting questions of what happens if a justice has to step down during the eighteen-year term, do you let the current president fill it or do you let somebody else nominate someone? This all have to be done, I think, with a constitutional amendment. So we can talk about different ways you might want to structure it, but I think that should then go along with the idea of fixed of fixing the the size of the Supreme Court at nine justices. It seems to me that if– the Dean Chemerinsky is exactly right. That nine is not a magical number, it’s a pretty good number it fits with possible eighteen-year terms and each president getting two picks. You’d want to have an odd number, of course, and exactly what the number is is going to be pretty arbitrary. But it seems to me that in the current system where that the number of justices on the Supreme Court is just a norm – norms can be broken and that can allow for any president to come in and any congress to come in and sort of change the number of justices to help their side or hurt the other side and that’s that’s not a stable system over time. And and specifically, I think the idea of of of sort of retaliating against what the Republicans did with Merrick Garland – you know first I take, I think I think Dean Chemerinsky is right that that then leads to the Republicans to retaliate the next time they have the ability to do so. Although if the democrats add four seats, the Republicans are not going to add four seats, they’re going to add like one hundred and four seats. So there will be a Supreme Court of like one hundred and fifty people or something like that. Good news for those interested in government jobs – you could have an eight you could have a permanent life employment, everybody gets to be on the Supreme Court. But and then, you know, how many can they confirm?Maybe they confirm sixty or seventy in that time and then it becomes the maybe the Democrats don’t see how many they can do. I think that’s a very unstable system, it’s not, it’s not not the right way to go and that having eighteen year terms where every president gets two fixing the Supreme Court at nine people is the way to make it relatively more democratically accountable. Now I completely agree that what McConnell did was cynical and hypocritical and blocking Justice Garland and then rushing through Justice – blocking Merrick Garland – and then rushing through Justice Barrett was clearly hypocritical. I don’t I don’t think that’s a terribly complicated point to make, but it seems to me that if if if the point is to kind of undo that then maybe, maybe the argument would be to add two seeds in order in some short-term capacity, to add two seats to the supreme court to sort of correct for that and impose a principled line on sort of undo that. But of course I think it’s interesting that – if I understand the Dean’s suggestion – would be to add four seats to ensure a a liberal majority on the Supreme Court of seven to six liberal majority. And as as Dean put it, that would ensure basic rights, restore you know sort of bring– and I worry that that is sort of a way of thinking of sort of making sure the results are what we want them to be. And so my concern is that if if we are setting the size of the Supreme Court to sort of be: here’s the size that gets us to where under the current politics, these are going to be the results that we like or we think are correct and you know the other side thinks their their side is correct, but we think our side is correct, I worry that that’s just that’s just a political sort of just changing the the the political nature of the Supreme Court until finally, you know, we there are hundreds and hundreds of Supreme Court justices and then and then maybe we have a constitutional amendment. It may be that that’s kind of what we’re going to be destined to have – sort of instability until until we have term limits and a fixed uh uh fixed number of justices. But but I think ultimately that’s the best way to do it: nine justices, eighteen year terms, every president gets two, a vacancy comes up every two years, and there’s a political accountability to in, and we don’t have to have the direction of the Supreme Court hinge on whether a particular justice wants to step down or whether they want to stay on. After eighteen years they’re off, thank you very much for your service, someone new comes on, and it’s more politically accountable that way. I think that’s the the better way to do it and to sort of get beyond, ou know, settle some of these these norms and and in in in constitutional law. Thanks I’ll stop there.

John Yoo: Thank you Orin. Judge brown.

Janice Rogers: Thank you, John, and thank you to Berkeley’s Law and Public Policy for inviting me to participate. It’s a it’s an interesting issue. You said it was topical. I think it does have that ripped from the headlines quality, but in reality this question about the structure of the Supreme Court has been around for a long time. My proposal is undoubtedly the least provocative of those that are being presented today. It’s not exotic and it’s certainly not new. What I would propose is that we do something that just about every other Western democracy has already done, which is to have a mandatory age or retirement. The question whether there should be a mandatory age for Supreme Court justified justices actually goes back to the beginning of the Supreme Court in the earliest days of the constitution when the federalists and the anti-federalists were arguing about what the Supreme Court should look like and what that would mean. This is an issue that Hamilton, writing as Publius in the federalists, specifically considered at that time New York required judges to retire at age sixty and Hamilton made it clear that he thought sixty was too young and he said, “There’s really no problem because so few outlive the season of intellectual vigor.” So he did not think that you needed to be concerned about that. The other thing that he brought up was in a country where few are wealthy and pensions are unreliable, it was really inhumane to put people out of the job when they were unlikely to be able to find another one that would keep body and soul together and he dismissed what he said was the imaginary danger of a superannuated bench. And perhaps he was so certain about that because lifespans then were considerably shorter. But there’s always been concern about judges becoming mentally incapacitated, unable to serve, and a number of chief justices going all the way back to the 1700s have thought that one way to solve this problem would be to have a mandatory age for retirement, perhaps seventy, perhaps seventy-five, or something like that. We are probably the only country that doesn’t have that at this point. In Germany justices have to leave at sixty-eight. In the United Kingdom at seventy. In Canada and Brazil it’s seventy-five. So and we have thirty-one states that have mandatory retirement age. So we have a lot of experience with it. So to me, the fact that this is not new, that we’ve looked at it, that we know whether there are unintended consequences is actually a virtue and not a problem with with this idea. So of course uh it will not solve um the problem that everybody has really touched upon while we’ve been talking which is the politicization and polarization of the court. Which is which is a thing that’s really, I think, troubling people. And I’m not sure that any of the things we’ve proposed would actually fix that problem. But putting that aside, it seems to me that mandatory retirement does have a few things to recommend it. It’s neutral and non-political and although some degree of politics in the court is inevitable – and I suppose unavoidable – I think in deciding how to structure the court, we should try to avoid doing things that are overtly political or that move the court in that direction. The whole reason for life tenure was to have an independent judiciary. I also think that it can be presented as a purely good government initiative – there’s both historical and empirical evidence that cognitive decline is a function of aging and we can’t really um get away from that. I don’t like that idea much myself, I actually kind of like P. J. O’Rourke’s moon that age and guile will beat youth in a bad haircut any day. So I would like to deny that that’s the case, but in reality it’s true. Those of you who are twenty-somethings though, don’t feel too smug because cognitive decline begins in the twenties, it just accelerates as we get older. So but there’s a there’s been a quite a bit of work done on this and the National Bureau of Economic Research in fact has done a longitudinal study looking at judge decisions from forty-seven to ninety-four. So it’s a really good swath of decisions on to give them data points and they they used state Supreme Court judges, of course, not the federal courts. But um the results of that analysis are are pretty robust and they seem to show that, you know, there is a positive impact from mandatory retirement at both the team level and in terms of the younger judges. So there’s a lot, I think, to recommend it. And it may have the consequence of making this a job uh the capstone of a career rather than an anointing. And that may do some good on its own. The court has actually looked at this issue – the Supreme Court not dealing with Supreme Court judges, but in a case called Ashcroft v. Gregory, the they considered the Missouri mandatory requirement and Justice O’connor said that, “The people of Missouri had a legitimate NDA compelling interest in maintaining a judiciary fully capable of performing the demanding tasks that judge as much must perform.” She acknowledged it’s an unfortunate fact of life that physical and mental capacity diminish with age and that people may therefore wish to replace some older judges. Well if that’s true for state court judges who also have demanding jobs, the same could certainly apply to the Supreme Court. And while lower court judges in the federal system have the ability to take senior status and take some of the pressure off, that’s not available to justices of the Supreme Court. So I understand that judges may be reluctant um to retire and give up their work. It’s not an easy thing to do if it’s work that you love, but back in 1928 Chief Justice Charles Evan hHghes said that, “The importance of what the Supreme Court does means that we should avoid the risk of having judges who are unable to properly do the work and insist on remaining on the bench for people like me. The appellate court is the best job in the world. So it’s not an easy job to say goodbye to.”And that may be why Judge Posner observed in 1995 that the judiciary is the nation’s premier geriatric occupation. But it probably shouldn’t be. And that brings me to what I think is the final point in favor of a mandatory retirement rule. I think most judges not only love their job, they want to do it well and judges are usually drawn from that subset of lawyers who are already neurotic overachievers and when we see a colleague who’s been there a little too long and we all know it we are mortified on their behalf. And some of us are worried that the same thing will happen to us and that depending on what fails us we may not even know it. So I think the last benefit of mandatory retirement is the refreshment of a new beginning. Age is arbitrary line. For some of us a mandatory retirement might come just in the nick of time, for others it might be decades too soon. In 2006 I went to Israel to participate in a conference that was in honor of Iran Barack who was retiring as president of the Israeli Supreme Court at that time. He was highly regarded in Israel – somewhat I think characterizes that nation’s John Marshall. Israel doesn’t have a constitution, but they had a basic law and he had been very instrumental in making that basic law into a charter of rights. And everyone wanted to honor him and celebrate his retirement and I remember thinking that he was being very shallowly treated. After all he was still a very able judge and he was just kind of being put out to pasture. But when I asked him about this, he did not agree with me at all. He had taken the job knowing that there was a mandatory requirement retirement rule, he knew exactly when he was going to leave, and he had planned what his transition would be. And so he was looking forward he said to coming to the us and teaching at Yale, where I think he still might be. But that kind of changed my mind about this mandatory retirement it may not be a punishment, it can be a fresh start. And while being neutral and non-political, I think, it may still solve some of the problems of the morbid concern about the health of elderly justices, the concern about the ability to do the work, it might eliminate the gamesmanship that goes along with people deciding when they will retire based on who’s in office or who might be. So for all of those reasons I think it is a proposal that has some potential. I think it would require a constitutional amendment, but it is so neutral and low-key that it might be possible to do it and that would generate a discussion about the Supreme Court that’s maybe long overdue so.

John Yoo: Thank you Judge Brown. Before we get to questions, I want to invite any of the panelists – maybe we’ll go back in order – to respond or discuss any points you might have. Before we do, I just want to personally say that none of the arguments about the incapacities of elder judges apply at all to legal faculty. We think we can all agree professors can continue in their work until the day they die. But uh let’s go on. Dean Chemerinsky.

Erwin Chemerinsky: So real quickly. Orin spoke of – and I think these are exact words – “Pejoratively making results what we want them to be.” That’s exactly what the republicans did in blocking Merrick Garland and rushing through Amy Coney Barrett. And the question is what do we do about it now? Orin says this is going to lead to hundreds of justices. There’s no indication that that’s likely to happen, in fact there have been states where there was an increase in the size of the state’s Supreme Court for exactly the kind of reasons I’m talking about so as to achieve ideological balance. The retaliation that Orin describes didn’t happen in those instances. But more important to me is the question of what’s the alternative? If you believe as I do – that the current court is going to be a threat to the most important rights and equality – do we simply accept that for the next ten or twenty years? And if we don’t want to accept it, what is the immediate solution? In terms of term limits, I agree with Orin’s proposal – I would simply add life expectancies a lot longer now than it was in 1787. In 1787 the average life expectancy was thirty-six years old. Clarence Thomas was forty-one, forty-three when he was appointed the court in 1991. If he stays until he’s 90 years old, that’s forty-seven years of justice. So it doesn’t sound partisan. Elena Kagan was fifty when she was confirmed. If she stays ’till she’s ninety. That’s for forty years. I agree with Orin – that’s too much power in a single person’s hands for too long a period of time. I think there’s two really interesting questions here. One is: could this be done by statute rather than a constitutional amendment? Some such as Professor Kermit Roosevelt at the University of Pennsylvania think we could do this by statute by just having the justices remain with the title justice collecting the salary and sitting on Court of Appeals cases. I think that that would require a constitutional amendment because I think it’s changing the fundamental nature what it means to be a justice, but there is that proposal that’s worth mentioning. Also all of the proposals that i’ve seen would be prospective only. They wouldn’t apply to the current justices on the court. I’m not sure why that has to be so, but if it’s true that it’ll be prospective only. It even makes to me more important thinking of another solution like increasing size. Finally in terms of what Judge Brown said: I have to disagree about one thing. I think the best job in the world is being a law professor.

John Yoo: Notice that he did not say dean.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Now you have one feeling about being a dean, that’s a different question. It depends on the day you talk to me. But being a law professor is the world’s greatest job. I would be a hypocrite then since I’m about to turn sixty-eight years old to endorse mandatory retirement for others at age seventy. I think also eighteen year non-renewable terms would essentially accomplish the same thing and I think might do it better. I worry that with a mandatory retirement age of seventy it would encourage presidents to appoint younger justices whereas eighteen-year, non-rural terms is much more likely to make it a capstone of a career. And I have to admit that I’ve come to believe that there is some wisdom that age brings and having justices more towards the end of their career would be a better thing rather than younger justices. I think there is a problem of judges, professors who suffer cognitive decline, but I think we should deal with that problem with those who suffer cognitive decline, but there’s others – including on our faculty – who are well beyond age seventy who are as sharp as ever. Cognitive decline is not universal and I wouldn’t want a rule that says that Justice Stevens wouldn’t have had his last twenty years on the court or Justice Ginsburg her last seventeen years or you can pick the other justices who went on beyond age seventy and served great distinction and effectiveness.

Orin Kerr: Great. So Erwin Chemerinsky, this is great great interaction. I’m appreciating the exchange and I just wanted to offer a couple thoughts in reply. It seems to me that we should expect politicians to be politicians, right? So there presidents are going to nominate justices and senates are going to confirm or not confirm based on what serves their perceived political interest. And I take the issue that we’re figuring is what is the structure that we should create under the constitution to channel their decisions, their political actions? And so my concern is that if we create a system in which it allows– if if we have our view being let’s pursue our short-term political interest, then that’s just going to encourage them to always keep pursuing their short-term political interest in a way that is is is unstable. So so it seemed, you know, an interesting question too is what would happen if it were the the shoe on the other foot politically? And instead of it being McConnell, you flip and have it be a Democrat in charge of the senate who’s making these decisions? And I think it’s an interesting question. Imagine the future of the Supreme Court, the future of abortion rights, the future all of the rights that are at stake were potentially going to be sacrificed, but it was like a question of whether the senate should just nonetheless go ahead and confirm a a Republican nominee because it would be kind of unprincipled not to do that in light of pre-existing norms. My expectation would be that basically the Democrats would have done the same thing that McConnell did if in those shoes because the stakes would have been perceived to any politician as being so high. We don’t know that but but I kind of assume politicians will be politicians and and I guess i extend that to the idea of if if four seats are added to have a seven six liberal majority, you know, Dean Chemerinsky said, you know, there’s no sign that Mitch McConnell would then do sort of keep going and and add forty seats. And and I guess I would say my assumption is that Mitch McConnell would do that which you know furthers the political interests of the Republican party and that that that that he would do that to take to, you know, that that basically in in the tit for tat, as soon as you sort of up it to “Okay let’s also change the size of the Supreme Court,” that that doesn’t stop. That goes until each side maximizes each the political effect of that and and so I think you need a constitutional amendment to fix that and take that variable out and and and should do it at the the same time that you fix terms at eighteen years. And and I agree with Dean Chemerinsky that I think that that basically handles the question of mandatory retirement age. You can have again sort of roughly fifty year old people that are nominated, they retire in their late sixties and that that would sort of deal with the the potential concerns with cognitive decline, and also prevent the incentive of, you know, basically nominating law clerks to be on the Supreme Court. It’s like, “Oh you were a great law clerk.” You know you’re you wouldn’t want to have, you know, twenty-five year olds unless you’re twenty-five that probably sounds pretty cool. But but I worry that a a mandatory retirement age of seventy would just push the age down of people that are nominated and because in a current age where you know we’ve sort of seen norms get stripped away over time I you know i i wouldn’t be surprised that that would happen if we had mandatory retirement age or something close to it great.

John Yoo: Thanks Orin. Judge Brown.

Janice Rogers Brown: Well I have to admit that I can certainly see that that there is a possibility that a mandatory retirement age would um still lead to political gamesmanship that is that, you know, people would try to figure out how to maximize the amount of time that someone would be on the court. When the federal courts decided to have, you know, a clerkship hiring process, that was one of the concerns because judges were hiring young, you know, earlier and earlier without any information about those people. And so at one point a colleague said, “You know if this keeps up we will be deciding on the basis of Apgar scores who we will hire as person.” For those of you who don’t know, an Apgar score is something that is given for an infant when they are first born deciding whether they, you know, are all there and everything is working as it should. So there is always the possibility of, you know, perverting or distorting what it is that you’re trying to accomplish with the mandatory retirement age. But I think that manipulating that is perhaps less likely than what is going on now which is that people nominated are getting younger and younger because they want them to have forty or fifty years to spend on the court. So I’m not sure that eighteen-year terms solve that, but if it does get us more wisdom and more experience. I think that’s that would be a good benefit. The concern that I have um with both of these approaches is that it’s perhaps too overtly political. That is to say the reason for a life tenure in the first place and the whole discussion that we had about independence of the court was to separate constitutional law from politics and I think, you know, that distinction has become impossibly blurred. I don’t– Dean Chemerinsky says, “How do we fix that? You know if there is and an imbalance.” But but it seems to me that the real problem is that that we shouldn’t be talking in those terms. We have a constitutionally limited government and the judiciary should be about determining what that requires and not about following some particular political agenda. So I think I like the mandatory retirement approach because we know a lot about it. All of the others have the devil and the details and the potential for uncut unintended consequences that we simply have no idea how those will work.

John Yoo: Alright, thank you. I’m gonna– we’ve got, so and I see so many participants and we’ve got already seventeen questions in the queue. I’m going to try to summarize some of them together, there are several common themes. The one – and this is asked by Steve Hayward who is a fellow with the center – but it’s representative of several other questions which is: wouldn’t this be, all the various proposals, wouldn’t it be as unpopular as what happened in 1937? You know Dean Chemerinsky mentioned the court failed court packing plan in 1937 because, and this ties with what Judge Brown just said, it it not only it accepts and almost codifies this idea that law and politics are now becoming the same thing and so we should have some kind of regular representation on the court rather than considering law and politics to be separate and different. So I’ll throw that out to anybody you’d like to answer.

Erwin Chemerinsky: I think we have to be very careful about law and politics being separate. There’s a way in which yes, of course they’re separate. No one can go and lobby supreme court judges or judges at any level in the way in which they can lobby legislators. We accept vote trading among legislators but we wouldn’t accept vote trading among judges on an appellate court or a Supreme Court. But law has always been – and constitutional law – has always been a function of who are the justices are there. There’s tremendous discretion especially on the Supreme Court and how it’s exercised is a function of the ideology was there. Marbury versus Madison wouldn’t have come out the way it did but for John Marshall being chief justice at that time and wanted to advance a particular ideological agenda. The decisions of the Lochner from the 1880s to 1936 wouldn’t have come out that way but the ideology of the justices. Why did the Republicans block Merrick Garland’s confirmation? Why did they rush through Amy Coney Barrett? Because they know that the outcome in so many Supreme Court cases is a function of the ideology was there. It seems to me wrong to say: oh no there is law that exists with regard to the constitution that’s completely apart from the ideology of who the judges are. That’s impossible for so many reasons: the constitution is written in very broad language, also no rights are absolute. Inevitably it comes down to the levels of scrutiny. What’s a compelling or an important or a legitimate interest? There’s no way to answer those questions apart from the ideology of the person the life experience of who’s answering there. So I fully embrace that who are the judges are going to determine the outcomes. I have a ninth circuit argument a week from Thursday morning. The first thing I did when I woke up this morning was go online to see who’s my panel. That’s because i know the identity of the judges matter enormously in terms of outcome of cases.

Orin Kerr: John, if I could take this now. So first I would say that the, you know, the idea of term limits for Supreme Court justice actually is is hugely popular. It’s something it pulls at something like seventy- five percent when when people are asked this granted you never know any particular proposal might be different. But the idea of term limits for supreme court justices actually is quite popular. I completely concede that the proposal is premised on kind of a sad assumption which is that the Supreme Court is going to be a political body or at least its decisions are on the whole going to have a political valence reflecting the politics of the people who nominated and confirmed them. It would be much better to be in a world where that was not the case – I happen to love it when it’s when a justice votes against their the president who nominated them or you get somebody who’s sort of usually conservative who votes in a liberal direction or a liberal votes in a conservative direction. I love that because it’s a sign that there’s actual law going on, instead of just justices being influenced by by ultimately the politics that led to them. And the problem is the political actors that do the nomination and the confirming they have political incentives, right? So a president is – a liberal president – is not going to nominate a conservative and they’re not at least intentionally so and a conservative is not going to– the the the politicians are going to have incentives generally speaking to nominate Supreme Court justices that that advance a certain set of political views which is going to reflect the base of their their their their politics. So it seems to me that that’s just the unfortunate reality and we can either have a system where we pretend that isn’t the case and have the direction of the Supreme Court hinge on the health of a single person and whether they live until next year or the year after that or we can just kind of acknowledge: yeah that it turns out that the way the system was designed happens to be falling into political lines and we happen to have a pretty predictable political valence to vacancies and we should we should make it predictable because we we’re not likely to change it. Politicians are going to act in in ways that further their their politics and that’s that’s just the way the world works and we have to work work with that. I think that’s that’s at least the premise of my framework of thinking of it.

John Yoo: Judge Brown, do you have–

Janice Rogers Brown: Well certainly it’s true that politicians are going to be politicians, but U think there’s a difference between a politician choosing someone whose judicial philosophy is congruent with what that politician believes. I mean we all – I think – would acknowledge that there are at least two constitutions in America and that they’re really quite different. So saying that a politician would, for instance, if they were someone who preferred the founders constitution that that person would choose someone then who was maybe judicially restrained and unlikely to find lots of new rights as opposed to someone who would prefer a living constitutionalist – somebody who quite willing to evolve the constitution. I suppose those things are political in one sense – that is to say they reflect that, but the idea of making judges themselves political actors I think that’s actually somewhat different. Now it may be that there’s no getting around it – that that’s what we have and we can and we can never go back. And we’re forced in that case to make a virtual of necessity, but my own sense would be that that’s not where we should be trying to go. You know I don’t know that any of these proposals, you know, will actually um be effectuated, but should we think I think we have to decide what it is we’re trying to accomplish with these proposals. Do we want a Supreme Court or a court system that is just a component of the political realm or do we think there is a reason to try to preserve something different?

John Yoo: Okay there’s a two more questions that continue on this theme one by Lawrence Thai and then once from an anonymous attendee. So the question essentially, I think, is more aimed at the Dean which is: if you are to change the number of judges on the Supreme Court doesn’t that open the door as it were to even more politics coming into the court? And so you were alluded to one, what’s the stop uh continuous expansion of the court or reduction of its size for a political ends or does it just create instability in the judicial system that we don’t want even though we accept it in the or in the parts of the government that are, you know, elected?

Erwin Chemerinsky: I want to separate two concepts with regard to opening the door. One is does it open the door to ideology being more a part of what the Supreme Court does? I don’t think you can open the door more to it. I believe that in the crucial cases that are decided by the Supreme Court it very much comes down to ideology. Why did Justice Ginsburg and Justice Scalia so often degree disagree in the most important regards most important cases? It’s not that one was smarter than the other, it’s not that one knew the constitution better than the other. They had vastly different ideologies. The difference between Justice Barrett and Justice Ginsburg is all about ideology – that’s why the Republicans blocked Merrick Garland, that’s why they rushed away Amy Coney barrett Because because they know who’s on the court makes an enormous difference. So I don’t think expanding the size of the court is going to increase the presence of ideology in its role in deciding cases. On the other hand, expanding the size of the supreme court well could open the door to when the Republican president, Republican congress they’ll increase the size of the supreme court too. But what no one has answered is: if you have my values and if you’re afraid of what this very conservative Supreme Court is going to do in the next couple of decades, what is the alternative to that but to expand the size of the Supreme Court? Unless you’re willing to just accept that this threat to liberty this threat to equality is going to be there for the next two decades. So to me: yes I see that risk, but I see it as justified in light of how serious I see the threat of having a majority of Thomas Solido, Gorsuch Kavanaugh, and Barrett as being.

John Yoo: So several questions aimed at Judge Brown and Orin Kerr for their discrimination against the elderly, it appears. Several of the questions are: aren’t some of our better judges older? Don’t we want our judges to have wisdom? If you’re cutting it off at sixty-five or you’re right requiring constant right replacement after eighteen years, aren’t you depriving the judiciary of the benefits of wisdom from the old? You don’t, this has got to be someone who’s not a student. Students never think this way. But and then a similar question is: when you if your aim is to you know achieve that, are you making certain assumptions about the appointment process? For example that someone’s ideology never changes from when they’re appointed to, you know, longer on the court or even that we can place them into different boxes? You know all these questions assume that the selection of a judge is about representation and the way we think of selecting congress. Several of the questions are: aren’t you depriving the judiciary of a lot of benefits when you start to think of judges that way. So I think that’s more aimed at Orin and Judge Brown.

Janice Rogers Brown: Okay well as to whether I’m guilty of ageism – I hope not. Being an old person myself, the interesting thing about, you know, applying the anti-discrimination laws to to old people is I think we really haven’t thought it through. If we are around long enough, all of us will be old. And so I don’t think it’s really a question of discrimination, I think it’s I mean I mean that’s the way we set it up and there are reasons for that, but it’s really a question of, you know, ability, energy, physical health, stamina all of those kinds of things. And it’s quite true that everybody ages differently and there are people, you know, who I would welcome as colleagues on a court in their nineties and there are other people who start to fade at sixty. And so that line is always arbitrary, but because it’s arbitrary I think it is not discrimination. It may cut off some people from the judiciary who have much more to give but that’s okay. They can do other things. And that that’s what struck me about president Aron Barack – that he was that happy to have that fresh start and it was something to look forward to. So we ought not to look at it as, you know, punitive yeah in in any way. It it allows you to order your life in a way that’s maybe actually helpful. I forgot what was the other part of the question.

John Yoo: No no that’s that was– Orin.

Orin Kerr: Yeah so I want to take the other part of this which is, you know, what about justices whose views change? You know I suspect we’re probably past the time when the ideology of justices is likely to change in part because the the recognition of the political role of the Supreme Court has led to a priority of making sure that the folks that are doing the nominating and the confirming of judicial nominees have some idea of the of the ideology of various nominees long before they are nominated. So there used to be a time, you know, I think Justice Souter is an example of this maybe Justice Blackman as an example of this where actually they did that the president’s not making the nominations really didn’t have much of an idea of where the justices were um and and, you know, Justice Souter really had not confronted the questions that the Us Supreme Court deals with, didn’t have particular views. And there was sort of a well, you know, I think when when George H. W. Bush nominated him, there was like well Sununu says he’s okay and maybe this will go all right. I think we’re now in a world where, you know, the the political importance of this has been recognized and so the political actors ensure that the folks that end up being nominated have used that are known to enough insiders that effectively the ideologies are going to be relatively fixed. That doesn’t mean, you know, over time what is a liberal and a conservative can change . I think Felix Frankfurter is the classic example of this where he was a liberal when he’s nominated to the Supreme Court in the 1930s and by the 1950s he’s considered a conservative because the issues before the court had switche in a lot of ways and he was consistent over time, but just his views had a different ideological valance given the different issues before the Supreme Court in the 1950s and the 1930s and 1940s. But but I think probably the idea of justices sort of evolving over time that, you could still have some of that but I suspect we’re going to see less of it. And I should say just going back to one an earlier point – I mean my own view I would prefer the Supreme Court to have a lesser role in American life and for presidents to look beyond ideology and nominating and for senates to confirm anyone who is, you know, I would say senate should be quite deferential to the president’s view. My own preferences of how the Supreme Court should work are like not on the table, unfortunately. And so I’m taking the sort of reality of what is as my my framework for thinking about this problem.

John Yoo: Okay great. Last question and I’m trying to pull together several different questions with this so for but they’re very similar. So with Orin who’s in in favor of term limits, the question is: well all the things you said about term limits, would you be willing to apply them to the other branches too? Why not have term limits for members of congress? We do have term limits for members of the obviously for the presidency. And then the variation on that for the Dean is: would you be willing to allow those same kinds of flexibility about institutional size and membership with the other branches too? Should congress be more willing to change the number of members of congress? Should we allow changes in the agencies their size and who gets to head them based on, you know, political change? And then it’s only five minutes left so you could limit your answers to two and a half minutes each, then we can finish on time.

Orin Kerr: I would just say um i favor fixed terms for the president and fixed terms for the Senate and the House, and we have them of course, right? We have presidential terms for four years and the House is two and the Senate is six, so we already have fixed terms, you know. We don’t have to face a question of how often somebody is reelected. of course with with justices they’re not reelected. It’s just a question of how long is the term. We shouldn’t have fixed we shouldn’t have life terms of any of these of these folks, so I’m really just talking about making the rules for judges be the same fixed terms as they are for all the other individuals.

John Yoo: You’re on mute, Erwin. That’s that’s the way I like Erwin best, but go ahead please. Unmute yourself.

Erwin Chemerinsky: We of course do have a way of removing members of congress when they’ve served too long – it’s called elections. We don’t have something like that with regard to Supreme Court Justice or Federal Court Appeals and district judges. I would favor an expansion of the senate. I think the fact that it’s two senators per state regardless of size is tremendously anti-democratic. It makes no sense in our modern world senators representing forty-four percent of the country are who confirmed Brett Kavanaugh for the Supreme Court. Senators representing less than thirty percent of the country sometimes can adopt laws. So I would favor an expansion of the senate having allocated by population. In terms of the house there’s – nothing magical about the current number of the house. I think it’s worth thinking about should we increase the size of the House to have. More representation more House members, mean smaller districts, which I think is better for democracy.

John Yoo: Thank you. Well I’m sorry we couldn’t get to – there’s still twelve questions – I’m sorry we couldn’t get to all of them, but I wanted to thank Erwin, Orin, and Judge Brown for joining us today. Thanks for to all of you for joining us and participating so vigorously and I’m glad we had this uh timely– oh but as Judge Brown reminded us so age-old question as long as well as a timely question and I hope everybody can join us again for our next event. So thank you very much everybody for joining us and we’ll be posting this video online within a day or two so people outside Berkeley can enjoy it as well. Thank you very much everyone for joining us and have a good day.