By Andrew Cohen

Chancellor’s Professor Emeritus Harry Scheiber recalled a memorable moment from his freshman year at Columbia, when an instructor reviewed his first architecture project. “He told me, ‘You have no talent for this field,’ Scheiber said with a laugh. “So I became a historian.”

Architecture’s loss was history’s gain. With his latest book, Constitutional Governance and Judicial Power: The History of the California Supreme Court, Scheiber charts a compelling journey from humble beginnings to one of the nation’s most respected state courts. He also explores its hefty impact on California’s cultural, socio-economic and political landscape.

“This is truly a major opus,” Interim Dean Melissa Murray said at a January 18 event celebrating the book’s release. “It couldn’t be more timely as we’re thinking deeply about the role state courts play in this country.”

The prolific Scheiber has written, edited or contributed to dozens of books at the intersection of law and history. Faculty director of Berkeley Law’s Institute for Legal Research, he held the Stefan Riesenfeld Chair and served as director of the school’s Sho Sato Program in Japanese and U.S. Law.

In this book, he edited a series of chapters by fellow scholars, including Lecturer in Residence Charles McClain, a longtime administrator and instructor in Berkeley Law’s Jurisprudence and Social Policy (JSP) Program; and JSP graduate Lucy Salyer ’89, an associate professor at the University of New Hampshire.

“It was a privilege to work with these authors,” said Scheiber, who praised them for helping him amplify “the importance of state-level history” while documenting the court’s first 165 years.

The final product is arguably the most complete, authoritative study of any state supreme court. University of Southern California Professor Kevin Starr, a leading scholar of California history, called Scheiber’s book “masterful … skillfully integrating jurisprudential scholarship with social, economic, cultural and political issues.”

Growing pains

McClain’s two chapters included one on the court’s first 30 years—when it made some disturbing rulings. They included People v. Hall, which held that Chinese-Americans could not testify against whites in criminal cases.

In another troubling verdict, a man who had brought his slave to California was allowed to recover him after the slave escaped—and to bring him back to his home state—even though slavery was illegal in California.

McClain was also struck by “how much the court relied on Mexican and Spanish law in its early decisions.”

But California soon began burnishing its reputation as a leading progressive state, said Salyer, who wrote about the court from 1910 to 1940 and its role in that process. “Many programs we know well today were seen as revolutionary back then,” she said, noting major developments in women’s rights, criminal justice and the regulation of public utilities. “The court also struck down a law that imposed taxes on non-citizens … but was still inhospitable on civil rights and free speech.”

McClain’s chapter on the court under Chief Justice Phil Gibson from 1940-1964 chronicles how it “rose to become the premier state appellate court in the country.” Berkeley Law graduate Roger Traynor ’27, the court’s first justice with an academic background, propelled what McClain called “an expansive view of the law’s potential to affect significant social change.”

Scheiber wrote about the court’s jurisprudence from 1964 to 1987, when it tackled myriad crises. “This was a period of enormous change,” he said. “The LA riots, school busing, gay rights, farm strikes, affirmative action in the UC system—all truly divisive issues. There were some amazing intellects on the court during this time who held a deeply-rooted sense of the need to respect diversity … and to protect consumers in the corporate world.”

The court featured a strong Berkeley Law connection during the 1980s with Associate Justice Matthew Tobriner ’32, a leading figure in state constitutional law; Associate Justice Frank Newman ’41, former professor and dean; and Chief Justice Rose Bird ’65.

Both author and mentor

Scheiber’s collaborative approach reflects his affinity for cross-disciplinary partnerships and eagerness to work with people at all levels of legal scholarship. His impact on colleagues was evident throughout the event celebrating his book, which Salyer called “a testament to Harry’s vision and dedication. He’s such a persistent and passionate advocate of the need for this kind of history.”

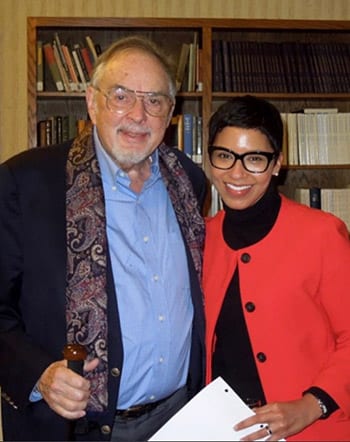

Last year, Jordan Diamond ’08 and Professor Holly Doremus ’91 took the reins of the Law of the Sea Institute from Scheiber, its longtime director. Diamond, also the executive director of the school’s Center for Law, Energy & the Environment, credits Scheiber for paving her career path.

“When I was a law student here, becoming Harry’s research assistant was one of those life-changing moments,” she said. “He’s had an enormous influence on me as an advisor, mentor and, most importantly, as a friend.”

Murray recalled Scheiber taking her to lunch soon after she joined Berkeley Law’s faculty in 2006, and how he “so deeply cared about his role as a mentor.” She said his new book, which incorporates the work of “many young colleagues,” highlights an inclusive approach that helped produce “another masterpiece.”