By Andrew Cohen

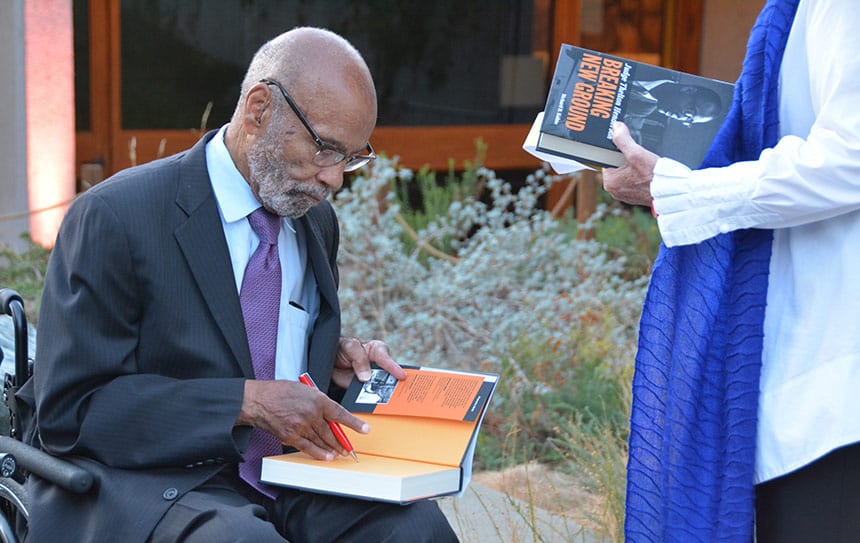

For many in the Berkeley Law community, Judge Thelton Henderson ’62 is an almost mythical figure. The first African-American lawyer at the U.S. Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division in the early 1960’s, he routinely faced dangerous, racially charged situations while confronting unjust voting rights practices in the Deep South. A trusted advisor of Martin Luther King, Jr., he opened a legal aid office, helped diversify law schools, and spent 37 years as a federal judge.

For years, Berkeley Law students eager to aid the disadvantaged have worked at the Thelton E. Henderson Center for Social Justice. Now, they will have a chance to gain wisdom, insights, and career advice from the judge himself, who recently returned to the school as a distinguished visitor for this academic year.

Some of those students will also be eligible for a new endowed fellowship in his name, announced during a spirited retirement dinner for Henderson on September 28 at the Oakland Museum of California. The fellowship, made possible by two dozen sponsors, will provide summer employment funding each year for an exceptional Berkeley Law student to engage in otherwise unpaid racial justice work.

“This fellowship keeps faith with all the Henderson Center has stood for since its inception,” said Executive Director Savala Trepczynski ’11. “It serves the greater community and indeed the nation as we grapple with racial equity, and it honors Judge Henderson’s legacy as a champion for racial justice.”

As for returning to Berkeley Law, Henderson freely admits it was nowhere on his radar as he approached his retirement from the bench last month.

“It really came out of the blue,” Henderson said of the invitation by Dean Erwin Chemerinsky, Professor David Oppenheimer, and Trepczynski asking if he would consider a distinguished visitor position. “The more I thought about it, the more it felt like a great transition. It fits perfectly with what I’m passionate about: working with students and helping young people find their path.”

Holding court

Henderson will hold office hours with students, co-teach parts of classes, act as an advisor on the school’s various social justice projects, and assist in writing amicus briefs. Professor Emeritus William Fletcher has already invited him to co-teach part of his Federal Courts course, and Oppenheimer has extended the same offer for his Comparative Equality and Anti-Discrimination Law course.

“Thelton Henderson is an institution and a hero here at Berkeley,” said Oppenheimer, a Henderson Center co-faculty director. “We’re thrilled that he wanted to enrich our community in this way.”

Trepczynski noted that law students and young lawyers typically only have regular, instructive contact with a judge during an externship or clerkship.

“Now, every one of our students can learn from, and work alongside, an extraordinary jurist who also happens to be an affable and generous man,” she said. “Judge Henderson’s presence creates a beautifully democratized opportunity for unique learning and mentorship. We couldn’t be happier about his choice to join this community again.”

Henderson anticipates a natural transition after having engaged in similar activities with more than 70 of his law clerks over the years. He has spent “tons of hours” guiding them and discussing the many paths to rewarding public service work.

“Many law students want to be public defenders, which is wonderful, but some don’t realize how much the deck is stacked against them in that position,” he explained. “I tell them, ‘If you really want to serve the public and do good, wouldn’t it be great to be a prosecutor with your values?’ Other students feel guilty about joining a big firm, but need to do that to pay off their student debt. That’s perfectly fine; many firms make huge pro bono commitments and advance social justice. There are multiple platforms for serving those in need.”

An enduring legacy

On the federal bench, Henderson developed a powerful reputation for his judicial acuity and sensitivity.

In 1986, he wrote the opinion in a case that first outlawed sexual harassment in California. In 1995, his lengthy ruling on dire conditions at Pelican Bay State Prison led to vital restrictions on the state’s use of solitary confinement. In 2006, he ruled that the state was violating constitutional standards with deficient prison medical treatment—resulting in needless inmate deaths—and appointed a receiver to manage the prison health care system.

“I remember colleagues on the bench talking about these huge cases that cost millions of dollars. I worked hard on those cases, but didn’t have much passion for them,” Henderson said. “My passion focused on cases in which individuals were getting short-changed or were underdogs against a system that seemed stacked against them.”

Looking back on his own law student days, Henderson recalls how various people helped him navigate a new culture and shape his career aspirations. Professor Adrian Kragen, a renowned tax expert, is one that stands out.

“Mentorship is important to me because it was important for me,” Henderson said. “I love telling students that Thelton Henderson, who they think of Mr. Civil Rights, first wanted to be a tax lawyer like Adrian.”

As an assistant dean at Stanford Law School from 1969 to 1977, Henderson established the school’s minority recruiting program and helped establish its clinical program. He relishes returning to the law school world, particularly at his alma mater.

“I really enjoy interacting with law students,” he said. “I tell them, ‘Don’t think I was born into a black robe. There were lots of twists and turns before that happened.’ I like to remind them of the many paths to a gratifying career, and help them find what suits them best.”