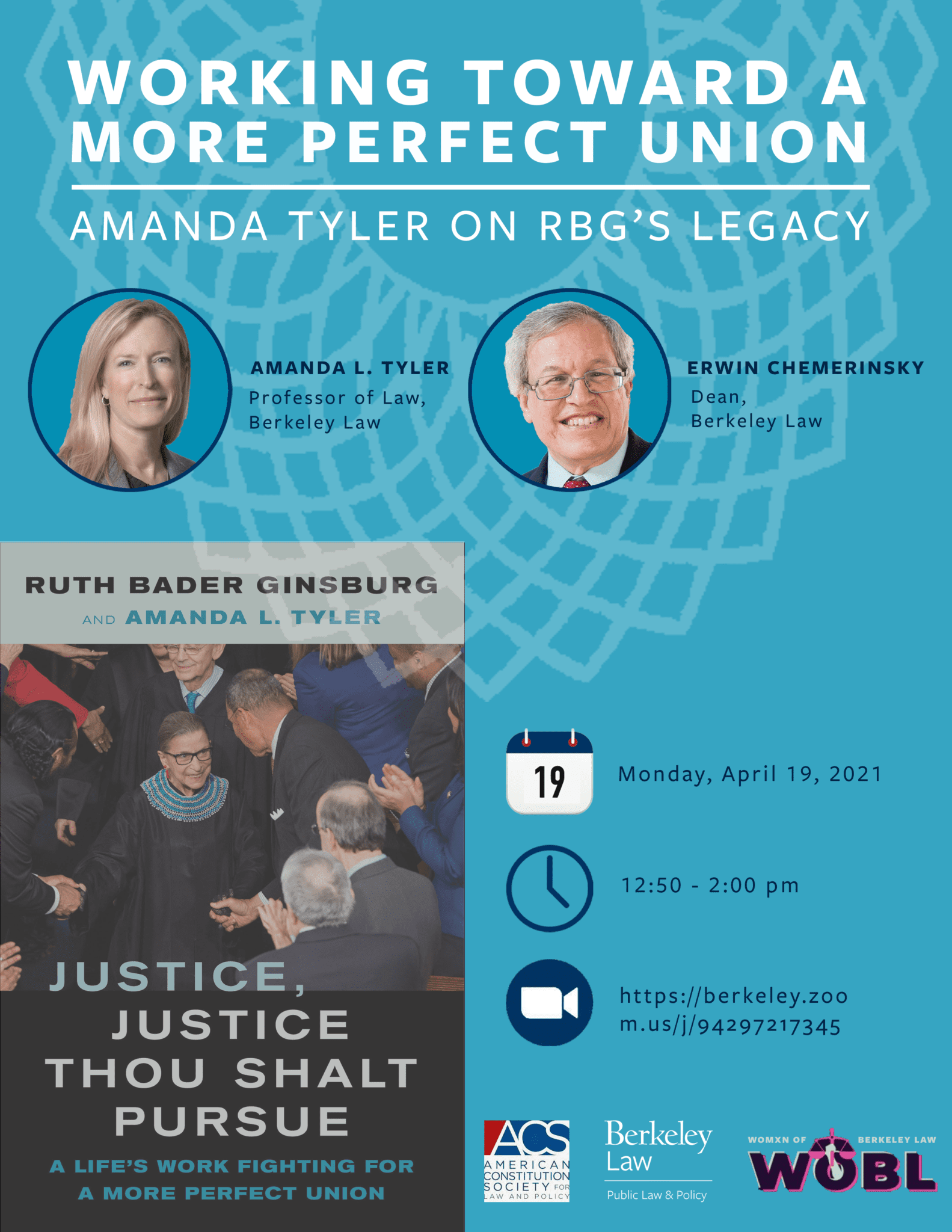

Working Towards a More Perfect Union:

Amanda Tyler on RBG’s Legacy

Monday, April 19, 2021 | 12:50 – 2:00 pm

Zoom | Berkeley Law

Event Video

Event Description

Dean Erwin Chemerinsky leads a discussion with Professor Amanda L. Tyler on RBG’s life and legacy, in concert with the recent publication of Professor Tyler’s new book: Justice, Justice Thou Shalt Pursue: A Life’s Work Fighting for a More Perfect Union, co-authored by the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Panelists

Amanda L. Tyler is the Shannon Cecil Turner Professor of Law at the University of California, Berkeley School of Law. Professor Tyler’s research and teaching interests include the Supreme Court, federal courts, constitutional law, legal history, civil procedure, and statutory interpretation. She is the co-author, with the Honorable Ruth Bader Ginsburg, of Justice, Justice Thou Shalt Pursue: A Life’s Work Fighting for a More Perfect Union, which the University of California Press will publish in early 2021.

Erwin Chemerinsky became the 13th Dean of Berkeley Law on July 1, 2017, when he joined the faculty as the Jesse H. Choper Distinguished Professor of Law. Prior to assuming this position, from 2008-2017, he was the founding Dean and Distinguished Professor of Law, and Raymond Pryke Professor of First Amendment Law, at University of California, Irvine School of Law, with a joint appointment in Political Science. Before that he was the Alston and Bird Professor of Law and Political Science at Duke University from 2004-2008, and from 1983-2004 was a professor at the University of Southern California Law School, including as the Sydney M. Irmas Professor of Public Interest Law, Legal Ethics, and Political Science. He also has taught at DePaul College of Law and UCLA Law School.

Event Flyer

Event Transcript

Erwin Chemerinsky: It’s my enormous pleasure to talk with my colleague, Professor Amanda Tyler about her new book – which you see on the screen – Working Toward a More Perfect Union. And the book’s title is “Justice, Justice Thou Shall Pursue a Life’s Work Fighting For a More Perfect Union,” and it’s a book that Professor Tyler did together with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Ky great guess is that those who are watching this afternoon are very familiar Professor Tyler. She’s Shannon Cecil Turner Professor of Law here at the University of California, Berkeley. She went to Harvard Law School, Stanford College before that. Following law school she clerked for Judge Guido Calabresi on the United States Court of Appeals for the second circuit, then clerked for Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. She worked in private practice, became a law professor at George Washington Law School, and then we were incredibly fortunate to bring her out to Berkeley. She’s one of the leading experts in the country with regard to habeas corpus, before this book wrote an award-winning book on the subject and so many prominent law review articles. And I have the great joy of talking with her about this book. The book is the outgrowth of Justice Ginsburg coming here for the first Hermit Hill

K. Memorial lecture. Professor Tyler arranged for Justice Ginsburg to come and that she and Justice Sinsburg decided that the best format would be an interview. Many of us I’m sure on the call had the great pleasure of watching your terrific interview with Justice Ginsburg, but Amanda I have a different question: what did it feel like to interview Justice Ginsburg? Especially to do so in front of an audience of thousands.

Amanda L. Tyler: I keep thinking back to there’s a wonderful book that my children have both read in school called Wonder, and if you haven’t read it it’s a fabulous book and it’s a very quick read. There’s a scene at the end – it’s also been made into a movie I should say – where Augie gets up to win an award and he has a line in the book where he says, “Everyone once in their life should experience a standing ovation.” So how does that connect? I remember walking on that stage with her and she got a standing ovation and it just took my breath away to feel the intensity of the admiration for her that was in the room and I in that moment I thought about that line in the book wonder and thought, “I know that none of this is for me but wow this is really special it’s really a neat thing.” So that that’s the single most prominent memory of that. And then I think it was just, you know, it was just so much fun. We had done an interview a similar interview years earlier for just my civil procedure large section class at berkeley in 2013 and so we had done this before but we knew going into the event that we were going to turn the conversation into a book so we had had a really extensive back and forth to plot out what we were going to cover and that made it really special because it was really a joint effort of crafting the coverage that would span her whole life in the event and we got to a lot of it. We did not get to everything because at the end I knew we had been going for an hour and I had many more questions, but I also knew she’d been on the stage at that point for I think an hour and a half and I felt like maybe we need to bring this home and I could see looking over her– so we were seated like this and to this side were the us marshals who were her protection detail and so whenever I looked at her I could see them behind and one of them was doing this and so I had to I had to throw it in and and wrap it up. But it was funny because she had several stories that she really wanted to tell and in the interest of time I had skipped over a prompt for one such story and when we were walking off the stage she said, “Darn it I really wanted to tell that one today.” So she was she she knew exactly what we had planned to cover and when I when I did skip that one question in the middle she she was acutely aware, she never missed a beat. But but to be clear she wasn’t being critical of me, she was she did say in the same breath that was really fun and really enjoyable.

Erwin Chemerinsky: How did you and she decide what to focus on? She’s obviously had an amazing life to that point – prominent attorney, leading lawyer for the ACLU Women’s Wife Right which she created, D.C. Circuit Judge, Supreme Court Justice – what did you most want to focus on in the interview?

Amanda L. Tyler: You know it it’s hard and and even if you look at the book there are things that we don’t cover in the book about her life and career and I wish, you know, if if we decided to make it bigger that we would have covered more. But but the same with the conversation we didn’t want to overdo it, we didn’t want to cover absolutely everything, we wanted to craft a conversation that would hit the high points, And hit the high points as she saw them. So give people an idea of how hard it was for her generation of women lawyers to come into the profession, give an idea of how dramatically different the law was when she started advocating in the seventies – particularly with respect to gender equality – give people an idea of what made her tick, what was how she thought of her identity and who she was. So in particular we wanted to talk a lot about Marty because Marty was such a force of a special person in her life, you know, her partner and all things and she loved to talk about Marty and I love to hear her talk about Marty so I wanted to make sure that we had a lot of that. I also wanted to have her talk about her favorite opinions and and prod her to really try and name a few and I knew that we were going to be having this as an ongoing conversation because when we had envisioned going into the event doing a book on the back end, we talked about her picking her favorite opinion so I really wanted to prod her to get her to start thinking about that. The question I didn’t get to that i would have asked next is what are your least favorite decisions from the Supreme Court? What would you most like to see overturned in time? And I wish we had had time to do that, although I think given all the other interviews she’s given in writings she’s done including a speech that we include in the book, I think Citizens United would be high on that list. I think we can certainly count on Shelby County being high on that list – she was very proud of that dissent and we’ll probably talk about that as we go further. But, you know, I keep coming back to I wish that we’d had just a little more time, a little more time to cover some more of this.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Before we talk about her and her writings in the book I want to talk about you and what was it like to work with her as a co-author or even an interviewer having clerked with her about twenty years ago? It’s a very different role.

Amanda L. Tyler: A very different role, yes, but she was still teacher and mentor and I was still in some respects law clerk and I’m super happy about that. I mean, she as a boss twenty years ago was meticulous and set very exacting standards – you worked really hard to try and meet them and what I loved about working for her then and also in the last year was that when you did meet her high standards she was very celebratory of your efforts. So she and she set the most exacting and highest standards for herself. So she never asked any anything of her clerks or of me and working on the book that she didn’t ask of herself. And what was really special about working with her on the book was having this opportunity again to collaborate with her and to learn from her. I will say that I’m not sure that I had come as far as maybe I thought I had in those twenty years which is to say when I used to give her draft opinions they would come back completely covered in ink. I’ve told many students about this, you know, you couldn’t even see the type script on the page and we would give them to her triple spaced so that’s how extensive the comments were and yet twenty years later when I gave her a draft of the introduction, her assistants printed it out for her, she was actually in the hospital marking it up and I said oh I remember I said to them, “I think maybe I’ve graduated to double spacing so I’ve taken the liberty of sending it to you double spaced,” and they wrote back, “Nope she’s gonna want it triple spaced.” Sure enough it came back completely covered with comments and move this and that and add this and and, you know, it was humbling because as I said I thought maybe I’d gotten a little bit further along on the curve of of good legal writing by then but but it also, I mean, I like to talk about that because it shows that right up until the end she was extremely meticulous still and she was still teaching me. She wrote me back a cover email that she dictated in which among many other things she said, “You have a few practices in your writing that I do not adopt and here’s why I think you should reconsider these practices.” So she was very much still teaching me. And the other thing I will say are two things: one the assistants had printed out my cover emails for her on various occasions and she had returned those also edited, which is really embarrassing, but shows again her meticulous attention to detail and that I keep needing to up my game, but the other thing I will say apropos what I was saying earlier is that when she sent things back to me she always made a point of saying, “I really like what you’ve done” and “This is great.” And so she’s someone who really pushed you to be your best version of yourself, but also was very quick to celebrate you when when you succeeded and I’ve tried to model who I am as a mentor and teacher off of off of how she was.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Let me follow up in terms of that aspect – is there particular advice that she gave to you that’s been meaningful to you?

Amanda L. Tyler: How long have you got? She she gave a lot of great advice over the years and it wasn’t always about work. You know, she liked she did talk to us – a lot of her clerks – about work-life balance. She also modeled it and she modeled very much the importance of choosing a partner who valued you and supported you and and and lifted you up and was your your champion, like Marty was to her. But she also gave advice about how to be a good lawyer, how to think about the law, and she taught me so much about that. I do think back in particular to one particular exchange – I don’t know if you would call this advice, but it’s something that I think is really a window into who she was. When I went back to work after having my first child, I’d had a semester leave, and I went back that fall actually as a visiting professor at Harvard and so we moved and and had, you know, I was in a new teaching in a new law school and I remember I wrote her an email and I said, “I’m really nervous. I’m going back to work and it’s a new environment and now work-life balance has taken on a much more consequential element now that I have this helpless child at home.” And she wrote back a very elegant very simple response it was one line and she wrote back, “Where there’s a will there’s a way.” And I love that because I think that’s a window into exactly who she was if you know the about the conversation, if you know anything about her life, you know that from one thing to another, one roblox roadblock excuse me after another was thrown in her path and she just kept moving forward. And I think it was because she had this ferocious determination to contribute and to serve and where there’s a will there’s a way. She had incredible will to propel herself forward and to use her talents to make a contribution. So that I think is probably on, as a general proposition to share with this audience, the best advice she ever gave me which is just put your nose down and do the work.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Let me shift to talking about the book itself. A good deal of the book is your interview with her that’s been edited, some of it is some briefs that she wrote, but I was particularly interested in the choice of cases. And as I remember there are four. One is her majority opinion in United States versusVvirginia and then there are three dissenting opinions: the lead better case about pay equity, Shelby County that you mentioned in terms of the voting rights act, and Burwell versus Hobby Lobby in terms of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act and the obligation of employers write contraceptive coverage for women. I don’t know the total number of opinions she wrote is a DC Circuit Judge in a Supreme Court Justice, but four is a tiny percentage. Why these and why three dissents?

Amanda L. Tyler: So to give you an idea of just how tiny a percentage it is she wrote over seven hundred opinions in thirteen years on the DC Circuit and some four hundred and eighty-three on in twenty-seven years on the Supreme Court. So yes, why these four? It’s a great question. I remember over the summer as we were getting ready to finalize everything and submit it to the publisher, I had been reading up more about her and thinking back, reflecting on the opinions with which i was familiar, and I actually went back to her and

I said, “Boss-” you know I still called her boss, “I think we should we should add a few and I or, you know, consider adding this one or this one.” And she said, “Nope, those are the four, those are the four. Those are my favorites.” So there was something about each of them that I think really spoke to her and I can speak about each of them individually if you’d like, but to your question about the dissents – I don’t think that was an accident. I think that she very consciously wanted to include dissents in order to highlight her frustration with how the court had been in the last period of her tenure there Particularly the fact that she she didn’t– I actually ran the numbers, she didn’t dissent numerically more in the back half of her time on the Supreme Court than she did in the front half, she was dissenting about the same average number of times each term throughout her entire career on the court. But I think she thought the dissents were more consequential and I think she was growing increasingly frustrated with how particularly in areas about which she cared so passionately, about which or on which she had spent her life’s work – reproductive rights, gender equality, voting, and racial justice – she felt like the court was, if anything going backward. And so I think the inclusion of the dissents was, one to highlight this and draw attention to this, and two and you know this was the idea of the book to to inspire people to keep doing the work. We dedicated the book to all those who work to make ours a more perfect union. That was that was the very idea behind the book and here I think what she’s doing is laying out for people: this is where we need to be focusing our efforts and among among many other places, but this is these are battles thatIi think she wanted people to keep waging even after she was gone.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Let me talk about that aspect of her career. The court did become more conservative in her time on the bench. When she went on the five conservatives were Rehnquist, O’connor, Scalia, Kennedy, and Thomas. And Roberts is probably as conservative as Rehnquist, certainly Alito who replaced O’connor is more conservative than O’connor had been. Gorsuch is probably just as conservative as Scalia. Kavanaugh is probably more conservative than Kennedy. And Thomas remains. How did it affect her to realize that the court around her was becoming much more conservative?

Amanda L. Tyler: I think she she did not like to lose. Who does? But I she really some of these cases I think back particularly to Shelby County. She came to visit Berkeley the first time while I was on the faculty right after the fall after Shelby County – I think it was September after that decision had come down – and I remember a line that she she spoke in her speech and I think it’s in the bench statement as well. She said: “What has become of this court’s restraint?” You know what is all this talk about judicial restraint. Here in the voting rights act, congress was acting pursuant to its constitutionally vested enforcement power and the Fifteenth Amendment and were second guessing their work in the face of this massive, massive legislative record, in the face of legislation that President Bush signed, that passed unanimously in the senate, and now the court is coming in and saying congress has overstepped. So I think she grew really frustrated with – particularly in that context – a lack of deference to the legislative process and she felt like in some respects the criticism that had or that had primarily been lobbed on liberals, this so-called judicial activism that maybe, you know, it was a criticism that could be turned around. And that’s a case in particular where I think she really took umbrage to what the court was doing and she felt like it was bringing us backward, we were walking back the gains of the Civil Rights Movement and particularly this enormously important piece of legislation in the Voting Rights Act. But she also, I think she really became frustrated and this comes through in the lead better descent with particularly in that period where she was the only woman on the Supreme Court after Justice O’connor retired, she talked a lot about and she did this publicly not just to me and others. She did not like being the only woman on the court. And you see that frustration come out in the lead better dissent because you there have an all-male majority saying, you know, really dismissing ongoing systemic gender-based pay discrimination and she’s she’s you read the dissent it’s it’s really I mean I’m biased but I think it’s magnificent because she’s walking them through trying trying so hard to explain to the majority: this is what it’s like to be the only woman in a workplace and this is how, even if you find out you need to understand that even if you find out that you’re the victim of pay discrimination, you’re not immediately going to complain because you’re going to be labeled a troublemaker. You’re going to think very carefully about how to go forward, you’re going to make sure you have an ironclad complaint. And they just were so far removed from the that experience, one that she had been through herself personally, that you really do get to see some of that frustration come out. But it was always always respectful. I mean she used strong language in a lot of those descents, but it was always respectful. She she was always engaging with the ideas and never attacked individuals on the court.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Let me then ask a more difficult question: in March 2014 I wrote an op-ed in the LA Times saying Justice Ginsburg should retire this summer. I said the Democrats have the White House in the senate. Every prediction was they were going to lose the senate November 2014 they did. So no one could know what’s going to happen in November 2016 which was certainly an understatement. I said if she wants somebody with her values and views to take her place, now is the time to step down. She reacted quite negatively to that, including identifying me by name as somebody who had suggested this, and made very clear she wasn’t going to go anywhere. But if she cared so much about all of these things, shouldn’t she have stepped down then? Of course what ended up happening is she didn’t and we have Amy Coney Barrett taking her place and hard to imagine somebody with different ideology or am I being very unfair?

Amanda L. Tyler: I think it’s it’s hard, right? Hindsight is is 2020. Everybody knows that expression. What I can say is that in that time and particularly the time you identify when you published your op-ed, I talked to her about this so many of her clerks did and she spoke publicly about this and what she said was, “I love this job and I’m going full steam and I feel like I have contributions to make and as long as I do I want to keep doing this job.” And I realized that in retrospect we might have done have had her make different decisions, but what I think that shows and the person that I knew was that there was this deep devotion to service. And it wasn’t it wasn’t just that she loved the job – which she did – it was that she was deeply devoted to the role and the service or service aspect of it. Serving her country. She loved this country so much this country, she talks about this in the book that gave refuge to her family fleeing persecution in Europe, she absolutely loved this country and loved all that it could be. She talks about this in the book, as I said. She also talks about what makes our country so special is not that we’re somehow more enlightened, but that we have the ability to look at our faults and repair them, which is a pretty timely message right now. And I think when you when you understand who she was and you understand how much she loved the country and you understand that this was a life of, again, where one roadblock after another was put in front of her but she was just so determined to make a contribution that I think it was really hard for her to hang up and walk away and not be that public servant anymore. And so again I don’t think the criticism is necessarily completely unfair, we know how the story has played out, but I think in real time she she was driven to serve and and if you’re built that way, it’s really hard to walk away.

Erwin Chemerinsky: I want to talk a little about what caused her to be so driven to serve and what influenced her. You’ve already talked about the role of gender for her – one of the few women in her first year law school class at Harvard, being the head of the ACLU Women’s Rights Project, three of the four cases you chose in terms of her opinions on the Supreme Court involve gender, The United states vs Virginia Ledbetter, Hobby Lobby – let’s talk about some of the other influences. One is about being Jewish. The title of your book, “Justice, Justice Thou Shall Pursue” comes from language in the Torah. In fact you can’t see the wall behind me in my house, but the wall has two different frame things there, both of which say, “Justice, Justice Thou Shall Pursue.” If you come to my office at the law school, when we’re all allowed to go in the building again I have a lithograph that has the words in Hebrew English of this. I was very interested to see a couple of the essays which I’d never read before that also linked to this. Can you talk about that aspect of her background, how it influenced her as a person as a judge?

Amanda L. Tyler: Yes and as I discuss in the in the book, the title comes in part from the fact that she too had artwork displaying, “Justice, Justice Thou Shalt Pursue” up in the walls of her chambers. And a number of us law clerks, after she passed away, we all were reflecting on how as we think of it that is that is how we describe her her core principles and and what drove her. I think being Jewish was a huge part of her identity. She talks in the book through various speeches about first, as I mentioned before, how grateful she was to this country to open its doors to her her father and and and her grandparents, her mother was born only immediately after they arrived in this country, and they all came fleeing the horrible developments in Europe. And they found refuge here and this country took them in. And she was very, very proud not just to be Jewish but also to be the child of immigrants. And the final the final installment in the book is a is a excuse me a speech she gave at a naturalization ceremony in which she welcomes all of these immigrants as new full citizens of the United States and she says to them, “This constitution is yours now as much as it is mine and it and it’s up to you just as much as me to do the work to make our country live up to the highest principles to which we aspire.” But she also included a speech in which she talked about as a girl having these incredible Jewish female role models and it connects back to everything I’ve been saying – Emma Lazarus, you know welcoming, all these new faces in the form of immigrants to join our society and and and, you know, be a part of the American fabric. She talks really magnificently about Anne Frank and many of us everyone as a child in this country at least I hope this is still the case reads that diary growing up. I know my kids have read it. I didn’t remember there being as much in there about gender equality but there are passages in there about gender equality and she highlights those and says, you know, these were a really powerful influence on me and I think that’s really magnificent. So it shows that a lot of her core values were very much woven in with her faith and her family and her family’s story and connection to this country and I think that’s a big part, again, of what drove her to you know. She told my students when she came to berkeley in 2013, I remember she said, “If you have the talents and the gifts to be at a place like Berkeley Law, you have a lot to give back and it’s up to you to use those talents and those gifts to do something to give back and to make life better for others especially those who are not as fortunate as you.” And and I think that’s where all that drive came from on her part.

Erwin Chemerinsky: I think I mentioned to you when we were talking about the possible title for the book that I had heard a rabbi give a sermon about why does the torah say, “Justice, Justice” repeating the word. And though the rabbi didn’t know the phrases “procedural due process” and “substantive due process,” that was exactly what her answer was. She said would it have justice there has to be fairness of procedures but also just outcomes. And that resonated with me, and of course when you think about her opinions, they’re both about the fairness of the procedures when the government treats people and the need for just outcomes. Let me ask you another hard question: there’s been some criticism of her with regard to racial issues and when I first heard this I was surprised because I went through in my mind her decisions about race and I couldn’t think of anywhere I would say she would not have been on the side of racial justice, but I think it’s important to talk about this. What do you see as a record with regard to race and why do you think this criticism is emerging?

Amanda L. Tyler: That’s a really interesting question and I’m glad to talk with you about it and I’d also would love to hear your thoughts. She, as I look back at it, has a pretty remarkable record on on race and related issues and i think part of it has to do perhaps with people not being fully familiar with both her work as an advocate and her work as a justice – as a judge and justice. So let’s break those up let’s start with her time as an advocate: this is someone who in some of her very earliest litigation for the women’s rights project actually went to the south and filed lawsuits challenging for sterilizations of predominantly women of color who were being sterilized sometimes without their knowledge and other times as a condition of receiving benefits – state benefits – and actually she did that work with none other than Gloria Steinem. They actually worked together on those cases and they they were enormously important cases to her she also is and. And they helped, I want to emphasize why I mention them, they helped her see the ways in which both race discrimination and gender discrimination work together and if anything exacerbate the discrimination on both scores. So what today we call intersectionality among other things. She also, as a litigant before the Supreme Court, filed a brief in the Coker Case – Coker versus Georgia – which is the case in which the Supreme Court held that the death penalty should be off the table as a penalty for rape. And you would think that someone who was thinking solely about women’s rights might possibly support the death penalty as a penalty for rape. She did not she filed a brief in which she said: “This is a very problematic sentence in this context because of the way in which it is often wrapped up with issues of race,” and in particular she said, you know, “If you look at the statistics, we see this penalty being handed down primarily in cases with white victims and black defendants.” And for that reason she opposed the death penalty in that context. So again the work involved work on multiple fronts and an appreciation about how race and gender discrimination often go hand in hand. When you look at her time on the bench what you see is a long record, I think, of understanding and calling out racial discrimination and saying we need to do better. So Shelby county, we’ve discussed, I can say more about that. I think that’s a crucially important decision in her legacy in which she says to the majority, “Look you’re living in a fantasy world, basically, if you think that racial discrimination is still not alive and well in certain covered jurisdictions with long with long histories of racial discrimination and voting practices and that’s why we have the pre-clearance procedures in those jurisdictions under the Voting Rights Act, it’s why we still need them.” And I think history unfortunately has shown us especially lately just how true those words were just think about what’s going on in Georgia right now. She wrote she joined the court in supporting affirmative action in a number of cases and in Grutter versus Bollinger, for example, she wrote separately in 2003 to say we still have a ton of work to do. She supported the the use of affirmative action at the University of Michigan and she said not just that we’re dealing with unconscious racial bias but we still have a country in which express racial discrimination is still far too prevalent and we again we have a lot of work to do. I think about her work in the criminal justice arena, among other things, she is one of I think maybe the only justice who joined – you can correct Erwin, you would know this – Justice Breyer’s opinion in Glossip versus Gross in which she called for an end to the death penalty. She was on the right side of a long list of Fourth Amendment cases with massive racial overtones, and I know you can talk more about this and I’m going to prompt you to do so. But I think about a case the year I clerked Illinois versus Ward Law and that case involved the question of whether if you see a cop and you sort of flee the other direction is that suspicious enough behavior to warrant a stop?

Erwin Chemerinsky: Literally walking on the sidewalk.

Amanda L. Tyler: Literally walking on the sidewalk.

Erwin Chemerinsky: And the guy thought I would see the police decided to walk the other way and the supreme court said that was enough for reasonable suspicion.

Yes.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Because I think it’d be quite wise for someone – especially young men of color – to walk the other way if they see the police coming.

Amanda L. Tyler: Exactly and that point was made I can tell you both inside and outside the court at the time and I’m very proud that she dissented in that case and and joined the dissent and saying, “This is a this is a very dangerous decision in terms of what it empowers police to do” and we of course know that that has played out just as unfortunately they predicted. She dissented in Utah versus Street – similar issues. She did not join every aspect of Justice Sotomayor’s decision, but you and I have talked about this and maybe you could say a word as to why maybe she didn’t join the final part of it. She wrote in Wesby – a decision in 2018 and and I want you to talk about this as well when I wrap up – she she talked about how important it is for us to go back and think about revisiting police accountability. She said our law is not sufficient in holding police accountable for when they abuse individual rights. I could go on and on – she was in dissent on in a number of prominent 9/11 cases: Padilla and Iqbal that involve obviously issues of race and religious discrimination. She I yeah I could keep going, but I think the the lesson is that this is someone who tried very hard to understand what it was like and and and knew from a different set of experiences what it was like to be the victim of discrimination and she, above all things, I think looked at the law as a vehicle for trying to open up opportunities and trying to create opportunities for every individual no matter their race, their creed, their their religion, their gender to be able to have an equal shot. So I’d love to hear your your reflections on on everything I’ve said and particularly on the Fourth Amendment context.

Erwin Chemerinsky: You mentioned some cases by name that people may not be familiar with and I especially want to focus on the Utah versus Street case that you mentioned. What involved was a police officer stopping somebody unquestionably illegally. No one tried to defend the legality of the stop and once the officer stopped the individual, the officer to check to see if there’s an outstanding warrant – there’s an old warrant like a traffic ticket – and based on that the police officer arrests the individual, does a search instantly arrest, and finds drugs. And the question is well since it was an illegal stop, should the drugs be excluded? And the Supreme Court five to three says that the drugs can come in. Justice Thomas writes the opinion for the court. Justice Sotomayor writes a very forceful dissent explaining why this is undesirable in terms of Fourth Amendment doctrine. And then the last part of justice center’s dissent is a very personal one written about race in society, mentioning the talk that parents of color have to give to their children about how to interact with the police, talking about how people of color are treated by the police is in just Sotomayor’s words “the canary in the coal mine.” And I after we talked over the weekend went online to see what I could learn about the criticism of Justice Ginsburg in one criticism is her not joining the last part of the Sotomayor descent. I have to say when it came down I thought it was because Justice Sotomayor was writing very personally as a woman of color and Justice Ginsburg and Justice Kagan who dissented might have thought it presumptuous to join that part of the descent, not that they disagreed with it but wanting to be respectful of the unique experiences that Sotomayor had. But it is an aspect of criticism. You mentioned District Columbia versus Westby. The reason that’s important is one decision where i would criticize Justice Ginsburg for going along with the majority was a 1996 Supreme Court case Ren versus United States, it involved some undercover D.C. police officers who saw somebody stop at a traffic stop sign for a bit too long – twenty to twenty-five seconds. They decided to follow the driver even though they’re not supposed to enforce traffic laws when they saw the driver change lanes without a signal without a turn signal pull the driver over do the search and found drugs. The traffic stop was clearly protectul. This was African-Americans being stopped by the police who weren’t even supposed to enforce traffic laws and the Supreme Court in opinion by justice Scalia said the police motivation doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter if it’s protectional or not, so long as there’s probable cause that a traffic laws violated that’s enough. This decision so opened the door to even greater racial profiling It was unanimous and I’ve never understood why the liberals on the court at the time like Justice Ginsburg didn’t dissent. But in district of Columbia versus Westby just a few years ago she wrote an opinion saying it’s time to rethink that decision – the first justice to do that.

Amanda L. Tyler: Yeah I think that sorry–

Erwin Chemerinsky: No you please.

Amanda L. Tyler: I was gonna say I think that’s a really important component to thinking about her and also assessing her legacy. I would add two more things and then come back to this point I’m, you know, I’m thinking also about her support for Dreamers, her joining the descent and the travel ban cases, there are a lot more of examples of many examples we could cite to show where I think she’s been on the right side of things. But as you highlight, maybe not always, but she does it she did reassess and so your story about the the opinion in Wesby, I think, is a really important story in that regard. And I know she’s also been subject in some cases fairly for to criticism for some of her opinions in the Native American rights area, but her final vote in that area was in Mcgirt and that is a very important decision upholding tribal sovereignty from last term and I absolutely celebrate where she was in that case. So I think i think maybe the criticism is, I would like to say i will say I think it’s unfair. I think actually when you look at the whole arc of the record it’s it’s quite it’s quite wonderful.

Erwin Chemerinsky: I have a few more questions and i do want to be sure and get the chance to everybody who’s watching to ask questions. Is there a story about your relationship with her, your experience with her that you haven’t gotten to tell? Bbecause I know you’ve talked a lot of venues about this wonderful book, but is there some story that you haven’t yet gotten to tell that we get to hear?

Amanda L. Tyler: Yes there’s a great story that I’d love to tell that i wouldn’t tell it in most venues but I’ll tell it here because I probably have a number of students on the on the call. I mentioned a couple of times now that she came in 2013 and that the lead up to that is funny but then what happened is funny as well. So she kept writing me these letters saying, you know, there’s a there’s an opera opening and i might be coming to San Francisco in the fall and I would write back, “Oh that’s wonderful I hope to see you.” And then i went to D.C. for something and I saw her in person and I remember she put her hand on my arm and she said, “Amanda how how direct do I have to be? I would love to come and do something with you at Berkeley while i’m out there.” And I said, “Okay okay I don’t like to ask you to do stuff too often so we’ll make it happen this is great.” So she did come and we as I said I interviewed her before my class and I have wonderful stories about that and her interactions with my students which were just fantastic and then she did a big event where she gave a speech and she primarily talked about Shelby County and how angry she was about what the court had done in that case and then we had a small dinner at the house. The day before all of this the U.S. Marshals who, of course, do all the logistics and protection of her they had come to the house and they had wanted to do their typical walk through and to talk through with me how the next day was going to unfold. And my kids were home and I think if I’m remembering correctly they were pretty young. They were about four and six at the time and I had to explain to them who the marshals were when I introduced them. And I said, I remember I said to them, “Now they you need to understand they take care of all the judges and the justices on the Supreme Court. They take care of really important people.” And my kids said, “Oh that’s that’s great.” You know so the next day we have the event and then the next day at breakfast my kids said to me, my son in particular the older who was probably about six he said, “Mom what was your favorite part about yesterday?” And you have to think okay what am I gonna say to my six-year-old? So I – and that and this is actually true this was one of my favorite parts -I said, “Well honey, after the Justice gave her speech there were two cars of marshals and I got to ride with the marshals in the front car to help them direct to help direct them to our house and we got they they turned on the siren.” Which for anybody who lives in Berkeley and and who is in and around the university campus, you can understand how awesome it was to be in a car with a siren on which meant all the pedestrians for the first and only time in my life had to stop and not cross and make me wait at a stop sign for ten minutes. Okay that’s not the best part of the story. So I’m explaining all of this to my son and I say, “You know I got we we turned on the siren,” and I’m looking at my son and you can see the little wheels in his head are turning and turning and he says, “Mommy I don’t understand. Why were you riding with the marshals? You aren’t important.”

Erwin Chemerinsky: Our children will keep us humble.

Yes they do.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Just a couple more questions, then we take audience and if there’s not a lot of audience questions, I have lots more i can ask.

Amanda L. Tyler: Well I have some for you too.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Okay that sounds fair. The Supreme court is even more conservative now than it was when she went on in 1993 or then she passed away on September 18th. It’s easy for progressive students to be discouraged as they look at a court that’s this conservative, I mean just focus on Amy Coney Barrett. She was forty years old when she was confirmed. If she stays on the court until she’s eighty-seven – the age was just Ginsberg passed away – Barrett will be a justice since the year 2059. What would Justice Ginsburg say to our progressive students in light of all of this?

Amanda L. Tyler: I think she would say, “Put your nose down and do the work.” So what do I mean by that? The year when I clerked for her, although this is during a different time as you described Kennedy and O’connor were the swing votes in 1999 to 2000 it was a very different court, we were on the losing end of a lot of cases. That was a that was a case with a number of very high profile constitutional law cases. I’m thinking for example about the Boy Scouts case that involved the question whether the Boy Scouts could kick out a scout leader solely because he was gay. Lots of other lots of other cases, a lot of abortion cases. There were a lot of high stakes cases and she like in the Boy Scout case, for example, she was on the losing end of a lot of them and she would say to her clerks – we would be so upset. I remember that case in particular I was so upset and she said, “Well let’s let’s move on to the next case because that’s what you do you just keep doing the work. “And I think about two other things, three other things. I think about the VMI decision which was really her crown jewel. This is the case in which she got to write for the court and say women deserve all the same opportunities as men and so that means that the commonwealth of Virginia must open the doors to VMI, to female cadets. And she says look I don’t think I would want to go there but there are women who who want to and can hold their own and they should be allowed to do that. She was very very proud of that decision. What a lot of people don’t know is one of the reasons that decision was so special to her is that she, in the seventies, had been a part of a case that went to the supreme court that raised the very same issues and that they lost. So that case was called Vorthymer and it was a challenge to two high schools for high achieving kids in Philadelphia. And one was for boys and one was for girls. And a girl wanted to go to the boys school because guess what? It had better classes, better facilities, better opportunities, etc. And so she sued and the case gets to the Supreme Court after the district court ruled in favor of the girl, the third circuit reversed so they said, “No the separate schools are fine, they don’t violate the Equal Protection Clause.” The case goes to the Supreme Court and at that point Justice Ginsburg and the ACLU get involved and she was the primary author of the opening brief, but she had a very different theory of how to litigate the case that was in keeping with the other cases she had litigated before the court – most of which she’s winning during this period we need to emphasize. Local council wanted to litigate it on a different theory that was an outgrowth of the theory that succeeded in Brown and there developed the schism between the two camps and local council basically pushed out, the ACLU wrote the reply brief herself and argued the case herself. And the court split four to four which meant it affirmed the third circuit decision. So it’s almost twenty years between Vorzheimer and VMI and I think what made that decision so sweet was that finally at long last she got to reverse Vortimer and that’s an important component to thinking about her legacy and what kind of lessons I think she would talk about in this moment. She would say it may not happen overnight – what you’re trying to achieve – but you’ve got to put your nose down, you’ve got to do the work, and you’ve got to stay the course because you can succeed over time. The other thing I think she would say is don’t just think about the courts. When she was at the Women’s Rights Project, they were very active in pursuing legislative victories as well even where the court wasn’t amenable to their arguments. So in in general they they supported Title IX – huge watershed legislation that has benefited benefited excuse me generations of individuals since then – and they supported the pregnancy discrimination act. Having twice seen the Supreme Court reject the proposition that pregnancy discrimination is gender discrimination. So they went to congress and they got it through congress and congress agreed and amended Title VII to that effect. So another lesson she would say is don’t just look to the courts. And finally, I think putting all this together she would say look at how far we’ve come. Yes we have so much further to go but she often talked about how much change she had seen over the course of her life, particularly with respect to race and gender and again going back to that quote from De Tocqueville, she would say again what makes our country so special is that we can study our faults and we can fix them. And so you just have to stay the course, you have to keep doing the work, and we’ll get there. I think that’s what she would say.

Erwin Chemerinsky: I want to say a question, but you said you had something you wanted to ask me.

Amanda L. Tyler: I want to – thank you – I wanted to ask you what it’s what it was like to argue in front of her because I know you did many times and I never had that privilege.

Erwin Chemerinsky: I did. I knew that she would always ask questions. I knew her questions would always be probing. The first case that i argued in front of her was a case called Lockyer versus Andrade in which I was representing a man who’ve been sentenced to life in prison with no possibility of parole for fifty years was doing one hundred and fifty dollars of videotapes from Kmart stores. He had received this sentence under California’s Three Strikes Law, even though he never committed a violent crime even though prior to California’s Law no one in the history of the United States had ever received a life sentence for shoplifting. And what took me by surprise was that the most aggressive questions came from Justice Ginsburg. I expected going in that Justice Ginsburg would be solidly on my side and indeed she did vote on my side, but she was the one who asked the questions that I think were going to be in the minds of the conservative justices and wanted me to have the chance to respond to them. And as I got to watch her pattern of question, this wasn’t a typical for her. She was really helping me by giving me the chance to address what would be most in the conservative justice line. I lost five to four the, though Justice Ginsburg was in dissent. The other is much more of a personal anecdote: I happen to have two Supreme Court arguments in the same month of March 2005 and right before the first, I developed a severe ear infection and completely lost hearing in one ear and it was the side of the bench that Justice Ginsburg sat on at that time. As you know sometimes an oral argument she spoke softly – in fairness sometimes it seemed like she was even mumbling – and I was so afraid at the oral arguments she was going to ask me questions that I just wasn’t going to be able to hear and be in the embarrassing position of saying, “Justice Ginsburg can you repeat that question?” And I literally spent time practicing of how to shift my body so that I could use the ear that I was hearing from to be able to hear her questions. And thankfully I was able to hear her questions. I got her vote in both cases – I won one seven to two and lost the other five to four.

Amanda L. Tyler: That’s a pretty good track record.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Well if yeah for those two cases, not if you look overall. But, you know, she was a lawyer’s dream in the sense that her questions were always the ones that really needed to be asked and she asked precisely. There I mean justice Breyer was always for me the most frustrating justice because he would ask these long rambling questions. He sort of put his chin in his palm and he asked this question and I’m watching the clock ticking down, okay just ask the question already. Justice Ginsburg, the questions were always much more exact and always very probing.

Amanda L. Tyler: That’s great.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Well let me see if we’ve got some questions and if not I’ve got a lot more to ask you. There’s one here that says: Professor Tyler has been interviewed by a fascinating group people about this book. What do you find people most want to know about RBG?

Amanda L. Tyler: That’s a great question. It really depends on the audience, to be honest. I think there is a huge amount of interest in her marriage and her partnership with Marty, which is a favorite topic for me and all of the clerks who knew him to discuss because they were, it was a love affair for the ages, it was just such a privilege to watch those two interact. And particularly the year when i clerked for her was the year she had her first bout with cancer and he was so doting and so wonderful to her. He would come and usher her home say, “You’re working too late” and he made all special meals for her to help her keep her weight up. He was he was just an extraordinary human being and their partnership was a partnership in the truest sense of the word. Another thing that a lot of people a lot of people have asked me about is her friendship with Justice Scalia and there’s a lot of interest in how were they able to to have a friendship and what I’ve said about that from what I observed is that – and from what they said publicly – is that they had a lot in common and they built their friendship around what they had in common. And they also they they took each other’s views seriously she gave a speech at his memorial and I have to say I regret actually not suggesting that we included in the book because I think it’s an important speech. She talks there about their friendship and she says that in giving her an advanced copy of his dissent, he was the only dissenter I should note, in VMI it allowed her the opportunity to go back and refine her own arguments in her majority opinion. And she says the end result was an opinion that was so much better than the first draft and I think that’s a really important lesson for lawyers. It transcends the law, obviously, but to be a successful lawyer, you really do need to understand the arguments on the other side and explain them away you have to engage with them. And one of the things that they did in their friendship and the VMI story is emblematic of that is they would engage with each other and very rarely agree. Very rarely agree I can think of a few occasions that come to mind in in close cases. I mean obviously on balance they agreed the court hands down a lot of you know unanimous opinions, excuse me, but in the high profile cases there’s rare agreement between them. So but I think that’s a really important thing to keep in mind. So those are two of the questions I get the most actually I think.

Erwin Chemerinsky: I’m going to ask a question before I go to the audience. Is there a question you wish you were going to ask that you don’t get asked?

Amanda L. Tyler: Is there a question I wish that would be asked of me?

Erwin Chemerinsky: With regard to the book. I mean as I was thinking about the question of, you know, what are the questions you most get. I’m curious if there’s a question you think you should be getting or wish you were getting that people aren’t asking.

Amanda L. Tyler: I’ve gotten it a few times but I do welcome the opportunity to talk about this. I’d love for people to know – and I talked about this at the prior Berkeley event – about the story of the origins of the book. We as we were working on our conversation we were thinking that we might want to do something bigger with it and then we learned that UC Press was considering publishing Herma Hill Kay’s book and they had previously turned it down as had another publisher and that book chronicles the lives of the first American women law professors it’s called paving the way and it’s over my shoulder next to our book. Justice Ginsburg so wanted that book to be published, she thought it was so important to chronicle and preserve the stories of women who had broken down barriers for her benefit and for Herma’s benefit and she had been friends with Herma forever – they had written that first case book on sex discrimination and the law together. So we got the idea that we would in fact move forward and do a book project and we only ever offered it to UC Press and we did so saying we want this book to be to come out alongside Herma’s book, that would make us very proud and it would be very special particularly for Justice Ginsburg. And so I love to talk about that because it’s a window also into how selfless she was, how she used her position to lift up the voices of others, and how loyal she was as a friend.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Let me read you another question. It says: how did Justice Ginsburg make sure to remain in touch with or keenly aware of the people whose lives were greatly impacted by your opinions even after so many years on the bench?

Amanda L. Tyler: This is a great question this. This past week the Columbia Law review published a tribute issue they devoted an entire issue to honoring Justice Ginsburg, who was one of their editors many many years ago when she transferred to Columbia from Harvard to do her third year, and they included an essay written by Stephen Weisenfeld who was one of her all-time favorite clients. And it’s just a magnificent window also into who she was as a person. She was incredibly kind and here’s someone who lost his wife and childbirth and wanted to stay home and raise his son and this was. in her mind this, this is exactly what she wanted in terms of gender equality – for both parents of where they are of different genders to both equally share the parenting and she always talked about this is one of the most important, if not the most, important factors to women’s equality. And here’s a dad who wanted to stay home and the law discriminated against him by giving him lesser benefits than his wife would have received. And she didn’t just win that case, she took it on from the beginning – which is important – from the outset she took him all the way to the Supreme Court and and prevailed, finally got Justice Rehnquist then Justice Rehnquist’s vote in a gender discrimination case which made her very happy. Although he was predominantly concerned with the interests of the child as opposed to the gender inequities between the mother and father and their respective benefits, but she kept up with them. She kept up with them. She very proudly celebrated when Jason that – the then baby – grows up and goes to Columbia Law School. She married Stephen Weisenfeld when many years later he remarried and she kept in touch with him throughout. So her clients were not these abs this is – the same way she thought about cases from the aspect of being a judge. The people who were being affected by these cases and and these decisions, they were not abstract to her they were real human beings and where she had a direct personal connection I can say this from my own experience and relationship with her, she invested her whole self in those relationships and and did so for life and there are so many of us who are so incredibly grateful for that because having her in my life – I’ve said this before – she was like a north star she was so special and and just what a privilege it was to know her.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Another question came: would you share another favorite memory of Justice Ginsburg?

Amanda L. Tyler: Oh there are so many. One I love to talk about was is going to the opera with her because she was – as you’ve described her – when she was often soft-spoken, she was very meticulous not just in her writing but in her her oral presentations, reading opinions from the bench, and asking questions from the bench, and even everyday conversation. But when she talked about or went to opera, she really morphed into another another human being. And I remember when i was her law clerk she took us to Sitoska and and she had arranged for us to go in the middle of the day which was great, right? Iit was you show up for work and you go to the opera it was wonderful. But she knew that many of us were among the clerk group were not familiar with the opera so the day before she had us into her office and she had a round table and I think you know that was that was symbolic, she liked people everyone was equal at that table there was no head of the table and and she talked with us and described to us the story of Tosca and if anyone’s seen it or if you haven’t in the final scene, Tosca is crawling along the stage and Justice Ginsburg got up out of her chair and she started acting this out and she’s just just morphed into this totally different personality that was larger than life and and I love that about her and and then I remember I went to see the barber of seville with her – I think this was the year after I clerked with her – and Marty was traveling and she said oh would you like to come and I said yes. And she insisted that I sit in front of her, they had a box and they had the seat once the seat was slightly in front of the other seat. So she said you sit there, you haven’t seen this production and every single song she would put her hands on my shoulders and she would grab them and she would – and she was really strong I don’t think people realize how strong she was she. This is a period when she was working out with her trainer and she was doing one arm push-ups which I’ve never been able to do and I was a college athlete but in any event she every single song she would whisper in my ear, “This is my favorite song!” with just huge enthusiasm. She just loved the opera, she absolutely loved the opera and it brought her such joy and it was just it was really fun to see her in that environment and and see that part of her personality that you didn’t often see otherwise.

Erwin Chemerinsky: We’re almost out of time. I have one last question, which I realize is an unfair question but I’m going to ask it anyway: we’re now about six months after she passed away, if you think twenty, thirty, fifty years from now what do you think her legacy is going to be?

Amanda L. Tyler: I’d love to hear your thoughts on this too or when if possible. I hope that her legacy is one of service first and foremost. One of using one’s talents to try and make the world a better place for others in a very selfless way. I hope that her legacy is one that inspires people to do the same – to use their talents to fight for what they believe in and not to back down and to stay the course. And I hope substantively her legacy is remembered as one that promoted this idea that we can do better, we have the tools to do better, we are ever evolving and improving, and we need to ever evolve and approve improve. We need to self-assess, see where we can do better, and then do the work to get us there, and through all of it to do our part to open up opportunities. This is this is something she talked about time and again and I think it was central to who she was and how she thought about the law. Do our part to open up opportunities for everyone to be able to chart their own destinies and create their own happy lives.

Erwin Chemerinsky: What a wonderful legacy. What a terrific answer. We’re out of time now. I just want to thank you, Amanda, for doing this terrific book with Justice Ginsburg and for taking the time now and letting me ask you the hard questions as well as the easy ones and I want to thank everybody who tuned into this and if you haven’t done so, it’s “Justice, Justice Thou Shall Pursue a Life’s Work Fighting for More Perfect Union” by Rruth Bader Ginsburg and Amanda Tyler. You should get it. Thank you.