By Gwyneth K. Shaw

The deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and countless other Black people at the hands of law enforcement sparked protests in cities across the country last year and pushed the movement for police reform to new prominence.

But how to turn the ideas into new policies, particularly given the strength of police unions, which continue to wield an outsized influence over law enforcement agencies and the politicians who oversee them?

A recent Berkeley Law symposium brought many eminent voices on all sides of the debate together for a lengthy discussion of how to make real change. Presented by the brand-new Center for Law and Work, “Reforming Policing Through Changing Labor Relations” featured experts from the legal, academic, and policy realms talking about the best way forward.

Berkeley Law Dean Erwin Chemerinsky, who opened the symposium, said the topic couldn’t be more important or timely. Having served on the task force that investigated the Ramparts scandal in the Los Angeles Police Department in the 1990s, he said the police themselves — and the unions that represent them — are critical to reform efforts.

“My hope is that the national protests that occurred last spring focused attention on the problems of policing in a new way and provide a basis for reform greater than we have ever seen,” Chemerinsky said. “And it’s crucial that we take advantage of that intention and that energy to bring about meaningful police reform.”

Among the experts who spoke were Christy Lopez, a professor at Georgetown Law and co-director of its Program on Innovative Policing; Will Aitchison, a veteran lawyer who represents police and fire unions; Paul Henderson, director of the San Francisco Department of Police Accountability; California State Senator Nancy Skinner, a Democrat who represents the Berkeley area; and arbitrator and attorney Jeanne Charles.

“I’m not against police unions, but I do think the current system is really broken,” Lopez said.

New ideas emerge

She and others talked at length about various paths to changes, noting some of the ideas advanced in a recent California Law Review Online article by several symposium moderators, including Berkeley Law Professor and CLAW Co-Director Catherine Fisk ’86 and retired U.S. District Judge Thelton Henderson ’62.

“We’re hoping very much that the discussion will contribute to law and policy reforms of policing going forward,” Fisk said.

Among those ideas: greater transparency of contract negotiations, disciplinary actions, and the arbitration process to settle disputes. Another is to make use of force policies, which govern how officers conduct themselves, a negotiated part of the labor contract between police and cities.

Aitchison said he couldn’t think of a police department where the use of force was incorporated into a contact, and that a blanket policy might prove too restrictive. But he welcomed some of the other ideas.

“I would love to have arbitration hearings in the public,” he said. “I would love for the public to be able to understand what led to some of these high-profile arbitrations that we’ve seen.”

It’s also not just about the use of force, Lopez noted.

“We just need to get serious about not allowing people with white supremacist beliefs to hold a badge or a gun,” she said. “That’s not about your First Amendment right.”

A long but hopeful road

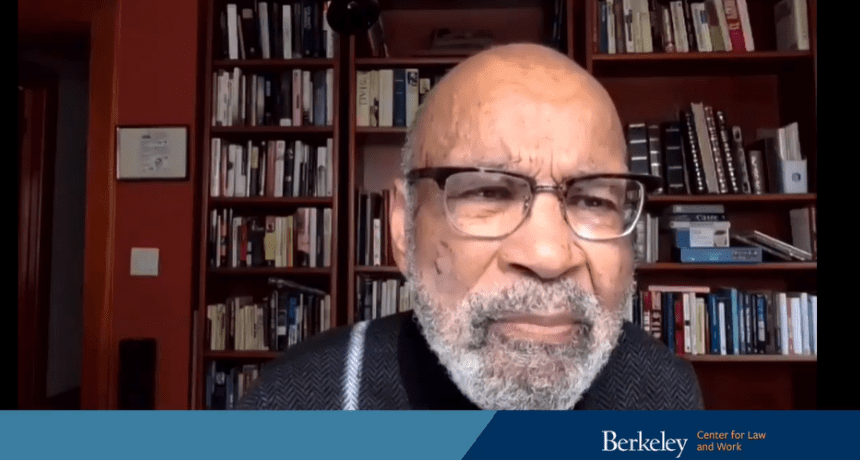

Henderson, for whom Berkeley Law’s center for social justice is named, gave the keynote address. It mostly focused on his involvement as a judge overseeing a lengthy lawsuit against the Oakland Police Department over conduct by a group of officers known as the “Riders.” The city settled the suit in 2003, but enforcement of the settlement stretched beyond Henderson’s 2017 retirement from the bench.

He recalled one police chief in particular who told Henderson he was eager to resolve the case, only to tell union leaders he was just playing along. Given the political clout police unions now enjoy, “it will take significant changes to make a difference given the deeply embedded, deeply divided society that we live in,” Henderson said.

Until that process moves forward, he said he has no doubt many law enforcement officers and agencies will continue paying lip service to compliance without actually living up to court-imposed conditions.

“All of us here today are faced with a Herculean task — one which, at bottom, is structural and systemic. And we all know that changing the failings and shortcomings that I’ve been discussing will not come about with a single stroke of a pen,” Henderson said. “But we do have the ability to begin the process of making changes to our labor relations laws that will contribute to the transformation of policing.”

The work can begin, he said, with a close look at why there seems to be so little accountability in so many cases involving police brutality, in particular the disciplinary protections police have successfully negotiated for themselves.

“It will take time,” he said. “But now is the time to begin the process.”