We have commissioned nationwide, telephonic (wireline and wireless) survey research to elucidate consumer attitudes toward information privacy

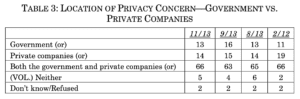

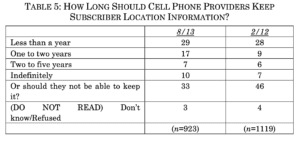

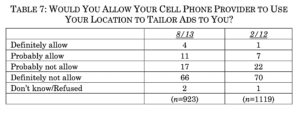

Alan Westin’s Privacy Homo EconomicusChris Jay Hoofnagle and Jennifer M. UrbanCite as: Chris Jay Hoofnagle and Jennifer M. Urban, Alan Westin’s Privacy Homo Economicus, 49 Wake Forest Law Review 261 (2014), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2434800 This article is a capstone to our years of survey research work. We summarize our different surveys and situate our findings in the theoretical framework developed by Professor Alan Westin. Homo economicus reliably makes an appearance in regulatory debates concerning information privacy. Under the still-dominant U.S. “notice and choice” approach to consumer information privacy, the rational consumer is expected to negotiate for privacy protection by reading privacy policies and selecting services consistent with her preferences. A longstanding model for predicting these preferences is Professor Alan Westin’s well-known segmentation of consumers into “privacy pragmatists,” “privacy fundamentalists,” and “privacy unconcerned.” To be tenable as a protection for consumer interest, “notice and choice” requires homo economicus to be broadly reliable as a model. Consumers behaving according to the model will know what they want and how to get it in the marketplace, limiting regulatory approaches to information privacy. While notice and choice is undergoing strong theoretical, empirical, and political critique, U.S. Internet privacy law largely reflects these assumptions. This Article contributes to the ongoing debate about notice and choice in two main ways. First, we consider the legacy Westin’s privacy segmentation model itself, which as greatly influenced the development of the notice-and-choice regime. Second, we report on original survey research, collected over four years, exploring Americans’ knowledge, preferences, and attitudes about a wide variety of data practices in online and mobile markets. Using these methods, we engage in considered textual analysis, empirical testing, and critique of Westin’s segmentation model. Our work both calls into question longstanding assumptions used by Westin and lends new insight into consumers’ privacy knowledge and preferences. A close textual look at factual and theoretical assumptions embedded in the segmentation model shows foundational flaws. With testing, we find that the segmentation model lacks validity in important dimensions. In analyzing data from nationwide, telephonic surveys of Internet and mobile phone users, we find an apparent knowledge gap among consumers concerning business practices and legal protections for privacy, calling into question Westin’s conclusion that a majority of consumers act pragmatically. We further find that those categorized as “privacy pragmatists” act differently from Westin’s model when directly presented with the value exchange — and thus the privacy tradeoff — offered with these services. These findings reframe the privacy pragmatist and call her influential status in U.S. research, industry practice, and policy into serious question. Under the new view, she cannot be seen as “pragmatic” at all, but rather as a consumer making choices in the marketplace with substantial deficits in her understanding of business practices. This likewise calls into question policy decisions based on the segmentation model and its assumptions. We conclude that updated research and a policy approach that addresses both rationality and knowledge gaps are key. Sample tables– Table 3: Are you “more concerned about the collection and use of information by the government, by private companies, or by both the government and private companies?” Table 5: How long wireless service providers should retain the location data they collect about wireless phones on their network? Table 7: Would you definitely allow, probably allow, probably not allow, or definitely not allow your cellphone service provider to use information about your location to tailor advertisements to you?

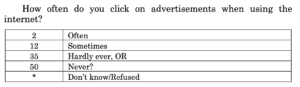

How often do you click on advertisements when using the internet? |

|

The Privacy Pragmatic as Privacy VulnerableJennifer M. Urban and Chris Jay HoofnagleCite as: Jennifer M. Urban and Chris Jay Hoofnagle, The Privacy Pragmatic as Privacy Vulnerable, Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security (SOUPS 2014) Workshop on Privacy Personas and Segmentation (PPS), July 9-11, 2014, Menlo Park, CA, https://ssrn.com/abstract=2514381 Alan Westin’s well-known and often-used privacy segmentation fails to describe privacy markets or consumer choices accurately. The segmentation divides survey respondents into “privacy fundamentalists,” “privacy pragmatists,” and the “privacy unconcerned.” It describes the average consumer as a “privacy pragmatist” who influences market offerings by weighing the costs and benefits of services and making choices consistent with his or her privacy preferences. Yet, Westin’s segmentation methods cannot establish that users are pragmatic in theory or in practice. Textual analysis reveals that the segmentation fails theoretically. Original survey data suggests that, in practice, most consumers are not aware of privacy rules and practices, and make decisions in the marketplace with a flawed, yet optimistic, perception of protections. Instead of acting as “privacy pragmatists,” consumers experience a marketplace myopia that causes them to believe that they need not engage in privacy analysis of products and services. Westin’s work has been used to justify a regulatory system where the burden of taking action to protect privacy rests on the very individuals who think it is already protected strongly by law. Our findings begin to suggest reasons behind both the growth of some information-intensive marketplace activities and some prominent examples of consumer backlash. Based on knowledge-testing and attitudinal survey work, we suggest that Westin’s approach actually segments two recognizable privacy groups: the “privacy resilient” and the “privacy vulnerable.” We then trace the contours of a more usable segmentation and consider whether privacy segmentations contribute usefully to political discourse on privacy. |

|

Privacy and Advertising MailChris Jay Hoofnagle, Jennifer Urban and Su LiCite as: Chris Jay Hoofnagle, Jennifer Urban and Su Li, Privacy and Advertising Mail, Dec. 3, 2012, available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=2183417. In this paper, we consider why Americans may frame the generation and receipt of unsolicited advertising mail as a privacy violation. We then present data from our nationwide survey showing that a very large majority of Americans, across all ideologies, educational attainment Figures from the report: |

|

Privacy and Modern Advertising: Most US Internet Users Want “Do Not Track” to Stop Collection of Data About their Online

|

|

Mobile Phones and PrivacyJennifer M. Urban, Chris Jay Hoofnagle and Su LiCite as: Jennifer M. Urban, Chris Jay Hoofnagle, and Su Li, Mobile Phones and Privacy, Jul. 11, 2012, available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=2103405. Mobile phones are a rich source of personal information about individuals. Both private and public sector actors seek to collect this information. Facebook, among other companies, recently ignited a controversy by collecting contact lists from users’ mobile phones via its mobile app. A recent Congressional investigation found that law enforcement agencies sought access to wireless phone records over one million times in 2011. As these developments receive greater attention in the media, a public policy debate has started concerning the collection and use of information by private and public actors. To inform this debate and to better understand Americans’ attitudes towards privacy in data generated by or stored on mobile phones, we commissioned a nationwide, telephonic (both wireline and wireless) survey of 1,200 households focusing upon mobile privacy issues. We found that Americans overwhelmingly consider information stored on their mobile phones to be private—at least as private as information stored on their home computers. They also overwhelmingly reject several types of data collection and use drawn from current business practices. Specifically, large majorities reject the collection of contact lists stored on the phone for the purposes of tailoring social network “friend” suggestions and providing coupons, the collection of location data for tailoring ads, and the use of wireless contact information for telemarketing, even where there is a business relationship between the consumer and merchant. Respondents evinced strong support for substantial limitations on the retention of wireless phone usage data. Respondents also thought that some prior court oversight is appropriate when police seek to search a wireless phone when arresting an individual. Figures from the report: Fig 1 – Is Mobile Phone Data as Private as Home Computer.jpg Fig 2 – Permission for Search During Arrest.jpg Fig 3 – Should Stores Call Mobile Phones.jpg Fig 4 – Can Apps Collect Contact List.jpg Fig 5 – How Long Should Location Data Be Kept.jpg Fig 6 – Can Cell Provider Use Location for Ads.jpg Fig 7 – Age Comparison – Is Mobile Phone Data as Private as Home Computer.jpg |

|

Mobile Payments: Consumer Benefits & New Privacy ConcernsChris Jay Hoofnagle, Jennifer M. Urban, and Su LiCite as: Chris Jay Hoofnagle, Jennifer M. Urban, and Su Li, Mobile Payments: Consumer Benefits & New Privacy Concerns (April 24, 2012), available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2045580. An abbreviated version of this report appears as, Jennifer M. Urban, Chris Jay Hoofnagle, and Su Li, Mobile Payments: Consumer Benefits & New Privacy Concerns, The European Financial Review p. 9, Feb/Mar. 2013. In October 2010, the Samuelson Clinic co-hosted a day-long conference on international perspectives on mobile payments, with a focus on consumer protection. The conference report is published as, Elizabeth Eraker, Colin Hector & Chris Hoofnagle, Mobile Payments: The Challenge of Protecting Consumers and Innovation, 10 PVLR 212 (Feb. 7, 2011) Payment systems that allow people to pay using their mobile phones are promised to reduce transaction fees, increase convenience, and enhance payment security. New mobile payment systems also are likely to make it easier for businesses to identify consumers, to collect more information about consumers, and to share more information about consumers’ purchases among more businesses. While many studies have reported security concerns as a barrier to adoption of mobile payment technologies, the privacy implications of these technologies have been under examined. To better understand Americans’ attitudes towards privacy in new transaction systems, we commissioned a nationwide, telephonic (wireline and wireless) survey of 1,200 households, focusing upon the ways that mobile payment systems are likely to share information about consumers’ We explain some advantages of mobile payment systems, some challenges to their adoption in the United States, and then turn to our main finding: Americans overwhelming reject mobile payment systems that track their movements or share identification information with retailers. We then suggest a possible remedy for such information sharing: adapting provisions of California’s Song-Beverly Credit Card Act, which prohibits merchants from requesting personal information at the register when a consumer pays with a credit card, to mobile payments systems. Our survey results suggest that consumers would support limitations on information collection and transfer. Song-Beverly could be adopted to accommodate those who wish to share their transaction data. |

|

How Different are Young Adults from Older Adults When it Comes to Information Privacy Attitudes and Policies?Chris Jay Hoofnagle, Jennifer King, Su Li, and Joseph TurowCite as: Chris Jay Hoofnagle et. al., How Different Are Young Adults from Older Adults When It Comes to Information Privacy Attitudes and Policies? (Apr. 14, 2010), available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=1589864. Media reports teem with stories of young people posting salacious photos online, writing about alcohol-fueled misdeeds on social networking sites, and publicizing other ill-considered escapades that may haunt them in the future. These anecdotes are interpreted as representing a generation-wide shift in attitude toward information privacy. Many commentators therefore claim that young people “are less concerned with maintaining privacy than older people are.” Surprisingly, though, few empirical investigations have explored the privacy attitudes of young adults. This report is among the first quantitative studies evaluating young adults’ attitudes. It demonstrates that the picture is more nuanced than portrayed in the popular media. In this telephonic (wireline and wireless) survey of internet using Americans (N=1000), we found that large percentages of young adults (those 18-24 years) are in harmony with older Americans regarding concerns about online privacy, norms, and policy suggestions. In several cases, there are no statistically significant differences between young adults and older age categories on these topics. Where there were differences, over half of the young adult-respondents did answer in the direction of older adults. There clearly is social significance in that large numbers of young adults agree with older Americans on issues of information privacy. A gap in privacy knowledge provides one explanation for the apparent license with which the young behave online. 42 percent of young Americans answered all of our five online privacy questions incorrectly. 88 percent answered only two or fewer correctly. The problem is even more pronounced when presented with offline privacy issues – post hoc analysis showed that young Americans were more likely to answer no questions correctly than any other age group. |

|

Americans Reject Tailored Advertising and Three Activities that Enable ItJoseph Turow, Jennifer King, Chris Jay Hoofnagle, Amy Bleakley and Michael HennessyCite as: Joseph Turow et al., Americans Reject Tailored Advertising and Three Activities that Enable It (Sept. 29, 2009), available at http://ssrn.com/paper=1478214. This nationally representative telephone (wire-line and cell phone) survey explores Americans’ opinions about behavioral targeting by marketers, a controversial issue currently before government policymakers. Behavioral targeting involves two types of activities: following users’ actions and then tailoring advertisements for the users based on those actions. While privacy advocates have lambasted behavioral targeting for tracking and labeling people in ways they do not know or understand, marketers have defended the practice by insisting it gives Americans what they want: advertisements and other forms of content that are as relevant to their lives as possible. |

|

What Californians Understand about Privacy OnlineChris Jay Hoofnagle & Jennifer KingCite as: Chris Jay Hoofnagle & Jennifer King, What Californians Understand about Privacy Online, Sept. 3, 2008, available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1262130. The volume of online commerce grows every year, in absence of a federal law setting baseline protections for the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information. Instead, information collected by websites are governed by individual privacy policies. In order to gauge Californians’ understanding of privacy policies and default rules in the online environment, we commissioned a representative survey of adults in the State (N=991). The telephonic survey of Spanish and English A gulf exists between California consumers’ understanding of online rules and common business practices. For instance, Californians who shop online believe that privacy policies prohibit third-party information sharing. A majority of Californians believes that privacy policies create the right to require a website to delete personal information upon request, a general right to sue for damages, a right to be informed of security breaches, a right to assistance if identity theft occurs, and a right to access and correct These findings show that California consumers overvalue the mere fact that a website has a privacy policy, and assume that websites carrying the label have strong, default rules to protect personal data. In a way, consumers interpret privacy policy as a quality seal that denotes adherence to some set of standards. Website operators have little incentive to correct this misperception, thus limiting the ability of the market to produce outcomes consistent with consumers’ expectations. Drawing upon earlier work, we conclude that because the term privacy policy has taken on a specific meaning in the minds of consumers, its use should be limited to contexts where businesses provide a set of protections that meet consumers’ expectations. |

|

What Californians Understand about Privacy OfflineChris Jay Hoofnagle & Jennifer KingChris Jay Hoofnagle & Jennifer King, What Californians Understand About Privacy Offline, May 15, 2008, available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1133075. Many online privacy problems are rooted in the offline world, where businesses are free to sell consumers’ personal information unless they voluntarily agree not to or where a specific law prohibits the practice. In order to gauge Californians’ understanding of business practices with respect to the selling of customer data, we asked a representative sample of Californians about the default rules for protecting personal information in nine contexts. In six of those contexts (pizza delivery, donations to charities, product warranties, product rebates, phone numbers collected at the register, and catalog sales), a majority either didn’t know or falsely believed that opt-in rules protected their personal information from being sold to others. In one context – grocery store club cards – a majority did not know or thought information could be sold when California law prohibited the sale. Only in two contexts – newspaper and magazine subscriptions and sweepstakes competitions – did our sample of Californians understand that personal information collected by a company could be sold to others. Respondents who shopped online were less likely to say that they didn’t know the answer to the nine questions asked than those who never shopped online. In about half of the cases, those who shopped online answered correctly more often than those who do not shop online. Professor Alan Westin has pioneered a popular “segmentation” to describe Americans as fitting into one of three subgroups concerning privacy: privacy “fundamentalists” (high concern for privacy), “pragmatists” (mid-level concern), and the “unconcerned” (low or no privacy concern). When compared with these segments, Californians are more likely to be privacy pragmatists or fundamentalists, and less likely to be unconcerned about privacy. Fundamentalists were much more likely to be correct in their views of privacy rules. In light of this finding, we question Westin’s conclusion that privacy pragmatists are well served by self-regulatory and opt-out approaches, as we found this subgroup of consumers is likely to misunderstand default rules in the marketplace. |