August 14 – September 20, 2008

University of California, Berkeley, School of Law

In fall 2007, the Robbins Collection acquired one of the 799 limited edition copies of the Processus Contra Templarios, a facsimile reproduction of the parchments containing the minutes of the 14th-century trial under Pope Clement V against the order of the Knights Templar; this served as a centerpiece for the Robbins Collection’s Fall 2008 exhibit.

In fall 2007, the Robbins Collection acquired one of the 799 limited edition copies of the Processus Contra Templarios, a facsimile reproduction of the parchments containing the minutes of the 14th-century trial under Pope Clement V against the order of the Knights Templar; this served as a centerpiece for the Robbins Collection’s Fall 2008 exhibit.

Inspired by the vivid afterlife the Knights Templar—their order, their rituals, their persecution—have had in the popular imagination, this exhibit presented three historic trials as they were formally documented at the time and as they have continued to be represented and interpreted in the centuries since. Different in scope— from the trial of a wealthy and powerful medieval organization, the Knights Templar, to the far-reaching trend of persecution in communities from Early Modern Europe to Colonial America that culminated in the Salem Witch Trials, to a trial to prove (or disprove) the identity of a single individual, Martin Guerre—each of these three trials was a sensational legal drama that had at its heart issues of power and control, whether political, social, or communal.

The religious mysticism and secrecy surrounding the Knights Templar, the accusations of sorcery and witchcraft leveled against ordinary townspeople during the witch trials; or the family drama, intrigue, and questions of memory and identity in Martin Guerre story—what ties these trials together is the manner in which they have each captured people’s imaginations for centuries, giving rise not only to a wealth of scholarship, but becoming part of popular culture in the form of paintings, novels, plays, and films.

Legal Basis for Witch Trials

Historians have identified a number of crucial legal developments that led to the panic surrounding— and subsequent trials of— witches in Early Modern Europe. One was the idea of “heretical fact,” put forth by Pope John XXII (1316-1334), which allowed heresy to be viewed as a deed and not just an intellectual crime. Another step was the establishment of a link between witchcraft and heresy, a link that had not existed before the end of the 15th century, which emerged thanks to a new theory of “diabolical witchcraft” that held that the practice of malefice (such as using religious objects to curse one’s neighbor) in fact involved an active pact with the Devil and was therefore a heretical act and not just a ritual performed by misguided country folk. This view of witchcraft was spread throughout Europe by handbooks like the Malleus Maleficarum.

Ugolini, Zanchino. Tractatus nouus aureus et solemnis de haereticis…Venetijs: Ad Candentis Salamandrae Insigne, 1571.

Malleus Maleficarum

The height of the German witch frenzy was marked by the publication of the Malleus Maleficarum (“Hammer of Witches”), a book that became the handbook for witch hunters and Inquisitors. Written in 1486 by Dominicans Heinricus Institoris and Jacobus Sprenge, and first published in Germany in 1487, the main purpose of the Malleus was to systematically refute arguments claiming that witchcraft did not exist, to refute those who expressed skepticism about its reality, to prove that witches were more often women than men, and to educate magistrates on the procedures that could find them out and convict them. The main body of the Malleus text is divided into three parts; part one demonstrates the theoretical reality of sorcery; part two is divided into two distinct sections, or “questions,” which detail the practice of sorcery and its cures; part three describes the legal procedure to be used in the prosecution of witches. The Malleus was republished 26 times in the Early Modern period and remained a standard text on witchcraft for centuries.

Malleus maleficarum. Francofurti: Sumptibus Nicolai Bassaei, 1588

Legal and Geographical Discrepancies in European Witch Trials

Differences in the development of legal systems in Early Modern Europe had a profound influence on the course the witch trials took in different countries. The relatively few prosecutions of witches in Spain, Italy, and France, for example, can be attributed to the fact that neither the Spanish nor the Roman inquisition believed that witchcraft could be proven. England likewise saw relatively few prosecutions due to the checks and balances inherent in the jury system. It was only in places like Scotland, the Alpine lands, and in South German ecclesiastical principalities that witch panics and actual prosecutions proliferated. In those regions, made up of small, weak states, secular courts actively and successfully prosecuted heresy cases. Another important reason for the active conviction of witches in the German states was the Holy Roman Empire’s adoption of the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina in 1530, which not only instituted prosecution at the judge’s initiative, thus putting the accused witches at the mercy of a magistrate who was at once judge, investigator, prosecutor, and defense counsel, but also provided for the secret interrogation of the accused, denied him or her counsel, required torture in order to extract a confession, and specified that witches be punished with death by burning.

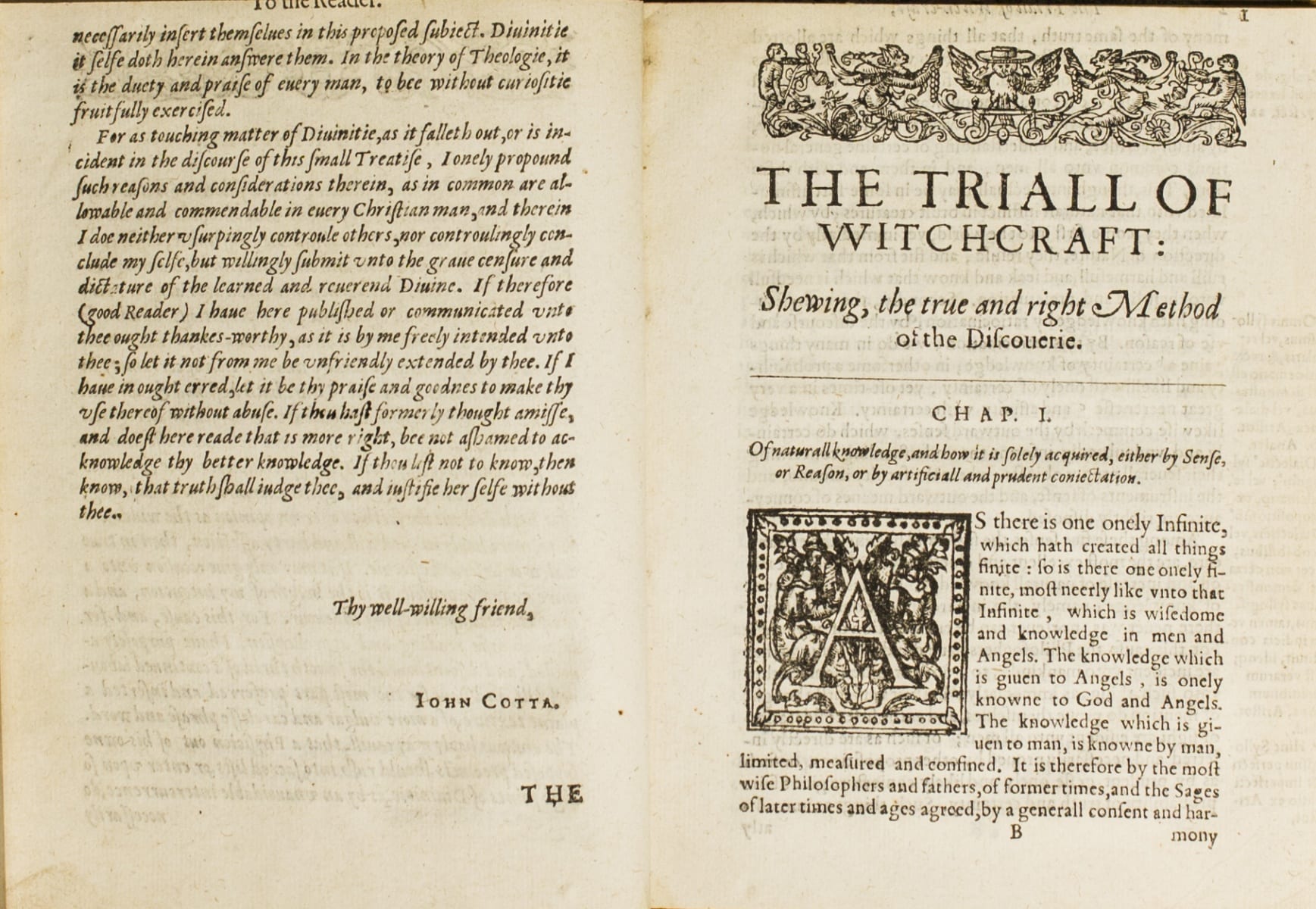

Cotta, John, 1575(?)-1650(?). The triall of witch-craft…London: Printed by George Purslowe for Samuel Rand, and are to be solde at his shop neere Holburne-Birdge, 1616

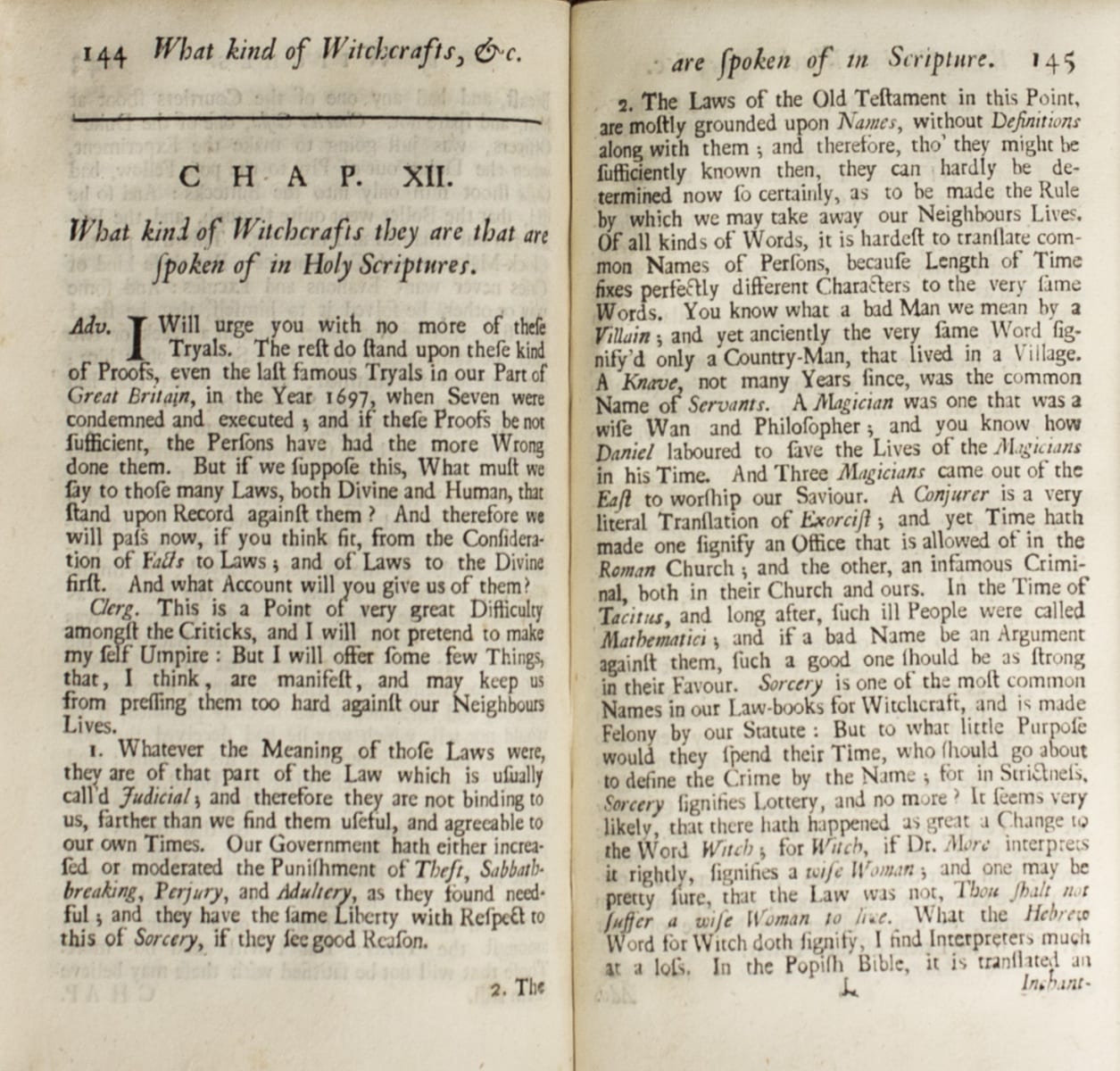

Hutchinson, Francis, 1660-1739. An historical essay concerning witchcraft…London: Printed for R. Knaplock…and D. Midwinter…1718

Witch Hunts in Early Modern Europe

The height of the witch hunting frenzy in Early Modern Europe came in two waves: The first wave occurred in the 15th and early 16th centuries, the second wave in the 17th century. Witch hunts were seen across all of Early Modern Europe, but the most significant area of witch hunting is considered to be southwestern Germany, where the highest concentration of witch trials occurred during the years 1561 to 1670.

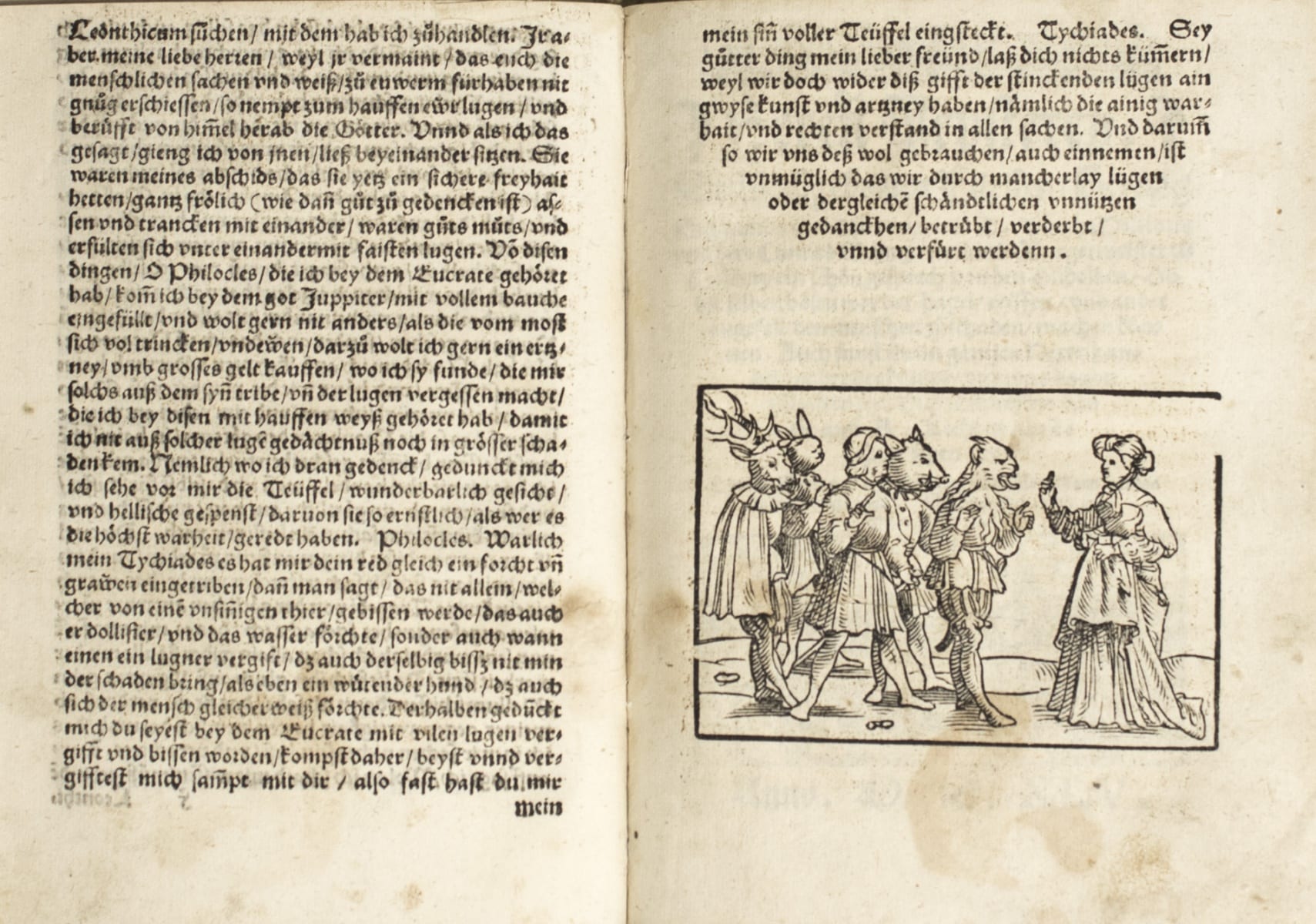

Molitor, Ulrich. Hexen Meysterey…Strasbourg(?): J. Cammerlander(?), 1545

Salem Witch Trials: Beginnings

The 1692-1693 Salem Witch Trials were a brief outburst of witch hysteria in the New World at a time when the practice was already waning in Europe. In February 1692 a girl became ill, and at the same time her playmates also exhibited unusual behavior. When a local doctor was unable to cure the girls, a supernatural cause was suggested and suspicions of witchcraft emerged. Soon three townswomen were accused of witchcraft: Tituba, a slave, Sarah Good, a poor beggar and social misfit, and Sarah Osborne, a quarrelsome woman who rarely attended church. While the matter might have ended there with the three unpopular women serving as scapegoats, during the trial Tituba— possibly to avoid being unfairly prosecuted— declared she was a witch and that she and the other accused women flew through the air on poles. With skeptics silenced, witch hunting began in earnest.

Court of Oyer and Terminer

Before long, accusations of witchcraft abounded and the jails filled with suspects who confessed to witchcraft, seeing it as a means to avoid hanging. The provincial governor created court of “oyer and terminer” which allowed judges to hear “spectral evidence” (testimony by victims that the accused witch’s specter had visited them) and granted ministers with no legal training authority to guide judges. Evidence that would be disallowed today— hearsay, gossip, unsupported assertions— was routinely admitted, while defendants had no right to counsel or appeal. Through the rest of 1692, in a climate of fear, accusations flew, many were convicted, and a number were put to death.

Decline and Closure of Salem Witch Trials

By the fall of 1692 the witch hunting hysteria began to die down as more and more people began to doubt that so many people could be guilty of witchcraft. People urged the courts not to admit spectral evidence and to rely instead on clear and convincing testimony. Once spectral evidence was no longer admissible, acquittals abounded, and the three originally convicted women were pardoned. In May of 1693 the remaining accused and convicted witches were released from prison. Over the course of the Salem witch hysteria, of the 150 people who were arrested and the 26 who were convicted, 14 women and 5 men were executed. The Salem Witch Trials only lasted a little over a year and had very little practical impact on the Colonies at large. However, the trials and executions had a vivid afterlife in the American consciousness, giving rise to a wealth of scholarship and an abundance of cultural artifacts including paintings, novels, plays, and films.

The Martin Guerre Story

In 1548, a French peasant named Martin Guerre disappeared from his village in Artigat, abandoning his wife Bertrande and their son. Eight years later a man appeared claiming to be Guerre. His physical appearance and detailed knowledge of Guerre’s life convinced villagers as well as the Guerres that he was the true Martin. The “new” Martin lived for three years with Bertrande and her son and had two children by her. He claimed inheritance to the Guerre’s dead father and even sued his uncle, Pierre Guerre, for part of the inheritance. In the ensuing dispute, Pierre became suspicious of the new Martin. A soldier passing through the village claimed the new Martin was an impostor and that the real Martin had lost his leg in the war after leaving Artigat. The new Martin was accused of imposture, but Bertrande maintained his claim, and he was acquitted in the local court.

Pierre Guerre was not satisfied, believing the new Martin to be Arnaud du Tilh, a man of questionable reputation from a neighboring village, and initiated a new case by falsely claiming to act for Bertrande. After hearing more than 150 witnesses, with many recognizing Martin Guerre (including his four sisters), many recognizing Arnaud du Tilh, and many refusing to take sides, the court in Rieux found the accused guilty as charged. He appealed to the Parlement of Toulouse, whose judges were mesmerized by the prodigious abilities of the alleged imposter to recall decades’ worth of facts and intimate details from the life of Martin Guerre. In 1560 the parlement judges were poised to overturn the guilty charge when the stunning reappearance of the real Martin Guerre ended the trial, whereupon the imposter du Tilh was sentenced to death for his crimes of adultery and imposture.

Legal Impact of the Martin Guerre Case

One of the Toulouse judges was the distinguished civil law jurist Jean de Coras, who published numerous scholarly treatises on law. Charge with producing the official report of the trial, Coras was so fascinated with the evolving drama of the Guerre case, and the legal problems it posed that he published a full account in 1561 that became wildly popular, with five reprintings in roughly as many years and new editions produced over the next two decades in Paris, Brussels, and Frankfurt. The case was of primary interest to lawyers and judges, presenting as it did a legal problem with little established precedent: how to judge a rather novel crime, imposture, in circumstances that tested the conventional limits of evidence and proof. How did one definitively prove one’s identity in an age before physical evidence such as fingerprints or dental records? What role did memory play when the “memories” of an imposter could be so thoroughly substantiated by communal memory and eyewitness testimony? The Guerre case wove an intricate web that incorporated legal issues of impersonation, fraud, marriage, adultery, and inheritance, and provoked fundamental communal, social, and juridical questions about the nature of individual identity.

Martine Guerre and the Popular Imagination

Jean de Coras was not the only contemporary chronicler of the case. Attesting to the sensational interest in the story at the time, a second account of the trial was published by Guillaume Le Sueur under the title Histoire Admirable. Nor was interest limited to the legal community. The Guerre story, with its salacious details of marital intimacy and collusion, family drama and intrigue, and the sheer audacity of its protagonist, captured the popular imagination not for decades, but for centuries to come. From being recounted with its original cast of characters in the 17th– and 18th-century collection of histoires prodigieuses and causes célèbres, to being respun in different places and times, the Martin Guerre story has been told time and again. It received attention from many illustrious storytellers of the early modern period, such as the 17th-century Spanish playwright Lope de Vega and 18th-century French social commentator Montesquieu, who based one of his Persian Letters, it has been recently speculated, on the Guerre story. Alexandre Dumas included a fictionalized version of the story in his novel the Two Dianas as well as in his multi-volume Celebrated Crimes. Interest in the story has continued into the 20th century in the form of plays, novels, and films. The 1982 film Le Retour de Martin Guerre, starring Gerard Depardieu, remains mostly true to the original historical account, repopularized by the historian Natalie Zemon Davis and her book, The Return of Martin Guerre. The 1993 film Sommersby, starring Richard Gere and Jodie Foster, more fancifully recast the story in the American Civil War era.