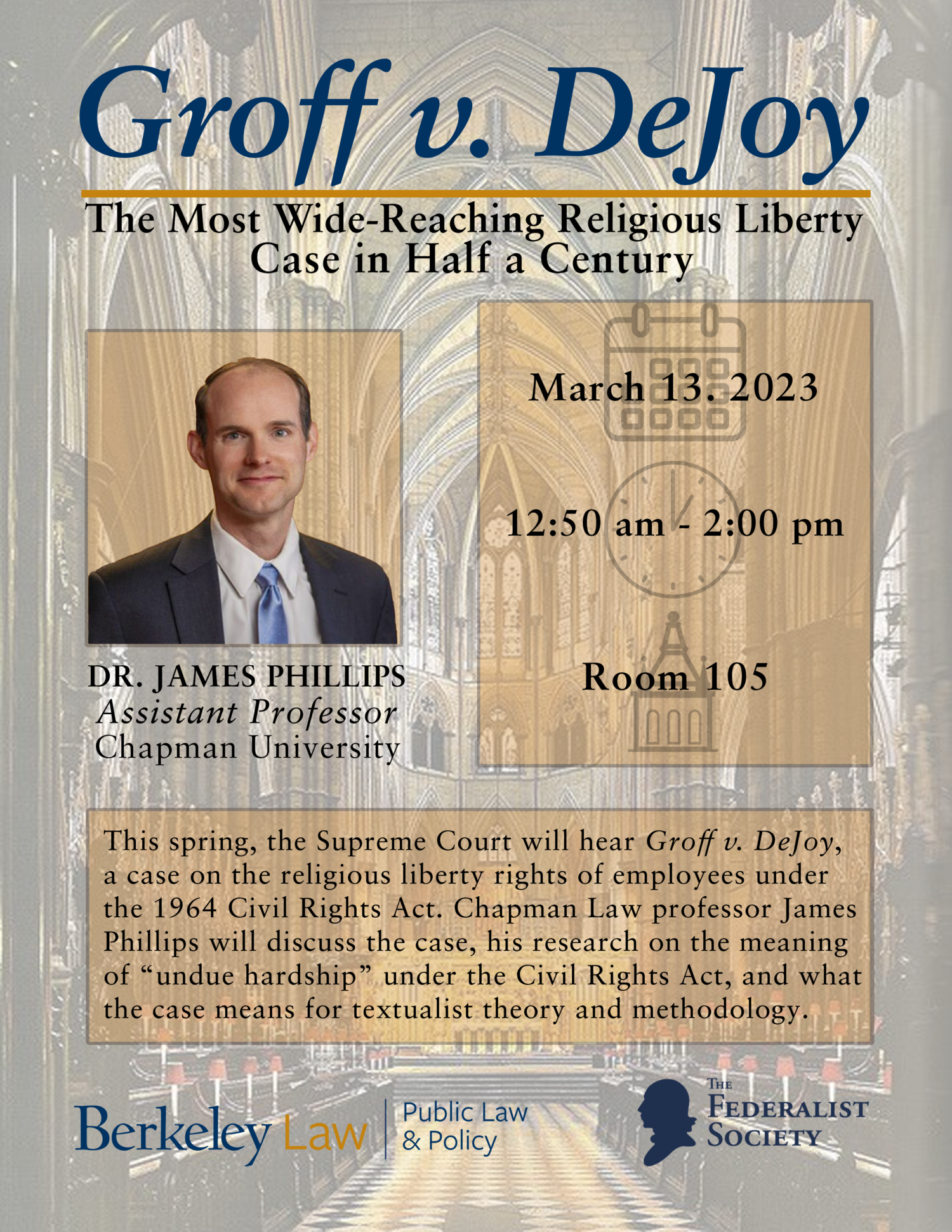

Groff v. DeJoy: The Most Wide-Reaching Religious Liberty Case in Half a Century

Monday, March 13, 2023 | Room 105, Berkeley Law

Event Video

Event Description

As the Supreme Court considers Groff v. DeJoy, a case on the religious liberty rights of employees under the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Chapman Law professor James Phillips discusses the case, his research on the meaning of “undue hardship” under the Civil Rights Act, and what the case means for textualist theory and methodology. Professor John Yoo provides commentary.

Panelists

James Phillips is an assistant professor of law at Chapman University’s Fowler School of Law where he teaches courses in civil procedure and law and religion. James has published over two dozen academic articles in journals such as the University of Pennsylvania Law Review, Southern California Law Review, the Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy, and the Journal of Supreme Court History. His research topics include constitutional interpretation, law and corpus linguistics, the First Amendment, Supreme Court oral argument, and empirical studies examining discrimination. He designed and supervised the initial stages of the creation of the Corpus of Founding-Era American English (COFEA) and is one of the pioneers of applying corpus linguistics to constitutional interpretation. His shorter writing has appeared in The Atlantic, the LA Times, and the National Review, among other outlets.

Event Flyer

[Music]

[REBECCA HO] It is my honor, today, to introduce Professor James Phillips and Professor John Yoo, who will be providing commentary. Professor Phillips is an assistant professor at Chapman University’s Fowler School of Law. He earned a Bachelor of Arts in history from Arizona State University, and obtained his Master’s degree in Mass Communication from BYU. He then went to Berkeley Law, where he graduated Order of the Coif. After law school, Professor Phillips clerked for Justice Thomas Lee, of the – of the Utah Supreme Court, as well as for Judge Thomas Griffith, of the DC Circuit. He was a Constitutional Law fellow for the Beckett Fund for Religious Liberty, and worked in private practice, focusing primarily on First Amendment issues in Supreme Court litigation.

Joining us today, as well, is Professor Yoo, who I do not need to introduce, so I will not bore you with an introduction. And with that, I will turn it over to Professor Phillips.

[DR. JAMES PHILLIPS] Great, thank you. It’s nice to be back. I have sat in this classroom as a student so, um, well I want to talk today about what I am framing as the most wide-reaching religious liberty case in half a century. I’m not saying it’s necessarily the most important, because that’s, uh, that’s kind of a subjective term, but it’s wide reaching because it implicates the, uh, 1964 Civil Rights Act and specifically Title VII of that, and even more specifically an 1972 – amendment to that. And it’s wide-reaching because Title VII covers tens of millions of Americans; it applies to all private sector employees and government, uh, and local and state government employees, where there are 15 or more employees employed. That’s a lot of people – also applies to the federal government and employment agencies and – and, uh, and unions, so millions and millions of Americans are protected by the 1964 Civil Rights Act. And so a change in what that means and what – and what that protection scope is, uh, will have wide reaching effects.

So what is this case about? This case is about someone who worked for the Postal Service. Uh, and you know, when I was growing up the Postal Service was known to, you know, their motto is we’ll bring you, uh, your your mail through rain and sleet and and hail, uh, except on Sundays. Right, they didn’t come on Sundays, uh, until 2013. And that’s when Amazon came to the Postal Service, which is always bleeding cash, and said: we’ve got some cash for you, if you’ll start delivering our packages on Sundays. I remember the first time I saw a postal truck on a Sunday and I thought: do I have my days wrong, because they, you know, that just doesn’t happen. But that’s what, uh, that’s what led to this case where a postal worker who, for religious reasons, believed that he was not supposed to work on Sunday, because it was his Sabbath. Uh, ended up having this this conflict. I’ll get into the details of the case in just a little bit.

So, here’s the – here’s the act, and basically what it says is that you cannot take some kind of negative employment action as an employer, whether that’s refusing to hire, firing, demoting, failing to promote – any of those kinds of negative employment actions based on certain protected characteristics like race, color, sex, national origin, and religion. Um, well, courts weren’t exactly sure what that meant, and so after some confusion for about eight years, Congress decided to amend the, uh, Civil Rights Act as in – in this instance, as it pertains to religion. And they did it in an odd way; they decided to add a definition of religion, and embedded in that definition is a standard for when an employer knows whether or not they have essentially violated Title VII. And what it is, is, they are required to make reasonable accommodations of their employees’ or prospective employees’ religious practices or observances, unless it would kind of work an undue hardship on the employer. And in those cases, then they would be off the hook.

Well, Congress didn’t define “undue hardship.” If they had, then we would have 50 years of – of a lot less fighting, I guess. So, that raises the question of, what does undue hardship mean? Uh – five years later, in a case called Hardison, the Supreme Court decided to define the term and they defined it as anything more than a de minimis cost. Now de minimis just means trivial, um, and this evoked a lot of criticism, both at the time and later. So, Justice Marshall actually dissenting in Hardison said that he just didn’t really see how simple English usage would permit undue hardship to be interpreted to mean more than the minimis cost.

In 2019, the U.S Solicitor General filed an amicus brief in support of cert. The Court didn’t end up taking the case, but making a similar argument, you know, in ordinary parlance, the definition of de minimis and undue hardship – you do not have the same meaning. Judge Parr, a well noted Sixth Circuit federal judge in a similar case a few years ago said that because Congress didn’t define it, we should give it its ordinary contemporary meaning. And even in the cert petition itself by Mr Groff, he says that this Hardison standard this de minimis plus, as I like to call it, conflicts with the ordinary public meaning of Title VII. So we see this consistent theme by the criticisms. This is not, uh, how you know you would ordinarily understand this term or the ordinary meaning of the term. Now, what they’re – what they’re relying on, here, is this very strong presumption of ordinary meaning and statutory interpretation, or – or textualism. Professor Bill Eskridge has referred to the primacy of of ordinary meaning – it’s the linchpin of statutory interpretation. Justice Kavanaugh said this is statutory interpretation 101, and for two centuries, right, the court has recognized this presumption of ordinary meaning.

What do I mean by ordinary meaning? Well, um, it’s – sometimes you see the term natural meaning, but I think of it as the way my mom would understand the statute. How does the ordinary person on the street use the terms, understand the terms. How do ordinary non-lawyer folks use this? Now, this presumption has become increasingly – or the use of this term, ordinary meaning, has become increasingly used in Supreme Court opinions. You can see here from the graph that it really takes off around the 1980s. Now a little bit of this data can be explained by the fact that the courts sometimes in earlier terms would use synonyms for ordinary meaning, like natural meaning, common usage, plain meaning, um, but that’s not the entire way to describe this.

We also had something going on in the 1980s at the Supreme Court, and that was the rise uh or the the return you might say of of textualism. So in the generation before this, even maybe a couple, few generations before the 1980s, you see a lot more uh, reliance on legislative history in interpreting statutes where the court is saying looking at uh, Congressional records and trying to figure out you know based off of the way the senator, what senators were saying, or representatives were saying, what their intent was for the statute, or the purpose behind the statute. And then, very much a project of Justice Scalia, um, we see the court shifting more to textualism which worries about just what the words mean. Because the words are the only thing that are voted on uh, and enacted into law, and therefore the focus shifted to just the words of the statutes and not what Congress may have been saying in the debates leading up to it, or whatever documents there may have been, so that, so we see this rise of the use of ordinary meaning in in the Supreme Court.

So in the law presumptions are generally rebuttable, and they can be overcome, and there are counter presumptions uh in statutory interpretation. Obviously whenever there’s a definition that trumps, okay? So if Congress decides to define something, however they define it that’s that’s the end of the inquiry. But assuming there’s no definition, Congress sometimes uses specialized or technical meaning, it could be commercial, it could be scientific, and the most common is is is legal. The court, about a decade ago, put it this way: when Congress employs what is called a term of art, we we assume that it knows and adopts the cluster of ideas that were attached to those words and the body of learning from which it was taken. Um, now the most uh, the most common of of these technical meanings that you see, not surprisingly in the law, is legal meaning. Um and so the court has recognized that statutes are often used and they’re from, you know, familiar legal expressions and their familiar legal sense. Um, so when a word is transplanted from a legal context into a statute, it takes all that soil with it. Uh, now you have probably experienced this in law school before, you came to law school, you probably understood the word reasonable, uh, differently than you did after taking torts. Um, and so there are some times when legal terms diverge from what we might call the ordinary meaning.

One of my favorite examples is in the Constitution it’s the term corruption of blood. Now, um, just you know, setting aside what you may know, you hear the term corruption of blood and what does it make you think of? What does that seem like it’s talking about? Any thoughts? Ancestry. Okay, and what about ancestry? Okay, so maybe it’s talking about race. Yeah okay, mixing races, that that that could certainly in the 17, late 1780s, that could potentially be an ordinary meaning of the term. When I when I see that I think maybe of somebody’s sick, right? Um certainly, in you know, George Washington partially died because of bloodletting, right? Uh, the health of blood was kind of a big deal in medicine back then, but has nothing to do with any of that. It has to do with treason, and how the English historical practice, was when someone was found guilty of treason, uh, they were uh, not able to uh, to pass on property to their descendants. It was kind of a Corruption of their bloodline so to speak. Their descendants would be punished for their treason. And the uh, the Constitution, was trying to prohibit that practice here in the United States. So a legal term. We would we could care less what the average Joe on the street, in 1789, thought corruption and blood meant because the Constitution uses a legal term and it takes that legal soil with it.

So, um, uh, when you look at the Court’s cases on statutory interpretation, and you kind of put it all together, you see that there are a lot of things that overcome the presumption of ordinary meaning. Um and and so, that it’s, it is an easily overcome presumption if the evidence is there. And because of that, um I I might frame it this way: it is presumed that Congress uses statutory terms according to their ordinary meaning absent a definition in the statute or absent a sufficient strong or persuasive indication that the term is a commercial term, an industry term, a scientific term, or some other technical term, or any evidence of being a legal term of art that is well settled, widely established, accepted long-standing, or robust, and that comes from a relevant or related area. In other words, there are some steps you got to get to before you get to ordinary meaning, and that’s why my uh, this is actually based on a paper uh, that I’ve I’ve written.

I actually think there’s a three-step process to interpreting statutes when you look at all of the Court’s cases. Sometimes you see it framed as: we just start with the ordinary meaning. But actually I think it that gets it backwards. First, you obviously start with and see whether there’s a stat, a statutory definition. If not, you move to the next step, which to see if whether there’s some evidence of a technical meaning, and if there’s not, then as a last resort, you turn to ordinary meaning. So my argument is that it’s actually ordinary meaning as last resort, not the first step. Because, otherwise, it’s kind of actually rather inefficient to start with ordinary meaning if you’re just going to have to scrap it because you found that it’s actually has a technical meaning.

So, how, let’s apply that here. There’s no definition, right? So now we have to see whether there’s any evidence of some non-ordinary meaning. So, what I did was, I looked in several different databases. So, the first one, and this is also just looking at ordinary meaning, uh, COHA down there at the bottom is the Corpus of Historical American English. It’s a massive database or corpus of uh, documents like newspaper articles, magazine articles, academic articles, uh, and such, that stretch back a couple hundred years. So I looked from prior to 1972, when the amendment was adopted, because textualism freezes meaning in time when it’s enacted, and I only found 10 instances of the term undue hardship across this 400 million word database. And, in fact, most of those were in a legal context. But then I decided to look uh, at federal and state cases, and I found the term shows up over 2200 times. It shows up in federal and state statutes over 1300 times, in federal regs almost 2500 times, and in the Congressional Record, up until 1972, almost 4000 times. This is a term that is very common in the language of the law and very rare in ordinary language. It is not a term of ordinary meaning, at least not based off of this initial evidence. So then I decided to dive into it. And I found that, it is not pigeonholed into one area of the law, it is found across almost all areas of the law. And it’s it’s almost an equitable term – like good cause, or reasonable, and that it’s very contextual, it’s very fact dependent. But sometimes, we see uh, kind of definitions arising up in various uh, places. So we see Civ Pro, welfare, attorneys fees, tax, I like this one: on juries, it’s an undue hardship if you have to go more than two hours, drive more than two hours to serve on a jury, uh, or go more than 80, 80 miles, right? Um but that doesn’t tell us what a new undue hardship might mean in criminal law, or social security, or administrative law, but we see this term over and over again in all areas of the law. However that creates a little bit of a problem, um, because the Court’s doctrine in this area, uh, has two elements to when we assume that this Congress has adopted a legal term of art: first, it has to be widely accepted, or long-standing, or well-settled, or robust, and then it has to come from a relevant context. Well, this is a pretty long-standing term although it seems to vary exactly what it means across areas of law. So the question is, what would be the relevant area of law for the 1972 Amendment to the Civil Rights Act?

And my argument is, that it is regulations by the um, equal uh, employment opportunity commission, and agency decisions interpreting those regulations. Because, the commission was created by the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and the Commission in promulgating the regulation, was trying to flesh out the meaning, kind of gap-filling, as agencies do with statutory uh text, and then the agency was giving additional meaning and a common law style of what in the world this means in this specific context of alleged discrimination in employment. So, in 1966, the agency first started, tried uh, adopted a regulation that proposed a serious inconvenience standard: you don’t have to accommodate your employees or applicants religious needs if it would impose a serious inconvenience on your business, and, there was a lot of criticism of this regulation of being too soft or or too weak. And so in less than a year, they scrapped it, and adopted this undue hardship, uh, standard. Which is all is almost the exact same language that in 1972 Congress codifies into the statute. Um, and then over the next few years, in what Justice uh uh Marshall and his Hardison dissent, called a long line of decisions, the agency started to flesh out what this means in this context. So, this involved a lot of religious minorities, a lot of them were sabbatarians, those are folks who believe that their Sabbath is on Saturday, which creates a lot of conflict with employment. Um and uh, it also involved a woman who described herself as old Catholic, someone who was Orthodox Jewish, and another woman who said that she belonged to the black Muslim faith. And these were things like being able to take their Sabbath off, or having to leave work early because they had to get home before their Sabbath started. One woman had to was mandated by her faith, to attend a two-week annual Convention of her church, and she was trying to use a vacation time to do that and her employer wasn’t allowing her to, and then a few folks there were wearing religious garb. The woman who said she belonged to a black Muslim faith, she actually wore a dress that went to her wrists, and her ankles, and had a high neckline because she believed that’s what she was supposed to wear for her faith, and her employers said that’s not business friendly, and so there was a conflict there. Well over these these 10 decisions in common law fashion, the court kind of fleshes out a little bit of what an undue hardship is. So, it was things like: a practical impossibility, chaotic personnel problems, um, shutting down one’s operations and then suffering exorbitant costs because of having to do that, or undermining a policy that was truly necessary to the safe and efficient operations of one’s business – that’s an undue hardship in the context of employment and religious discrimination.

What wasn’t an undue hardship? Well, giving employees “preferential treatment.” And I put that in quotes because the court says it really wasn’t preferential treatment, because it was required by the statute. Suffering considerable expense, was not an undue hardship. Experiencing employee discontent that was anything less than a chaotic personnel problem, having to train one employee to take over another employee’s shift, or to work an extra shift or an extra day, or switch days. Having an employee on a seasonal basis have to experience a temporary absence, and and they’re not being supervised on a supervised employee was not an undue hardship. And finally, because the court was replacing a serious inconvenience standard with an undue hardship standard, and trying to have a stronger standard, a serious inconvenience it’s also not an undue hardship.

Okay, so Congress knew all of this, they had all this uh, these decisions and they had this regulation before them when they adopted it in 1972. So let’s apply that here to Mr Groff. He’s a rural carrier associate, who provides coverage for absent career employees, he was in um, in Pennsylvania, I think not far from where Professor Yoo, hails from. Um, and and so, he would fill in when when a career employee would be absent. There were other people whose job was to fill in on Sundays and holidays, that wasn’t necessarily uh, his job. And the Postal Service had a list of employees who were willing to work Sundays and holidays. And those who are not, and he was on the not list, and he was originally exempted so long as he would cover someone else’s you know shift on another day other than Sunday. In fact, when Amazon first started uh, contracting with his postal office to work on Sundays, he switched to another office that wasn’t contracting with Amazon, to get out of that conflict. But then later, that office also couldn’t pass up the Amazon cash, and started contracting on Sundays as well, and he wasn’t able to avoid the conflict. Well they were, they originally exempted him, but then after a while they started to schedule him on Sundays, but they knew he wouldn’t show up. So they always scheduled an extra person to work a shift. And so over time other people are having to uh, to work for him on Sundays uh because he was unwilling to.

So let’s think about that. Is, is this an undue hardship, under the way that EEOC regulation was understood, if we go back, is it a practical impossibility for the postal service to schedule someone else? They showed by their own actions that they could do it right? Um, did it create chaotic personnel problems? There isn’t the evidence of that. Did it shut down the Postal Service to not have him show up? No, they, he wasn’t the only person in the world who could do the job, right? There were others who could do it and it doesn’t seem like it really undermined a policy that was truly necessary to the safe and efficient operations of Postal Service. Instead, it looks like these things that are not an undue hardship right? Having to train someone else to take someone else’s shift, um so, so my argument is: that um, undue hardship is not a term of ordinary meaning, it is a legal term of art taken from an EOC regulation and then fleshed out in a series of EOC agency decisions. And it’s that meaning that Congress codified when it adopted the exact same term into the statute in 1972. And, under the canon of legal meaning, we will transplant that soil into the statute, and understand it in that way. Um and, and and if you do that, I think it makes it clear that the Supreme Court should rule in Mr Groff’s favor under this uh, uh corrected meaning of what the statute uh means. So that’s it, thank you.

[JOHN C. YOO] I’ll just make some quick comments and then um, we’ll be able to have questions from the audience. Um I’m so happy to see that you are not disruptive, if you were disruptive I would have to call Stanford and have them send their associate Dean over here to quiet you. But James, unfortunately disappointed, it did not invoke the wrath of the student body.

I think, actually, it’s interesting; I grew up about 25 minutes from the facts of this case. So for those who don’t know about where Lancaster, Pennsylvania is – it’s actually right in the middle of Amish Country. And so the image of the rural what they call it, the rural carrier associate competing with a horse and buggy competition, it doesn’t doesn’t really make me think that there’s a lot at stake here because no matter how fast this guy’s goes, he’s going to beat the competition from the Amish postal service.

But I remember seeing these rural carriers out there too it is an area where uh, there’s almost no town, so people are really spread out and so you actually need these kinds of carriers to deliver uh, the mail because it’s so, the the distances between each house is really this is really far apart compared to, say, in California. Let me ask James a few questions. So one is um, how much extra cost would have to be incurred by the Postal Service to meet undue hardship? So, I was looking up the salaries for rural carrier associates in rural Pennsylvania and so apparently it is $18.47 an hour. So if the facts are accurate, it says that roughly about 20 some Sundays are not covered by anybody, if Mr. Groff receives the exemption. So you’d have to pay someone overtime, so to overtime’s time and a half, so that’s about 27 an hour, and you’d say an eight hour days, so I’m not good, it was like two hundred dollars times 20, is what? Four fifty four hundred, yeah about five thousand bucks. So is that is, supposed he’s given an exception, someone else has to cover they get overtime pay is five thousand dollars and undue hardships. that’s my first question, I don’t know if you want to just take them in order.

[PROFESSOR PHILLIPS] Yeah, I mean, under the way the EEOC was understanding that language, I would say no. Because there were instances where, in one of the the cases the, the employer said well, I’m going to have to pay someone double time in order to take this person shift who won’t work because they, they say they have to have their Sabbath off. That’s a considerable expense and the EOC said that’s not an undue hardship so it doesn’t rise to that level so I would say no.

[PROFESSOR YOO] So then the next question is, does it matter whether, how much the business is making from this activity? For this, so the interesting thing about this, is this is to add Sunday service to, you know, to carry Amazon [unintelligible] packages and before that there were uh, right there was no Sunday service at all. So I figure you could know pretty, with pretty good precision, how much uh, profit the Post Office is making by just doing this Sunday service. Does it not matter how much that 5,000 relates to the overall profit that the post office is making on Sunday? So for example, suppose they’re only making fifteen thousand dollars by doing this, in this region of Lancaster, by the way I can’t imagine a lot of Amish people are ordering stuff on Amazon for Sunday delivery. But suppose there are. Right, so this is 50 so this would be one-third of the profit that’s being made, does that not matter? Shouldn’t you compare it to what the overall profit of the company is in this line of work?

[PROFESSOR PHILLIPS] I think potentially the the uh denominator could matte.r Um, and I think that’s why the this type of uh, this this concept of undue hardship is usually a very fact-based kind of on a case-by-case scenario. So in one instance five thousand dollars may not be undue hardship, but if I’m a mom or pop store, and I’ve got 15 employees so I trigger Title VII, and I’m you know, that eats up 90 of my profits for the day, maybe it would be an undue hardship, right? It probably would be, so I I think it yeah I think the denominator may matter.

[PROFESSOR YOO] So I would say in terms of the statutory language this is probably what the phrase undue mean right? Like you’re going to undue has to incorporate some sense of uh the extra cost, not just cost but also, and this is not included in the tests I saw or in the cases, cost versus actual profit, and that seems to be missed. And so I think that would have to be something the court would have to take into account. Okay then the second thing is wanted to raise was the uh, approach to statutory interpretation which I think is very interesting. So um, James’ argument is that this the rise of plain meaning has things backwards, you shouldn’t start with plain meaning, you should start with um terms of art, technical phrases, and so on. And so the question is why? Why should uh you know professional meaning narrow specialized words be given their meaning rather than what you would call plain meaning, right? And so it just depends on a certain image of the legislature that you must have, which I think is worth drawing out. So it means that you think, that Congress as an institution, when it uses these phrases, is aware of the language that’s used by the profession or by cases and is deliberately incorporating it, even though it has no definition in the statute. So ask yourselves, does this sound like the Congress we all know and love? Is Congress really aware of all the technical phrases and using them? Soes anybody here taking tax or immigration law, do you find the tax code or the immigration code, that Congress is being very careful in the language it’s using and that the code all works together as a whole? In fact usually, in the more technical it gets, I find Congress uses words that are at odds with the same word elsewhere in the code and that they don’t make sense together. So your view is that Congress is part, is rationally acting within a code that is a self-rational and everything coheres together. I’m not so sure that’s the case so that’s another thing to ask, do you think that that’s really the way Congress operates and this is actually an assumption, an assumption we have to accept about the way our legislature works?

[PROFESSOR PHILLIPS] I think it’s a legal fiction that the court has base jurisprudence on. Right, so I pulled up one of the quotes here from the court: where Congress uses a common law term of art in a statute, we assume the term comes with a common law meaning absent anything pointing another way. So uh, I think the court has just decided to countenance this legal fiction.

[PROFESSOR YOO] Oh yeah but you can’t defend yourself by saying the court says that, because you, I’m just asking what do you think does Congress actually operate this way? Putting aside whether the court believes in this.

[PROFESSOR PHILLIPS] I mean I think, I think our laws tend to, at least these days, tend to be written by lawyers. Um, and I think actually there’s a pretty good chance that when they use a term if it has a meaning in the law. I mean, do all of our Congress people have any, have an idea of what’s in the law? No, but they’re not usually the ones writing it. Right? There are specialists behind the scenes who uh, are employed by Congress, or may be assisted by outside folks, who are drafting the language. And these folks are lawyers and they know what these words mean. So I think while it is legal fiction, I think it probably at least a fair amount of the time there’s some truth to it. When Congress uses a legal term or when the statute uses a legal term, it probably is meant to have that legal meaning. But I think there are times when that may not be true, and you have to have certain rules of decision, in order for I think the system to work. Uh and, and so um, I, I think it, you know, it’s a legal fiction that we, that you know, people know what the laws say, right? And, and there’s a thing that in the law where ignorance of the law is no excuse. You can’t say: I didn’t know that was in on the books. We just say sorry, we assume everybody knows all laws. Now that’s completely not true, we have too many laws for any person to possibly know them, but our our system breaks down if we don’t uh, you know, follow that legal fiction. So I think, I think this is a necessary legal fiction that is true a decent amount of the time, especially these days, because legal specialists tend to be writing these statutes, the members of Congress are not writing these they don’t even know it’s in them sometimes. But um but yes, it is not going to always be true, and there are going to be inconsistencies, and you know the court generally tries to reconcile those.

[PROFESSOR YOO] Yeah so the, the reason I asked this, is because it’s based on so your theory of the legislature is based on this law and economics public choice theory of the legislation. Which is, that interest groups really write the legislation, and they make a deal, you know, whether in this case it’s, it would be um, I don’t employers and religious groups. Right? They make a deal about what exceptions should exist for religious belief in employment. And then they go to the legislature, and the legislature it just sort of adopts, legislation adopts legislation as itself the bargain. And that’s why you take specialized words and that’s why you take terms of art, is because the interest groups outside the legislature use those terms. The Congress itself is just this kind of institution which approves the bargains that were political bargains, that were reached by interest groups, and they just need someone to bless it.

[PROFESSOR PHILLIPS] I mean I think that’s, that that certainly happens. There are other times where Congress is more involved in the drafting of a statute and, and then of course there is bargaining amongst the the parties, and amongst the houses, but yeah that sometimes does happen. So the Antiquities Act of 1906, which gets used a lot in environmental litigation, when Congress was drafting that, they were sending it out to uh, specialists, to mark up and provide feedback, and send it back. So sometimes it literally does happen this way and, and other times I think it may not be outsourced to um, special interest groups but, uh, you have staffers, who may be drafting this, um or, or employees of of Congress – you would know a lot more about this having worked in Congress. And, again, I think those tend to be lawyers and people who use specialized language.

[PROFESSOR YOO] So, one last point and then to open it up is what this means about the role of judges. So is it, er would you, would you take the view that this approach, which places an emphasis on legal knowledge, and terms of art, and so on, actually gives judges more power in the interpretive process than they might have if they were just doing plain text? Um, and which, and the reason I raise that, because the ironic thing is that when Justice Scalia started this whole uh, what’s called the new textualism, what actually bothered him a lot was that judges were using these very loose rules of statutory interpretation to just pick the policies they liked. So, as James explained before Justice Scalia appeared, the court would regularly use legislative history as the determining factor a=in interpretation. And in fact there’s a famous case, I can’t remember, from the 70s where the court says something like: well the legislative history is inconclusive so we’ll have to turn to the text of the statue. Right like it’s just like a Justice Marshall opinion, I think it’s a really famous case. And Judge Wald, who is a famous judge on the DC circuit, she gave this famous speech where she said: oh using legislative history is like looking out at a crowd of friends and picking out your friend. That it was just so, there’s so much legislative history, it was never passed by Congress, so it became a playground for the judges to just pick whatever comment in the Congressional Record they liked and using that for. So Justice Scalia started this whole enterprise with the idea of reducing judicial uh power and discretion in this respect, it’s similar to originalism and its purpose and goal. But you might want to ask, did it actually work? You know does does this process that James would have us prefer, it might actually lead to more deference to judges, because they’re the ones who hold all the knowledge of the specialized phrases and terms. Whereas uh you know plain text, which looks out at right, dictionaries, and newspapers, you just generally understood meanings of words by the people as a whole, might have less of this problem, because you could argue more over what regular words mean in regular discourse. But when it becomes legally specialized language, then there’s only a I mean, we’re all part of this class so we make a lot of money off of this but, you know the only specialized class, can you know, has the knowledge to interpret that language, and even if it overrides with the plain meaning of the phrases.

[PROFESSOR PHILLIPS] Yeah I mean, I think when if you’re going to give any credence to the canon of legal meaning, it does give lawyers and judges, uh more more power, in a sense. I don’t know that it leaves them unbounded. Uh because uh, people can look in cases and see how something was used, um just as people can look in dictionaries or newspapers and see how a term of ordinary meaning was used. I think some of the, the arguments in favor of uh, of of a heavier presumption of ordinary meaning is a notice to the public right? I may not know what um the EEOC’s understanding of undue hardship is, but I can hear the words and kind of try to figure that out on my own, and and and therefore there’s this notice thing. Justice Scalia talked about how uh was it Nero? I can’t remember, some some Roman dictator who would put the laws very high up on a tall pedestal so nobody could really see them very well, right? They um and and, when they’re written in a way that the average person can understand, it makes it it’s might as well be written in Greek, right? or Latin. But the the court has long recognized, alongside this presumption of ordinary meaning, that terms do sometimes have a specialized legal meaning. Um and my, my argument is that textualism is not a normative theory it’s an empirical theory. Textualism doesn’t really care whether it’s legal, or ordinary, or specialized in some way. It just cares what the meaning was at the time it was enacted, um, and so it doesn’t have a dog in the fight so to speak. Now you could put a a normative kind of thumb on the scale and say, well we’re going to favor ordinary meaning and there would be benefits to that I think because the uh, folks who aren’t trained in the law might have a better understanding what the law means. I think the better practice would be for Congress to not be lazy and just define things, but we may never reach that date where Congress decides to do that.

[PROFESSOR YOO] So yeah so let me close. It’s uh been great to have a chance to comment on James’s uh talk as you, as Rebecca mentioned, he was the president of the Federalist Society. So he told me, I didn’t remember this, that he was the president of Federalist Society uh, twice, with an intervening year when he was not the president. So he’s like he’s the Grover Cleveland of Federalist Society presidents, and so I think actually now that he’s here we should start a tradition of having a past officer come every year and talk at the end of the semester.

So I think we’re going to do that in the future because of this great precedent you set because it’s a great to see they overcome all their many faults as students and actually turn out to be respectable members of the bar and the profession. So thanks very much James and we’ll open it up for uh questions from the audience.

[PROFESSOR PHILLIPS] Great, thank you.

[Applause]

[PROFESSOR YOO] Oh wait, there’s a mic.

[AUDIENCE] Hi my name is Ryan, I’m from the business school. I actually had a question: do you mind going back two slides to the the test for undue hardship, was like, you have to shut down business. uh I think there’s one of the tests is like uh, sorry uh, shutting down one’s operation. So I guess I so one idea that popped in my head, is that, does it also look into opportunity costs? Right in terms of, you have one place you could say: well I have to shut down business to support this, you know, religious exemption, but could you also look at it as another way? And say let’s say you’re a high growth tech startup, or in this case, the post office is expanding into Sunday to increase revenue, then could you argue that one aspect of undue hardship may be foregoing potential business? But then that also goes down a slippery slope, is then how do you quantify the opportunity cost? Right because if you look at some of the tech startups you could say well, year over year growth rate could be 300 percent. So does that qualify as an undue hardship then if I’m allocating resources that might be small on a numerical basis, but may go huge like business opportunity costs in capturing market share and revenue growth etc.?

[PROFESSOR PHILLIPS] You know I think, I think courts are going to be a little hesitant about uh, future possibilities and quantifying those. um so I’m not saying that they wouldn’t potentially take that under consideration, again this is very much going to be something that’s, because it’s it’s kind of an equitable term like good cause or reasonable, that courts are going to kind of flesh this out in in a common law style and look at the facts of the particular case. So it I could imagine a potential scenario, that this one particular case was an Orthodox Jewish gentleman, who was a very specialized engineer, and had to have his, had Saturdays off and it would require shutting down the plant that he was assigned to. And they said that would be an undue hardship right? I think the more specialized someone is or the more integral someone is to a company’s operations, including potentially future the more likely it’s going to be an undue hardship to give this person a day off or or whatever it may be. But again, I think the courts like, they tend to want a more of a concrete harm rather than, well if we if we do this we think we’re not going to be able to do X, right? I think that’s going to be a little bit a harder sell for employers to make that but I’m not saying they couldn’t. Again, this isn’t the standard I would pick, I’m I, prefer rules over standards because you get the bright line. Even if they’re sometimes wrong. So I’m more of a rules guy than a standards guy, but Congress adopted a standard. And when they do that, the courts have to follow whatever the statutory language is. So, so maybe, but, but again I think it’ll be it would have to be pretty clear I think for a court to countenance that future projection. Yeah.

[AUDIENCE] Um so accepting that courts should look towards the legal meaning in a statute–

[PROFESSOR PHILLIPS] If there is one, right? A lot of words in a statute have no legal meaning.

[AUDIENCE] Yeah that’s kind of my question, is how do you determine if there is or isn’t a legal meaning? Do you look at like the temporal con, like connection, do you look at the context? It might be an easy case of the EEOC but if it’s more difficult that seems to me to start to blend into almost a legislative history type analysis which is kind of against in my view what textualism is.

[PROFESSOR PHILLIPS] Oh I agree I agree. So here’s how I would recommend doing it. I would start with Westlaw, and I’d say does this term show up a lot? Oh it does? Okay. And again I would limit it to the time period leading up to the date of enactment, because any post-enactment usage is irrelevant, because you cannot amend the meaning of a statute through things outside of the legislative process. And then if it does show up a lot, I would see well is, is it being used in the in the relevant context? Right, so if undue hardships showed up all the time in civil procedure but never in any kind of employment discrimination type of a context, I’d say well that isn’t I, it’s not clear that, that’s that’s what Congress was you know, that’s that’s the meaning that should be given here. Um, so that I I mean that’s what I did here. I just said, I just wonder if this term shows up a lot. Whoa, it’s all over the place. It goes back to like 1834, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court first used it. Or um, and so, that got me, you know, that was like oh, there’s some initial evidence that this is a legal term. Whereas when I looked in ordinary meaning uh, you know a corpus or a database, it’s very rare. That was the initial, started the the initial process of investigation. So I think a judge can do that, a party can do that. They can put the term into Westlaw right? Um, and just see and if it doesn’t hardly show up that much, that may mean that there’s no legal meaning to it. Now it could show up a lot in the law but actually have an illegal meaning, you’d have to kind of figure that out. The term police probably shows up a lot in legal materials, but probably doesn’t have a legal meaning. Right? It’s probably being used in an ordinary meaning but it’s being used a lot just because of, of legal context. So it doesn’t necessarily mean if it shows up a lot in the law that it has a legal meaning, but it might be it’s like initial evidence so that’s where I’d start.

[PROFESSOR YOO] I mean can I just throw in something I think that while the microphone moves over, is um on Daniel’s point, which is if you do think about legislation as like a contract between two interest groups, that use the legislature to be you know like the court in a way. Then um, there’s a lot of work actually on why do contracting parties define terms some terms in the contract and sometimes they don’t. And one thing they talk about is right, getting, if you’re negotiating someone with a contract, and you try to put a definition in, that’s going to cost right? That’s something that’s part of the bargaining, you’re going to pay for the definition. And so I found when I worked in Congress often, what would happen, I mean they are aware of this problem, obviously, so they don’t put words in the definitions because they don’t want to have to negotiate with the other party for it. So why would you do that? One, you would do it because you can’t come to agreement, so both of you are content to let the legal system and the courts fill in the definition. And you have some view there you think you’re going to win, based on what will happen in the future. Right? And then the other the other reason, is the reason I think you’re using, which is: oh everyone knows what this word is so there’s no reason to define every single word and the claim then is that the more that something is a term of art, the more both sides have this expectation that it will be interpreted in a certain way. That’s actually kind of an empirical question maybe more than um, right because you could actually test that to see whether it’s actually borne out by in the past. So yeah.

[PROFESSOR PHILLIPS] Strategic ambiguity I think is the first thing that you’re referring to, right?

[AUDIENCE] Thank you so much. Um so one case, uh talks about the idea of Congressional ratification of a court decision by silence. And thinking here of Owen’s Equipment v Kroger, which addresses like an 1806 understanding of subject matter jurisdiction, and then looks at the fact that Congress hadn’t changed subject matter jurisdiction over the next 150 years, and says that’s good enough. Congress doesn’t have any other meaning other than what’s been there because they’ve had many opportunities to change it. Now, here we have a 1970s era a case that defines undue hardship as de minimis. Um and we have Congress coming back to title seven a half thousand times since that case, um has Congress ratified this definition of undue hardship through their silence?

[PROFESSOR PHILLIPS] So I actually, I mean I don’t subscribe to that theory of cons, of statutory interpretation. I think it’s inconsistent with textualism the meaning is solidified at the time of enactment and cannot be changed after the fact. So the Supreme Court cannot technically change the meaning of the statute. Now as a practical matter, in our legal system, do they functionally do that? Yes. But does that mean that’s what the statute meant when it was enacted? And does that mean, so, and the thing is, Congress may may not have really acquiesced, they may not they just may have been had gridlock. Right there’s there’s something called observational equivalence where you can explain the same phenomena with different uh, explanations. It could be that Congress said: oh yeah that’s what we meant or, oh yeah we’re okay with that we’re not sure what we meant but we’re okay with that, or actually we don’t like that but we can’t agree on on on the fix on on how to overcome Congress or the court. Because of those reasons, I don’t really like countenancing Congressional silence as acquiescence to a judicial interpretation of a statute. I think you just look at the uh, the evidence, the public evidence whether that’s ordinary meaning, or legal meaning, or some other specialized meaning leading up to the time of enactment, and and, I think that’s the the limit of what you look at uh for for a textualist interpretation.

[AUDIENCE] Yeah so I’m still a little confused on what would count under this test as a practical impossibility. Because it seems to me to be entirely reliant upon the number of employees you have who say I need to take off that Sunday. I don’t know how any employer would be able to see this and go all right if I only hired two people who need to miss on Sunday I am in the clear, but if I have five people have to miss, all of a sudden, I’m now getting into this whole headache of okay I can do this but I can’t do this it seems to God, not give any clarity.

[PROFESSOR PHILLIPS] Well that’s part of the problem with standards right? Uh and and when they’re worked out in common law fashion. I mean, what kind of clarity does being a reasonable person have in tort law, right? It’s, it’s, it’s a little fuzzy. Uh the particular case where this came out of involved a woman, actually I think it was a high school uh girl, who um wanted to have Saturdays off, she was a Seventh-Day Adventist. She was only hired for six weeks um, and uh, it was a seasonal job, and the employer really didn’t have someone that they could train to just come in for one day for six weeks. It just, it just wasn’t, it was a practical impossibility the EEOC found for that particular scenario. Now I think what you’re saying is, a lot of the times you know, the way things operate these days, and the way people are fungible, um it’s not going to be a practical impossibility. And that’s okay, because this is a civil rights act. Right? It’s supposed to be protective of people’s civil rights. But I do think – and certain employers like that Orthodox Jewish engineer who had very specialized training – a certainly smaller employers perhaps you might be more likely uh, to find practical impossibilities. So again it’s going to be very text, contextual and case by case. I don’t think Amazon for example right, they’re, they’re going to struggle, unless it’s like somewhat someone way high up, and they’re really needed on that particular day to, you know, to be able to show an undue hardship.

[PROFESSOR YOO] Well I was going to follow up there too, and say, I ask you uh, what do you think would happen if your argument prevailed? What will employers do? Won’t they like in their job postings put like the most difficult conditions on the job for religious people to satisfy, so that no one will ever apply? And if they do apply that you’ll be, you’ll be told you must work Sundays to apply for this job, and you can’t like apply for the job show up and say: well I don’t want to work any Sundays. Won’t the employer say look I put in the job description Sundays are required, so isn’t that going to be the next response after this? And then would you say that they still have to be subject to Title VII liability if they were clear up front when you were hired you have to work Sunday, or you know, or work in certain ways that would by nature exclude various religious groups?

[PROFESSOR PHILLIPS] Well I mean title 7 does apply to applicants as well, uh and so I think uh, they wouldn’t necessarily be automatically off the hook. if they just say we expect you to be able to work seven days a week. Because the question would be, would it be an undue hardship to give that person one day off a week? Right? Because my guess is most employers aren’t requiring people to work seven days a week. They are requiring them to be available seven days a week. And that means that they have other people who will be available on that day that that person necessarily wants off, and that person may be willing to work on the other day. So I do think though, that businesses aren’t going to be happy if the court follows this. And they will try to figure out I mean this is just what happens right how do we respond to that? And that’s up, and and if the response is in such a way, that it is uh perhaps undermining religious applicants or employees, but consistent with the law. Then that’s Congress’s problem to deal with. Um you know, and and and you know in, in an ideal world legislation should be updated as the world changes. Uh that doesn’t mean that that’s always how Congress works. But I think I think some some will try that, and we’ll just have to see. Then there’ll be test cases right? Where the employer says: well I require everybody to work seven days a week. And the person says: you know but that’s not an undue hardship for you to find in a replacement for me when I’m gonna cover for that person on their day off. Um, and they’re willing to work on Sunday because they get paid more. And who, who doesn’t matter who you’re paying so um, yeah again, it’s a standard – it’ll get fleshed out. Uh it would be mine. Yeah.

[PROFESSOR YOO] I mean if I hope this never happens but if I work for the Postal Service, what I would do is I would say okay we’re going to hire people for Mondays people for Tuesdays, right and there’s going to be a certain class, people who work only on Sunday.

[PROFESSOR PHILLIPS] Because they have those that’s the assessment-

[PROFESSOR YOO] Yeah that’s what this case actually allows, shows that you could do that. So that’ll be the next case, yeah maybe so how can you say that’s illegal?

[PROFESSOR PHILLIPS] Yeah I don’t know, I mean we’ll just have to see. I I I, again it’s so fact-based, that it’ll probably depend on the employer, and and the nature of of their job, and and all that. And again I don’t love that, I wish there was a bright line definition um but that’s that’s what we’re stuck with until Congress decides to change their mind.

[PROFESSOR YOO] Do we have any other questions.?

[REBECCA HO] If we don’t have any further questions, please join me in thanking Professor Phillips and Professor Yoo. Thank you.

[Applause]

[Music]