By Andrew Cohen

By approving Proposition 209, California voters barred state institutions from considering race, sex, or ethnicity within public education, contracting, and employment. Two decades later, a revealing Berkeley Law symposium explored its massive impact on legal education, minority students, and campus racial dynamics.

The school’s first class after Prop. 209 had just one African American—panelist Eric Brooks ’00—who was actually admitted before the vote and had deferred. Brooks shared some painful memories of navigating life in an unexpected spotlight.

“I had to give a press conference on my first day because the media basically demanded it,” recalled Brooks, now senior counsel for the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

“Classroom divisions caused by this hot-button issue created a very tense experience that first year. Being the only African American in the class was like a kick in the gut.”

Brooks felt pressured “to represent the whole African-American community” and to make sure groups like Law Students of African Descent and the Berkeley Journal of African-American Law & Policy survived. “There were a couple years where all I did was try to keep the lights on,” he said.

Symposium panel moderator Tirien Steinbach ’99, executive director of the East Bay Community Law Center, was part of the last class admitted before Prop. 209. She noted that Berkeley Law’s current first-year class has 28 African Americans—the most since Prop. 209—and the importance of “showing diversity within the black community.”

Steinbach added, however, that “diversity is like having a vase of beautifully cut flowers that eventually wither and die. True equity and inclusion require a huge amount of effort and lots of hands to water and weed, water and weed, and keep at it forever.”

Isolation impact

Panelist Quyen ’03 Ta, a partner at Boies Schiller Flexner and the winner of this year’s Berkeley Young Alumni Award, was 2½ when her family migrated to the U.S. from Vietnam. Valedictorian of her high school class and a summa cum laude graduate from UCLA, law school still “felt like being back in my remedial elementary school class learning English,” she said. “When you don’t have role models or critical mass, it’s difficult.”

More than 80 percent of California’s lawyers are white in a state that is no longer majority white. Ta described empirical and anecdotal evidence of how diverse legal teams achieve greater success, and lamented how Prop. 209 has diluted such opportunities.

Berkeley Law student Cheyenne Overall ’19, who experienced Prop. 209’s impact as “the only black person in my dorms and most of my classes” as a UC Berkeley undergrad, hailed Berkeley Law’s decision “to ensure that no black student would be alone in their first-year section.”

On an earlier faculty panel, Seattle University law professor Robert Chang described the complicated Asian-American space within the affirmative action debate. Discussing the 2016 case Fisher v. University of Texas, he noted that four Asian-American groups submitted amicus briefs—two for the plaintiff and two against.

“Asian Americans sometimes get aligned with whites as a ‘model minority’ versus being aligned with African Americans and Latinos,” Chang said.

Realities of race

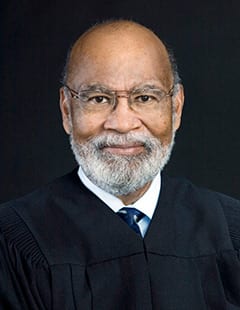

The day after voters passed Prop. 209, a federal lawsuit was filed declaring the ballot measure unconstitutional. The case got assigned to Judge Thelton Henderson ’62, one of just two African-Americans in his graduating class and the first African-American attorney in the U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division.

Now a visiting professor at Berkeley Law, he granted a temporary restraining order and later an injunction barring enforcement of Prop. 209 until a trial. “I was aware, as the song says, that this could be the start of something big,” said Henderson, who reviewed the case’s procedural history during his opening keynote address. “But I had no idea about the degree of the controversy awaiting me.”

Henderson’s ruling sparked a strong response from Prop. 209 advocates, some of whom called for his resignation. He received hate mail and death threats, prompting the FBI to take over reviewing his mail and U.S. Marshals to monitor his home in two unmarked cars from sundown until morning.

Even during routine court matters, “suddenly there was the appearance in my courtroom of people who often sat in the front row and had facial expressions of disgust and hatred,” Henderson said. “Menacing figures who were there to just let me know they were watching me.”

In April 1997, the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the constitutionality of Prop. 209.

“It was very disappointing to see this grind to a halt without the benefit of a full hearing on the merits,” Henderson said. “The year after Prop. 209, Berkeley Law’s entering class had one African-American student (Brooks). My graduating class in 1962 was the first in the law school’s history to graduate two African Americans. From my perspective, Prop. 209 had set us back to a time before 1962.”