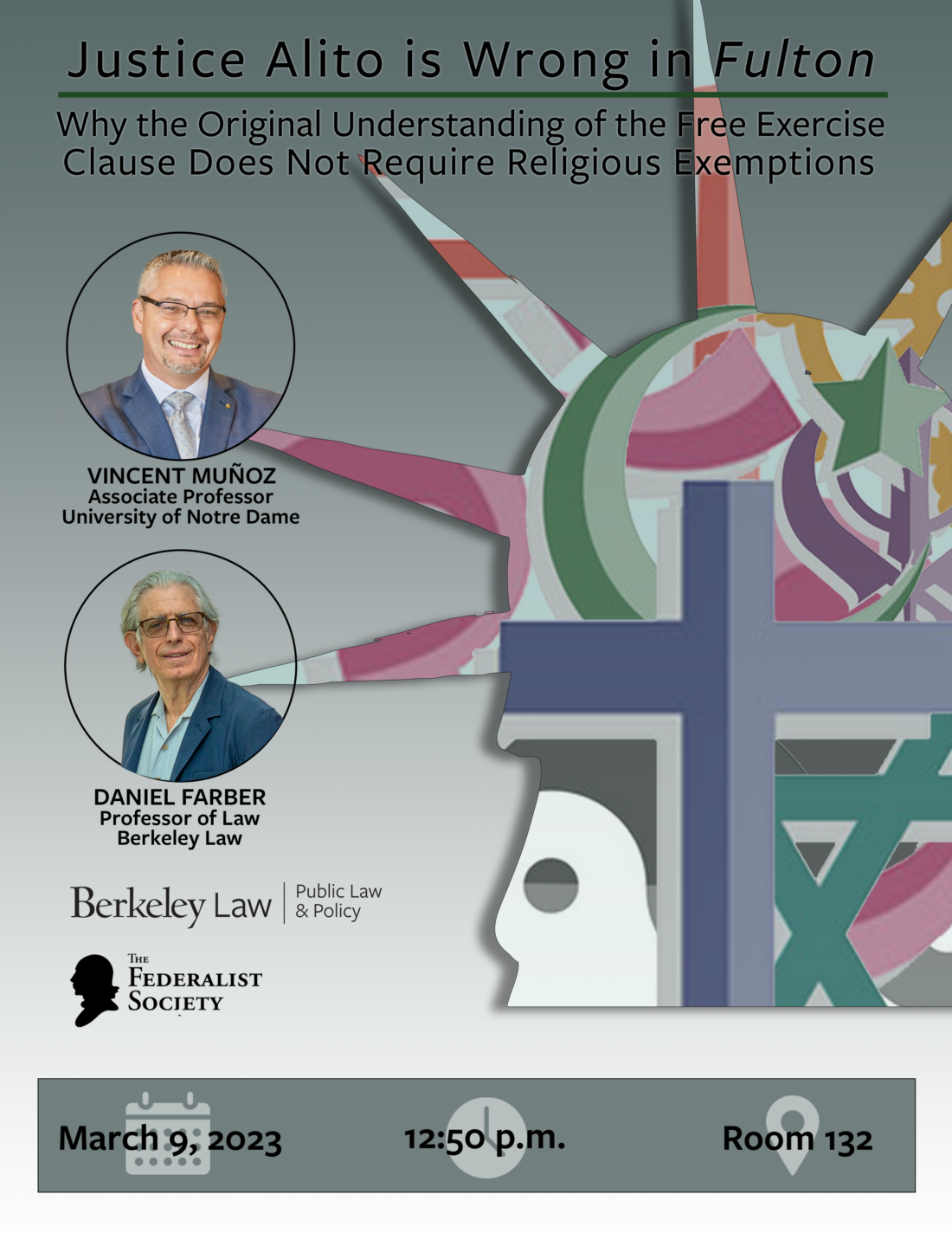

Justice Alito is Wrong in Fulton

Thursday, March 9, 2023 | Room 132, Berkeley Law

Event Video

Event Description

The Public Law & Policy Program and the Federalist Society, Berkeley Chapter, presents Professor Vincent (Phil) Munoz (Notre Dame) as he opines on Justice Alito’s interpretation of the Free Exercise Clause in Fulton. Berkeley Law’s Professor Daniel Farber provides commentary.

Panelists

Vincent Phillip Muñoz is the Tocqueville Associate Professor of Political Science and Concurrent Associate Professor of Law at the University of Notre Dame. He is the Founding Director of ND’s Center for Citizenship & Constitutional Government. Under his leadership the programs have raised nearly $20,000,000 in grants, gifts, and pledges.

Event Flyer

[Music]

[STEVEN HAYWARD] I’m Steven Hayward, fellow at the Public Law & Policy Program, and your moderator and host of the day.

A brief introduction to the average citizen on the street, I think you might say the First Amendment was thought to solve the basic problems of sectarian political conflict. Or, as I like to joke sometimes, the First Amendment created a space for safe sects. You say that one slowly and carefully so that people must understand it right. And yet the subjects always in court there’s always seems to be a controversy in court about religious liberty; about whether something breaches The Establishment Clause in the First Amendment. And as law students of course, you’re trained to learn all the fine distinctions and various tests that have been promulgated through the case law over the years. And then we have novel conflicts, uh if you’ve been following the conflict for over a decade now involving a certain banker in Colorado, and whether freedom of religion conflicts with some modern doctrines of public accommodations and civil rights laws. Entirely intelligible conflicts that maybe nobody thought to see coming 40, 50 years ago, certainly not in 1789.

Well our principal guest speaker today, Phil Munoz, from the University of Notre Dame, is urging us to step back for a moment and recover our bearings from the natural rights foundation that shape the thinking behind the First Amendment. In other words, to keep us from missing the forest for the trees. He lays out this argument in its fullness in his new book Religious Liberty and the American Founding: Natural Rights and the Original Meanings of the First Amendment Religion Clauses. Meanings plural, emphasize that in the subtitle, just out from the University of Chicago press. He’s going to speak on a subset of this very rich book, you see the title about religious exemptions in the free exercise clause, which have been a very live issue at least since Smith versus Employment Division, if not really much earlier than that.

And to comment on Professor Munoz is our own Dan Farber, who I hope is well known to all of you. So I’m going to limit my introduction to saying that he is the author of several of my favorite books, to argue with. And I say that not because I think they’re wrong, but for the opposite reason; because I think they’re largely right, albeit derived from different methodologies and approaches of my own. And that always makes for the most interesting kinds of dialogues. In particular I’m a fan of his book Rights Retained by the People of the Ninth Amendment; Lincoln’s Constitutionalism, a book I say “gosh I wish I had written that”; and then also a little older book, with Susanna Sherry, Desperately Seeking Certainty which I think is a great survey, maybe a little out of date with the way originalism is fractured, but that may come up some during our discussion today with Phil. But with that Phil Munoz, please guide us through what you think we should think differently about.

[VINCENT PHILLIP MUNOZ] Well thank you Steve, for that kind introduction. Thank you to the Federalist Society, especially its leadership, for the kind invitation to speak with you today, to Professor Farber thank you very much, and Professor Yoo who helped set up the visit. Um I-I’ve got to know Professor you over the last few years, we do some summer teaching together, and we don’t always agree about the Constitution, we certainly don’t agree about its underlying principles, um but his subtle criticisms, uh and learned questions have been quite valuable to me to sharpen my scholarship. And he’s become a dear friend, and so I’m very pleased to be back here and to be able to spend some time with him – and I thought I’d do this lecture again for him so maybe he’d understand it this time.

So I’m going to begin with the story, this is a true story. On the morning of June 17 2021 I was on the road with my family and our Honda minivan, wife in the passenger’s seat, three kids ages eight, six, and four in the back. We were driving to a Great Wolf Lodge water slide park in Wisconsin, some of you may be familiar with the Great Wolf Lodge. I presume Professor Yoo is not. Um, for those of you who are familiar, this is what your future holds for you, you become someone, someone like me at my age. Parents endure these hotels childrens love them.

Uh, somewhere between Chicago and Milwaukee, this is a true story, my phone just explodes. Um it’s buzzing buzzing buzzing, I’m driving so I can’t look, my wife is asleep, my kids are watching videos. But my phone keeps on going off, turns out that morning the Supreme Court decided a major religious liberty case, Fulton versus city of Philadelphia. My phone was buzzing because my scholarship had been cited multiple times by Justice Alito. A small section of the opinion, of his opinion, was devoted to a law review article I wrote. And so, my friends and colleagues were calling to congratulate me. This is what you want when you teach in a law school. So we get to the water slide park, I quickly check my email, I find a nice note from the dean of the Notre Dame law school, he says he’s putting up a story on the website, this is that story. Other professors were cited too, I don’t read the opinion at all because I’m spending the whole day going down Howling Tornado in an inner tube with my kids. So that evening I get my kids in bed, uh, pour a cheap glass of wine from the Great Wolf Lodge store, and I sit down to read the opinion.

And there there it is, Justice Alito cites my work multiple times, in fact he highlights it. He says there’s one originalist scholar who has recently done new work on the original meaning of the free exercise clause, and that scholar Justice Alito says, that scholar gets the Constitution’s meaning exactly wrong. To make matters, uh, even less comfortable for me Justice Thomas and Justice Gorsuch joined Justice Alito’s opinion, and Justice Kavanaugh and Justice Barrett seems sympathetic to me. So at least three originalists on the court, and probably a majority of five, think the project I’ve devoted most of my scholarly life to is in Justice Alito’s choice words “unfounded.” Now thankfully I’m not alone on my side, Justice Alito also said that Justice Scalia got it wrong in the landmark case 1990 case Oregon versus Smith.

In his Fulton opinion, Justice Alito called for a reversal of the Court’s leading free exercise precedent, that is Scalia’s opinion in Smith, and a return to what I’ll call the “Exemptionist Approach.” So this is my chance today, to respond to Justice Alito. I don’t presume to speak for Justice Scalia. But I’m going to make the case to you, uh my case to you, at least part of it as to why I think Justice Alito is wrong, and why the Founder’s understanding of a natural right of religious liberty, does not include a constitutional right to exemptions from otherwise valid laws.

Okay, so let me just quickly sketch the dispute between us. The First Amendment protects the free exercise of religion, obviously. Justice Alito holds that the constitutional right of religious liberty provides religious individuals and institutions exemptions from otherwise valid laws, that in practice burden their religious beliefs and practices. I hold the contrary view, that the free exercise clause does not provide exemptions. Two examples just to clarify the differences, probably not needed for the law students, but let me just use them in case you’re not familiar with this debate. At the time of the founding, Quakers refused to take up arms on account of their pacifist religious beliefs. Justice Alito would hold that the free exercise clause would protect the Quakers and give them a right to an exemption, at least assuming that the state’s not pursuing a compelling state interest. So the Quakers get an exemption, if Alito is right, I guess I make them fight. Second example, and I choose these examples because they should elicit support for Alito’s position and not mine. This is from the 1970s, and I just choose this because I was driving to Wisconsin, and this case is from the Wisconsin. Um, in the 1970s, Wisconsin had a mandatory school attendance law, the case is Wisconsin v. Yoder, you had to send your kid to school until they were 16. Some old order Amish they, because of their religious beliefs, took their kids out of school after the eighth grade, approximately 13 or 14. Superintendent of Public Schools in the state of Wisconsin, started fining these parents every day their kids were not in school. Parents say “but we’re doing this for religious reasons, we have a First Amendment right to be exempt from this mandatory school attendance laws.” If Justice Alito is right, the Amish are exempt from the mandatory school law. If I’m right, they’re not. Now I should make clear that Alito’s exemption approach does not mean every religious believer, in every case, is exempt from every law. The test, as I’m sure you know is: is the state pursuing compelling State interest in the least restrictive means. But the, but the religious believer or institution gets the benefit of the doubt. Right? In practice, um, the expectation is that they would get an exemption.

Okay, let me, let me briefly summarize Alito’s position in Fulton. And this is from part three of his concurrence in Fulton. Alito said, it’s a textual opinion, he says we must begin with the Constitution’s text. Proper interpretation, I’m quoting him, um uh, “what readers would have understood its words to mean when adopted. The proper starting point is to consider that normal and ordinary…” again this is his words, “…normal and ordinary meaning of the words ‘Congress shall make no law prohibiting free exercise of religion.’” Alito cites Samuel Johnson 1755 dictionary, this is typical of textual opinions, uh and he relays that, to prohibit, means either to forbid or to hinder. Johnson’s dictionary, he continues, then provides two definitions for the term exercise. There’s a broad definition, and that is to practice, or outward performance, and a narrow definition, a narrow definition is an act of divine worship whether public or private. So the broad meeting is broad because the religious believer herself defines what constitutes a religious exercise. So any action, not working on Saturdays, homeschooling, feeding the poor, any action could follow within the category of a religious exercise, because the category is defined by the beliefs, motivations, and self-understanding of the religious believer himself or herself. The narrow meaning is narrow, because what constitutes a religious exercise is defined by an objective, ontological reality. Some actions are just by their nature religious, others are not, even if they are religiously motivated. So what constitutes a religious exercise in the narrow view, is not defined by the believer, but rather by certain properties of the activity. Right, there’s a form of religious exercise to go back to, you know reading Plato. So traditional religious worship services, or say the Catholic sacrament of confession, these clearly would be examples of religious exercises in the narrow meaning. Whereas, I don’t know, submitting plans for a church building, or an activity of feeding the poor, or withdrawing your children from school, probably would not be religious activities. These definitions are not exactly precise, but they capture the two ways that for the exercise was used at the time of the adoption of the First Amendment, according to Justice Alito’s use of the dictionaries at the time.

So that leads to a question, which meaning of exercise should be regarded as the normal and ordinary meaning, in the context of the First Amendment? What’s the original meaning, the broad meaning or the narrow meaning? And here, somewhat surprisingly, Alito departs from textualism at this crucial point. And instead he appeals to precedent, there’s a very good law article, law review article, waiting to be written on exactly this point: a supposedly textual opinion, in the key moment, is not textual at all. Right, Alito writes the key key passage “the court long ago declined to give the First Amendment reference to exercise the narrow reading,” and he cites Cantwell versus Connecticut. So he dismisses the narrow reading of exercise via precedent, and therefore concludes in favor of the broad construction. Now Alito is right about precedent, there’s no doubt about that, but whether that precedent correctly interpreted or presented the original meaning of the Constitution’s text, is a completely different question. And Cantwell was in no way an originalist opinion. So I don’t actually think precedent does, or should, resolve the matter. And to be candid, I don’t think dictionaries are textualism alone can determine, what readers would have understood the free exercise clause to mean. To use Alito’s standard. But I am confident, and I’m going to present to you, I am confident that the Founder’s philosophical understanding of religious liberty, and their underlying natural rights political philosophy, that is the political philosophy that originally animated the Constitution, it, those, can resolve this question. And grasping the Founder’s philosophy I’m going to argue, reveals that the narrow reading, and not the broad reading, is the reading most consistent with the First Amendment’s original understanding.

Okay, okay. Following Alito, let me begin with the First Amendment’s text, right, okay. Two things to note about the First Amendment: first, the First Amendment is about power, specifically about congress’s law making power. Not all the provisions of the Bill of Rights are so clearly directed against Congress. Third Amendment is directed at the protection of homeowners, it would seem to apply to Congress and the executive. Fourth Amendment’s protection against unreasonable searches and seizures, would apply primarily, I would assume, against the executive, but also against the other branches as well. But the First Amendment, is directed at Congress’s power. Second thing to note: the text of the First Amendment, at least the free exercise clause, is categorical: Congress can make no law prohibiting the free exercise of religion. Other provisions of the Bill of Rights are different, take the Fifth Amendment’s protection and property rights: you can be deprived of your property, but due process, and your property can be taken, with just compensation, for public purposes. So the two immediate observations I would make about the text, that is whatever the scope of the protection is, the First Amendment’s text, and an interpretation of the First Amendment consistent with the text, ought to be directed against Congress and its law making authority, and it ought to be categorical. And I derived that simply from the text itself. Okay, but that doesn’t answer, what is the free exercise of religion that Congress cannot prohibit? Let me note here, just for the sake of time, I’m going to assume that we ought to be originalists here. Now, I think we could actually have a very interesting question whether we should be originalist, and I’m certainly happy to have that conversation, there’s really no one better to have that conversation with than Professor Farber. But I want to meet Alito on his own terms, and the, the five, what seems to be a forming five-member majority, on their terms, and they appeal to originalism. Okay.

The clearest evidence we have, of how the Founders conceived of the right of religious free exercise, is not actually in the First Amendment, or the Bill of Rights drafting record, rather the clearest evidence of the founders thinking about these matters is the state constitutions and declarations of rights drafted between 1776 and 1784. When they talked about religious free exercise, the Founders everywhere said the same thing: religious liberty consists in the natural and unalienable right, that’s their term, unalienable right, to worship according to conscience. So if we want to understand the founders, we have to understand what they meant by a natural right, and what they meant by unalienable. Now I just want to give a trigger warning here to Professor Yoo, he gets nervous when I start talking about this sort of language. Natural rights are different from acquired rights, that’s a term the founders used, acquired rights. To put the matters in just in simple terms, natural rights are not created by the state. They exist prior to the existence of the state, they’re part of the moral fabric of the natural order. Their author is the creator or as the Declaration will put it nature and nature is God, that’s why they’re natural rights. We have natural rights on account of our human nature, we create government at least in the founders understanding, to protect our natural rights. Natural rights do not come from the government. Okay, I mean, I think everyone would agree with that, at least in the Founders’ understanding. What is an inalienable right, what were, what work does the word inalienable or unalienable do? Well it turns out in the founders understanding, there’s two types of natural rights: inalienable natural rights and alienable natural rights. And so the key to grasping the founders understanding, is right here: grasping what they meant by an inalienable natural right, how are inalienable natural rights distinguished from alienable natural rights. And to understand this you know fundamental part of the founders thinking, requires we briefly review their social compact theory of government. And here, here, sorry I’m one slide behind here, let me just go for it.

Okay, um, there are three basic steps of the Founders’ social compact theory: human equality, governments institute, so all men are created equal, that means [unintelligible] well we’re equal in certain natural rights, we institute government to protect rights, um, legitimate government is via consent, and then some rights are inalienable. And we can talk more about that if if you like, um the the easiest way actually to explain this is through an example, so let me use this example: you have a natural right, an alienable natural right to acquire property. By your, by nature, you own your own labor right, you, I mean, you say like you know, so you pick the apple, it’s your apple. Why is it yours? Who said so? I mean every two-year-old understands this. And well, it’s because we, it’s not that we own our own body precisely, we own our own labor, so if you pick, it you mix your labor with something that’s not owned by anyone, it’s it’s yours. That’s by nature. Okay, let me use the example of fishing. So let’s say you’re on the Bay, I assume no one owns the Bay, and you’re fishing. I don’t know that you’d actually want to go fishing out in San Francisco Bay, but let’s just assume you are. Um you catch the fish, you have a natural right to acquire property, acquire property and fish, you go out and fish, you whatever fish you catch is yours, okay. So this is, I was making the slideshow with my kids in the room, so these are two of my kids out fishing. Um now there are natural limits to natural rights. The right to acquire property is not unlimited, there’s a law of nature the Founders say that governs the state of nature. The law of nature is that I can’t take um, obviously I can’t take the fish others have caught, but I can’t take more fish than I can use, that’s the limit of spoilage, and I have to leave enough fish for others. This is straight out of Locke’s second treatise.

So natural rights have not-natural boundaries. But there’s no authority in the state of nature, right that’s the definition of a state of nature, there’s no common authority, there’s no police force, which means every individual has the executive authority of the state of nature. So if someone takes too many fish, everyone can punish the violator. And once you have kids my age, you will know that they understand these principles by nature. So I have the authority to fend off those who would steal my fish. And similarly, others have the right to punish me for taking too many fish, that is for taking more than my fair share, not leaving enough for others. This is all basic social compact theory state of nature thinking. There are two great inconveniencies, to use Locke’s term, of the state of nature. The first is that individuals are unjust, they take more than their fair share and they take what belongs to others. The second is, it’s not always clear what the Natural Law dictates in specific cases. So how many fish is too many to take? Even if you agree to the general rule: don’t take more than your fair share. That is, more than, well you know that you don’t take more, don’t deplete the lake, you got to leave enough for others. How much is too much? That’s not clear, even if we agree to the principle. That, and that’s where disputes happen. So in the state of nature, because of reasons of injustice, but also because of uncertainty, the state of nature tends to lead to disputes, it tends to become a state of war. War where rights are not secure. This is why we institute government, we institute government to protect our rights so we can fish, but only catch the right amount of fish. I think here in Federalist 51, if men were angels, no government would be necessary. Right, my very religiously devout Catholic students tell me, well actually, angels would need government. I don’t actually understand that argument, um, but in Madison’s thinking, it’s because we’d have, we’d all be just, we wouldn’t take each other’s fish, and we’d all understand, we’d all be reasonable, we’d all know exactly how many fish to take or not to take. But men are not angels, so government is necessary. We institute government to protect our rights, but we alienate our rights.

So what does it mean to alienate our rights? We alienate our executive power to enforce the law of nature, right, that is when you take too many fish, or if I take too many fish, you call the police. You don’t enforce the law of nature yourself. That’s the foundation of executive power. We also alienate our power to make determinations about the law of nature, that is how many fish are too many to take, this is the foundation of legislative power. So we give these powers to government, both executive power and legislative power corresponding judicial power, that’s that’s what it means to alienate our rights. It’s not that we give up our rights, we give up power to enforce our rights and to make determinations about the content of the natural law by which our rights are protected. Okay. Good government, makes laws, positive laws, civil laws, consistent with the natural law. The purpose of government is to regulate our rights, but not in the modern administrative way. Regulate, is to make regular, that is to facilitate the enjoyment of. So the purpose of law, is to facilitate our right, all of our rights, to acquire fish. So we have regulations, you can take, you can catch you know, six fish a day, you can fish from these hours. And the reason we do that is so we can all enjoy fishing, that is so we can all enjoy our natural right to acquire property. The tragedy of the commons right, that’s why we need government.

Okay, let me get back to the main thread of the argument. Why am I talking about fishing? We’re trying to understand, in what sense we alienate our natural rights when we make the social compact. We’re trying to understand what an alienable natural right is, so we can understand what an inalienable natural right is. We’re trying to understand what an inalienable natural right is, so we can understand the Founders’ conception of religious liberty. We’re trying to understand the Founders’ conception of religious liberty so we can interpret the free exercise clause according to its original meaning. Everyone follow the steps there? I know this is not typically what law professors do, but this is what you actually need to do if you want to understand the text of the First Amendment, at least the original meaning. We figured out in what sense we alienate our natural rights in the fishing example. When we alienate our natural rights, we give authority to government to regulate our rights. So our natural rights become civil rights. And we grant government authority to enforce laws that are made to punish violations of our rights. So if that is what it means to alienate a natural right, what does it mean if our rights are inalienable? Well it’s not that hard to figure out right? So inalienable rights means we do not give government authority to make laws to regulate our non-alienated rights, what we possess in the state of nature we possess in civil society. So we don’t give that legislative power, and because government lacks authority to legislate on the subject of our inalienable rights, government lacks the corresponding executive power. If that seems too abstract, let me just give you a simple example. The right to revolution is an inalienable natural right. Right, the government can’t secure your right to revolution. Right, you you don’t even here at Berkeley, right? You don’t go to the authorities and say, I’d like a revolution license, you know so I can practice revolution from, you know, three to five on Friday afternoons. It’s the nature of the right is nonsensical. I mean it, it’s nonsensible, of course it’s you inalienable. Revolution is never legal, I don’t know maybe it is here actually, but in most places it’s not. Right, you can’t give government authority to regulate your natural right to revolution. The nature of the right prohibits it. Thinking about revolution helps us see that inalienable rights refers to categories of things, or areas of our freedom, or do we we do not give government power. Inalienability in other words, is a jurisdictional concept. If a right is inalienable, we do not give government authority over the right. Government cannot legislate on that particular subject matter because we never gave government such authority. This is just a visual depiction of what I just said.

The inalienable right of religious free exercise corresponds to those areas of religion over which we do not give government power. So then the question becomes, what power over our religion, exactly, do we withhold from government? What is the category, or the subject matter, of religious free exercise that is inalienable? Whatever is this category, of non-alien non-alienated religious freedom, we not we we know it’s also not in the category of alienated rights. Right? Does everyone follow that? A thing cannot be and not be at the same time, we cannot reserve and alienate authority over the same right. It’s a mutually exclusive category, everyone see that? Okay, so the law of contradiction means a right cannot be alienable and inalienable at the same time.

Have you anticipated my argument? We’ve already answered the question about whether the re, right of religious free exercise, includes a right of exemptions from otherwise legitimate laws. Otherwise legitimate laws, are in this category, our first amendment rights are in that category. It makes no sense to say the First Amendment gives us exemptions in this circle. Everyone follow that? Let me go back to those founding era State declarations. What the founder says is, inalienable is the right to worship God according to conscience. That’s literally what they said over and over. When the founder spoke about the inalienable character of religious freedom, they spoke in terms of worship. Through, thinking through their philosophical reasoning I believe, would lead to the conclusions that government lacks jurisdiction over religious exercises, exercises as such. What does that mean? Well these are the key points: government can’t punish religious beliefs or exercises as such, they can’t prohibit religious beliefs or exercises, they can’t mandate religious beliefs or exercises as such, they can’t regulate religious beliefs as or exercises as such. As such is important, it means the state cannot directly target a religious exercise as a religious exercise. The state can’t outlaw specific religious exercises on account of it being a religious practice. But government can make generally applicable laws that incidentally apply to religious practices. So the state can make regulations concerning water quality, but it can’t make regulations for how a Catholic priest must bless the water so it becomes holy water. A state can make building regulations that apply to all buildings including houses of worship, it can’t dictate where in a church the altar must be placed, or in what directions the congregants must pray. The state can license professionals. Right? All of you want a law license. But it can’t license ministers, religious ministers. Government can’t make such laws about religious exercises as such, because we never gave it authority to. Right? It’s in the circle of our unalienated natural rights.

Okay, let me go back to the text of the First Amendment. At the beginning, again I’m following Justice Alito here starting with the text, I said a construction of the free exercise clause that is consistent with the text, must be about congress’s power, it’s law making power, and it must be categorical. This is how Justice Alito and the originalist [unintelligible], effectively interpret, the First Amendment. They read it as if it says Congress shall make no law, and the executive branch shall enforce no law, prohibiting or burdening the free exercise of religion. Unless the state is advancing a compelling state interest, using the least restrictive means possible. The exemption approach, Justice Alito’s approach to free exercise, is not directly, is not directed at Congress’s law making power. In practices it’s primarily directed against the executive’s execution of laws, in specific cases. And it’s not categorical, sometimes under his approach, government can violate religious free exercise. It can violate religious free exercise when it has a compelling reason to do so. The exemption construction of the free exercise clause cannot be squared with the actual text of the First Amendment. There is a great irony in Alito’s Fulton opinion. He stakes everything on the text, and the text obviously refutes his position. Okay, what about the inalienable natural rights approach I have sketched? Well it is directed at Congress, Congress’ lawmaking power. Right? Congress can’t make laws that target religious exercises as such. And it is categorical, Congress can never do that. The non-exemption approach fits the text.

What am I doing on time? Okay, just, should I stop here? I have a few more things.

Five minutes maybe?

Two minutes.

Two minutes, two minutes perfect.

Three minutes, okay.

Take your time.

Three thoughts, three concluding thoughts: just things I wanted to place, in that we might talk about if you want, that I don’t have time to develop. First, I mean you probably know this already, almost all originalists disagree with me, right? Professor Yoo and I had an exchange where Professor Yoo, you know states why he thinks I’m wrong. I’ve only presented part of the evidence, but the evidence that follows Alito’s opinion, on on the, from the text. I think I presented the decisive evidence, but there’s more, much more to be said, including going through the drafting record. Okay secondly, I think the underlying reason that most originalists misinterpret the free exercise clause is that they misunderstand the work that the free exercise clause was meant to do. And maybe this is, in a way, one of the most interesting things to think about. Most originalists think the purpose of the First Amendment is to protect as much religiously motivated behavior as possible. Religious free exercise is like liberal autonomy for religious people. It’s defining religion however you want to define it and then to live accordingly. And this is why exemptionism, you might recall, was originally a doctrine of the left. The author of the exemptionist approach is William Brennan. The originalist author of the exemption approach is Michael McConnell. Michael McConnell clerked for William Brennan. The underlying purpose, at least the original underlying purpose of the free exercise clause however, was not to grant autonomy for religious people. It was to state explicitly that government had no authority to prescribe forms of worship, prescribe or proscribe. Now that seems extraordinarily narrow from our point of view, and in a sense it is. But in the course of human history, that teaching was revolutionary. It’s revolutionary to say those who govern cannot use the coercive force of law to prescribe correct forms of worship. We forget how revolutionary the founders constitutionalism is. Okay, with that, one last thought. Whether we should adopt the original purposes of the First Amendment and thus apply the Founders’ original understanding of religious free exercise, I think is an open question and there are lots of good reasons, which I presume a Federalist Society audience knows, on why we might follow originalism. But there are lots of interesting reasons, including conservative reasons, why we might depart from the Founders. But my task today, was simply to explain as best I can, what the original meaning of free exercise is. Um, I’d certainly be delighted to hear all your criticisms to that approach, and I’m especially interested in hearing what Professor Farber has to say. Thank you very much.

[DANIEL FARBER] I would like to say a few things. One is, that I found a lot to like about this book. For one thing, the tone is sort of a welcome relief from a lot of writing about constitutional history, which is just, you know, the um, dominated by a sense of absolute certainty about the correctness of the author’s view. The, the um, the utter bankruptcy of any opposing view, often being very selective about what evidence is chosen to discuss. And also, I think refreshing in that he doesn’t think that a quick look at one dictionary from the time period is enough to tell us what people in the 1790s thought. And any more than we can solve most legal disputes today, by just looking at the latest edition of the dictionary to see, and then conclude, that all of us must have agreed in our understanding of the text.

I want to talk a little bit about however about how I think some aspects of the book illustrate some of the problems with originalism, and then a little bit about the exemption issue itself. I’m um, I’m probably closer to Justice Barrett at this point than I am to the other members of the court, in the Fulton case.

Um, so in terms of originalism, members of this audience may know that, but I think most people have a sort of simple idea that originalism is about the original intent. And originalism may have started out that way, but it’s evolved a lot, and now has a whole bunch of different schools of thought within it that make it very difficult to actually argue with originalism because you, you know, whatever form of originalism you criticize, that you’re likely to be met by the argument that that’s not real originalism, the real originalism is something else.

One of the things I like about the book, partly because I’m just interested in history for its own sake, is the effort to sort of contextualize the, the um, free exercise clause within both the sort of intellectual world of the late 18th century, uh, and within you know, some of the live disputes that might have motivated people to think they needed to have a free exercise clause. So really, put it in the context of history. But I think it’s very difficult exactly to characterize, um, uh, how, uh, this fits or doesn’t fit with particular forms of originalism. Originalism today is no longer really about the intent of the framers, it’s about the understanding of the reasonable reader. The reasonable person of the 18th century reading the text of the Constitution, at least that’s what most originalists now think. Well, as law students you may remember from torts, that the reasonable person is kind of a slippery character. It can be very difficult to characterize exactly what the reasonable reader knows, a reasonable person knows and didn’t know, and how they would view any given situation. And I think that’s one of the reasons for the sort of fragmenting of originalism today, is this effort to try to figure out you know, who’s the reasonable reader, and to escape from the allegation that when people talk about the reasonable 18th century reader, they’re really looking in the mirror. Because, who could be more reasonable than they are themselves?

So, I have to say, the Supreme Court seems relatively oblivious to these disputes. I think just I think Justice Alito’s claim to be an originalist is actually, quite suspect. Not only because of this case, but also because in other cases he’s come out in favor of something called history and tradition, that seems to involve the original understanding, but then sort of slide over into some more amorphous sense of what, you know, American history or something. Um, however, not for me to decide, who counts as an orthodox originalist and who doesn’t. Um, so one of the issues I’ve seen with originalism, really from almost the first time I started doing work in this area which was, research on the original meaning of the 14th Amendment, a long time ago, is that there’s kind of a conflict. Because, the more we try to understand, it’s like we’re trying to put ourselves somehow into the shoes of somebody from the late 18th century. And, the more we simplify that task by say just looking at dictionaries or whatever, the less we’re really being true to their world and their point of view. But, the more that we try to really wear their shoes, the more we realize, that they don’t fit, that we actually are not late 18th century Americans and that it’s very difficult to um, sort of navigate the translation from the way they thought to the way we think today. And I think the book illustrates that to some extent. So, I’ll just talk briefly about a couple of ways where I saw that as problematic.

One is this issue of natural rights and inalienable rights and I think the fact that Professor Munoz had to speak, had to lay that out so carefully, and clearly, is also a sign that it’s not really very familiar to people today. Right? This, people I think still have some idea, I think the human rights movement for example, internationally, has sort of founded on some kind of general sense that there are innate rights. But, but, it’s it’s it’s, really kind of an intuition, it’s not part of this intellectual framework, um, I guess in modern philosophy it’s closer to the view of John’s, John Rawls, um, in his theory of justice, which is very social compact oriented. But, it’s very um, uh you know, it’s just not our lingo today, it’s not our way of thinking and we have to really make an effort to try to think that way. A similar point um, it goes more specifically to the reconstruction of the framers views, Professor Munoz says that um, let me see if I can get this. Um uh, so uh, he characterizes the right is as rooted in not only the right, but the duty of individuals, to freely worship their creator. Um, and expresses that in terms of duties to God and the moral fabric of the human nature, of which they understood. Uh, with God as the author of human nature. Um so, one problem here is that the Framers, according to Professor Munoz, but I I believe him, thought that this was a natural duty or a natural right, in the sense that you don’t need any revelation to know about God and the duty of humans to worship God. You can look, you can deduce it, really, from looking at nature. I think that’s a minority belief these days. It certainly is at home with some strands within Catholic thinking, I think a fair number of Protestants would reject it and insist on revelation as being the critical element in any form of religious knowledge, and of course secularists reject it for other reasons. Um so, so again we have to stretch a little bit to, to reach that. this conclusion today I think, and to try to think about why somebody a couple hundred years ago would have thought this. Um, it also seems to me that this leads to a narrower view of religion than we have today. The idea that Professor Munoz says that the theory is to be defined narrowly and does not include beliefs and practices divorced from the conception of a creator God. Well, that fits everybody in a society that is predominantly Christian, with a few Jews, and more generally, a society where the world monotheistic religions are dominant. But that’s not everybody, right? Um, there are polytheistic religions where there might have been a Creator at some point, it’s part of the story, but the religion is not necessarily focused on the creator god, that in some cases a creator god might not even, you know, may be dead, or transformed. I looked up to find out who created humans in the, in Greek classical religion, and learned that Prometheus molded the clay and Athena blew in the breath. But Prometheus wasn’t a god at all, really. And Athena, although a significant God, was not the most important, you know was was a second tier God under Zeus. And so I don’t really know how this fits with those with Hinduism for example, um I’m not sure, there are forms of Buddhism where I think the Creator really doesn’t really figure, and I don’t know how it fits with Native American religions either. And that’s, I think, that might or might not have been a problem from the point of view of the framers, but it’s a problem for us because we live in a society that is more diverse, where we have more people who don’t fit um the kinds of religious practices the framers were thinking of. Um so I guess I’d say, um, I think this, this, illustrates attention about originalism, the more we try to be true to the framers, the harder it is for us to really imagine ourselves uh, bound by their thinking, because it’s foreign to the way we think about things today.

Let me switch, and just talk quickly about Fulton. Um, so full, as you probably know if, well, or, you may not since we don’t cover uh the First Amendment in the con-law course. Uh, basic con-law course, uh the Supreme Court uh, in a case called Smith written by Justice Scalia, said that law, that there is no right to a religious exemption from general law, law laws, [unintelligible] you know general application. So for example, in that case it was a ban on peyote, and [unintelligible], and Scalia said there’s no right to an exemption, even if you’re a Native American who abused peyote as part of uh, religious ritual. However there are a couple of exceptions uh that Scalia wrote into the opinion. The exceptions have proved very troublesome and somewhat difficult to apply, which is one of the arguments that maybe Smith needs to be rethought. I’m somewhat torn. Justice Barrett said that although she didn’t really see it original, that there was a clear originalist case for exemptions, um, that she thought at least, by in parallel to some of the other First Amendment rights, that maybe, uh, even purely neutral laws could be challenged in cases where they burden religious practice, but that she wasn’t sure what the test should be. And I find, I think I’m in a somewhat similar position. At least I see an argument for why exemptions would be a good idea, remember I’m not an originalist, so I’m not not totally tied up in what the Framers thought. On the other hand I think that, in today’s society, administering a system of exemption is going to be very difficult. Partly because, partly because, at the time say Justice Brennan came up with this idea, there really only a small few small pretty well established religious groups who posed problems. And a lot of it was about things like working on Sunday or working on Saturday. We have a sort of, more, conflicts between religious views and secular laws, right that’s part of the culture wars. Um, and we also have more diverse religious views, so let me just give a quick example of of why I think this is going to be a hard line to to um, to navigate.

There are a couple of interesting lawsuits that have been filed in the aftermath of Dobbs, the um, case of a ruling Row versus Wade. And in these suits, women, I think predominantly Jewish women, but some Muslim women, have argued that their religion imposes a duty on them under some circumstances to get an abortion. Because it requires them to prioritize their responsibilities toward their spouses and their living children, and and does not classify fetuses as being part of that family unit until birth. Okay, so the argument is that they should get a religious exemption from various abortion restrictions. I think that’s illustrates some of the problems here right, I would expect that many of these women, are probably also opposed to abortion bans for a variety of other reasons that aren’t so religious. So uh, how do we, you know, how central does the religious view have to be in motivating the conduct? And that’s true in other cases too, right? Cases where people don’t want to um, uh, I don’t know, put something on a cake about a gay marriage. Maybe religious, but there are also people who are probably politically opposed uh, to gay marriage as well. So, how, you know, what does it have to be the main motive, religious? Any part of the motive? A but for a cause? We don’t know. Um, how sincere is religious belief? And I think providing a really robust set of exemptions is likely to produce a lot of those questions because there’s a big incentive to discover that you have a religious belief. Right? And, I’m so I’m old enough to remember the draft, and um, there was actually, I think they’re still around, it’s called The Universal Life Church and all you had to do is ask them and they would give you a certificate making you a minister of the church. Right. I don’t know how well that actually went over with draft board, it’s probably not that well, but I think we’re going to have, you know, maybe stuff that’s not quite that opportunistic looking, but, but you know, but people, there will be rewards for people who can find, you know, who have religions that say, support their political views, or their self-interest in other ways. So the sincerity issue I think is going to get trickier, the courts tried to dodge it by saying we have to presume sincerity, and we really shouldn’t question. But again, that’s going to get harder the more the realm of the cases expands, and what counts as a compelling interest? Is preserving fetal life a compelling interest? Is it a compelling interest all the way through pregnancy? Is that a compelling, are there um, is it a compelling interest in cases of rape or incest? Etc. Etc. It’s one of the reasons I think the Supreme Court overruled Roe v Wade, was to avoid those questions. But they could come back again in these exemption cases.

So, I think we’re kind of, I’m sort of torn, between the idea that I don’t like the idea of putting people to a choice between their deepest most sort of fundamental identity and compliance with the law, if it’s not really important for us to insist. But on the other hand, I see a lot of problems in making exemptions work. So I guess, if I had to I would opt for a regime that treats free exercise exemptions the way we treat First Amendment exemption. Right? Where normally there’s no problem if a state uh bans littering but if you arrest someone because they were handing out pamphlets that other people threw away and that’s littering, uh, then that file is free speech. I could see something along those lines but, but I’m not sure beyond that. And anyway, you’re not here to listen to my views, you’re here to listen to Professor Munoz so let me get off now.

[Applause]

Do you want to give a brief response to anything he said, or?

[MUNOZ] Well let me just very brief, um, I mean there was a an irony about the point about our religious diversity increasing, and then, I mean, if I understood the argument, our religious diversity is increasing therefore perhaps, the Founder’s natural rights thinking is less relevant today. I mean the irony is that the founders thinking about natural rights is how we limit government, and we say government can’t do certain things regarding religion, so in a way you think that’s even more relevant given our increased religious diversity today. To say that the founders natural rights thinking isn’t relevant would then suggest well we don’t really have inalienable natural rights meaning everything is subject to governmental power. And that that argument strikes me, that’s an odd argument to say that the Founders aren’t relevant. Uh, it would mean government can do more vis-a-vis religion, and we have more religious diversity so I actually think the argument for increased religious diversity pushes the other way. But that’s a that’s a small point.

[HAYWARD] I’ve got a couple of possible questions but we’re under 10 minutes. I want to see if there’s any questions from the audience for either of our figure, yeah go ahead.

[AUDIENCE] Can I ask how how you would deal with the problem that you can define any um, any law burdening religion in a way, frame it in a way that’s generally applicable. Um, so for example, if I wanted to, if I was the government and I wanted to ban communion, I could just ban all alcohol, in general.

[MUNOZ] Yeah, yeah, I know, but here’s the thing: You’d actually have a hard time passing a law that would ban all alcohol. It turns out, I mean the the example here, is the Santeria case. So this 1993, a church of the [unintelligible] Lukumi Babalu Aye. In this, this Santeria group, I mean they actually said we want to come out of the shadows, there’s 50 000 of us, we practice Santeria, and we don’t want to be hidden anymore. And they wanted to open a school, and have a museum, and all this. And this city outside of Miami freaked out. Like, we don’t want these guys in our town. And they tried to ban Santeria. So they, so they you know, passed a, Santeria practices animal sacrifice. So they passed a law banning animal sacrifice, and then they just realized, they made a whole bunch of legitimate businesses illegal in the town. And so then they had to keep on narrowing and narrowing until they banned ritualistic sacrifices, which was clearly targeted at the Santeria religion. So actually, the general applicability in practice, as your example actually shows, is a restraint. Because, well, most people wouldn’t want alcohol banned. And it turns out a lot of religion, religious interests that are part of what we do alienate to the government, are protected by general applicability. James Madison in Federalist 57 says, the surest way to have good laws is that the laws are applied against the lawmakers and the lawmakers friends. That’s his way of talking about general applicability. You apply the law to everyone, that is the surest check against having partial and unjust laws.

[HAYWARD] It, it is, it’s worth them noting as a historical matter, that you go back to Prohibition 100 years ago, and communion wine was exempted from the prohibition. Which is why clever drinkers always went through the communion line four or five times every Sunday.

[MUNOZ] No, no, I mean, I’m being presumptuous here, but I think we can all assume, I hope we can all agree that you know prohibition violated the natural law in every sense of decency and justice. [unintelligible] And you never would have got it passed, if you had not exempted Catholics and church wine which is interesting to think about, it’s the exemptions that facilitated the passing of this terrible law. No exemptions, no law.

[HAYWARD] Well that’s why I always repair to Will Rogers great observation, at least prohibition is better than no liquor at all. [unintelligible]

[AUDIENCE] So we’ve construed inalienable uh and we construed natural rights, but we haven’t construed worship, and we haven’t construed worship as such, and uh, in particular, we haven’t gone to um, might you might, maybe a corpus linguistics approach of the literature of the time, what does worship as such mean and is that expansive of the various acts following whichever diety you prefer, um or is it only taking communion and participating in the sacramental aspects of religion?

[MUNOZ] Yeah, you know tell me your name.

[AUDIENCE] Jim.

[MUNOZ] Jim, that’s a terrific question, and that’s that’s exactly the the next question that one should ask on this. So what is, so what is it in the category of inalienable rights, what what consists of that? Um so the way we’d figure it out, is it’s um it’s ontological, it’s not, it’s moral realism. Like there is a substance of things that are religious exercises by nature. So, meaning, we don’t define it as whatever the believer or practitioner says is religious, is religious. If we go down that direction whatever the religious believer says is religious is protected, we’re going to get exactly the questions that Professor Farber, you know is religion for religious reasons, I must get an abortion. That’s naturally where that, so so how do we go about doing it? Well the first thing we have to think about is well, what what are the things we alienate to government, what can government legitimately do? Right? think of the the two circles. And things that where government can legitimately do it, are not part of what’s not alienated. And you could do corpus linguistics, you can just think about it, you’d have to um, if you pressed me, I’d say you’re going to end up talking about things that are consistent with reason, but above reason. Right, so practices or beliefs can be irrational, they can be rational, and they can be super rational. And it’s the practices that are super rational, above reason but not contrary to reason, it’s the realm of what’s not alienated. Now, what exactly that is, is a long discussion. I’d say let’s go to the fourth book of the essay concerning human understanding, and it’s going to take work. Or the alternative is, we do it as lawyers do, case by case, and we develop you know, this is what the law actually does, and you’re going to be able to say well let’s start from the simple cases and if we can rash reason from the simple cases then we can go to more difficult cases, and we can make real distinctions.

[HAYWARD] Let me try, unless someone, can I try a hypothetical on that point that takes us from theory down to practice, unless someone else wants to follow on on this line or something new? I don’t, I was going to give students the opportunity ahead of me. All right uh, look um, we work from the uh, what do you how did you just put it there at the end? We work from you know clear cases down to harder cases. I mean we wouldn’t have trouble uh prescribing a religion that wanted to bring back human sacrifice, which was practiced until not that many centuries ago.

All right, let’s try something different, uh, we have the Americans with Disabilities Act, suppose a, and so you know we’re building codes you’ve got to conform to, suppose a denomination comes along, and they’re a faith-healing church. And their claim is, we don’t want any wheelchair ramps outside or inside the church, up to the altar, or even getting in the front of the building, because, because it – it contradicts uh, and by the way, Christian Science Doctrine strictly applied things that I don’t want to be crass and say it’s on your head, but you get the point. A faith healer could say, it’s against our faith to have a visible symbol that contradicts and undermines the faith people need to have to be healed by God’s grace. Therefore, we want an exemption from ADA requirements for wheelchair ramps. What does Justice Munoz say about that? That’s I mean that’s easy though, do we, does government have the power to institute building codes? Is that a legitimate use of government power? Well, then you’d have to go through the argument, why do we have building codes? To protect people, and if if the government has that power, government can, has has that power. And it’s that, I need the circles up there, that’s within the circle. The free exercise clause is not meant to protect realms of activity within that circle of what we’ve given to government. Now a town or a state could give an exemption as a sort of legislative grace. I mean, that’s what happens with the Quakers at the time of the [unintelligible] we won’t make you fight, you can wash dishes or something else, but there’s no constitutional right. The church could make an argument on why building codes or ADA ramps are a bad idea for everyone, but that’s what living in a self-governing republican government is. We give government to make building codes, they can make building codes everyone has to live by the building codes. We can grant discretionary exemptions, there’s no right to be exempt from a generally applicable, I’m sorry no right to be exempt from an otherwise valid law. Full stop. That’s not the work of the free exercise clause, the free exercise clause and the first amendment is not meant to rid the world of laws that religious people don’t like and find burdensome. I mean that is the fundamental mistake lawyers make, you think the Constitution is meant to remedy all evil. And take your particular evil and take your particular clause, and you say well, whatever evil there is in the world, I’m going to rid it through my interpretation of equal protection, or due process, or in the cases of religious people, the free exercise clause. That’s a different type of jurisprudence but that’s not originalism.

[AUDIENCE] We’re on time, but you mentioned the Quakers again, doesn’t that seem to fit into your inalienable pack for it, because you’ve already established that you can’t create new exemptions on the basis of religion.

[MUNOZ] Well you can do them legislatively. But look, what, what is the political community? The most the most basic thing of the political community is, is a mutual defense pact: I won’t harm you, you don’t harm me, we fight together against our enemies. That is the most basic thing a political community is. And the Quakers want to say we, want to be part of the club but we don’t want to fight, it’s actually a non-sensible position. Right? And that, no, we’re a fight club. That’s what a political community is. And if you want to be a part of the club now, we might have you do something else, but your real natural right is to not be part of the community if you don’t agree to its terms.

[HAYWARD] Unfortunately this isn’t the NFL we can’t go into overtime for the Kansas City Chiefs win thank you thank you very much professor

[Applause]

[Music]