By Andrew Cohen

In Norway or the United States, during breezy times or mid-pandemic, visiting scholar Nertila Kuraj never wavers when describing her home away from home.

“My longstanding interaction with Berkeley Law is by far one of the most fruitful, thrilling, and inspiring experiences of my academic career,” she says. “It’s an incredible crossroads of people, ideas, and ideals, where world-class academic research meets equally important social engagement to some of the most pressing challenges of our time … a place where magic happens.”

A prime example: Kuraj and Professor Daniel Farber receiving a 2020 Peder Sather Grant for their collaborative research project. Titled Towards a Global Summit on Gene Editing for Environmental Purposes? An interdisciplinary debate on risk, uncertainty and precaution in the new genetic era, their study assesses regulatory needs for the fast-developing field of gene editing for environmental purposes.

While human gene editing has sparked widespread debate regarding its moral, ethical, and social implications, such debate is lacking within its growing environmental applications. Kuraj and Farber want to change that by connecting prominent scientists and lawyers working on the issue, fostering an exchange of potential solutions to the legal bottlenecks and uncertainties now deterring a thorough assessment of the risks and benefits involved.

A postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Oslo, Kuraj says Farber’s “erudite knowledge and excellent mentorship have been invaluable.” She hopes to cap the project with a white paper and a conference hosted by Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy & the Environment, where Farber is the faculty director.

“The topic of gene editing seemed perfect as a joint project, given that Berkeley is a world leader in the field and that we’re already beginning to see potential environmental implications,” Farber says. “This is an emerging topic, so we wanted to bring together leading thinkers in all the relevant fields. Nertila deserves full credit for taking this project from a general concept to fruition.”

Prolific partnerships

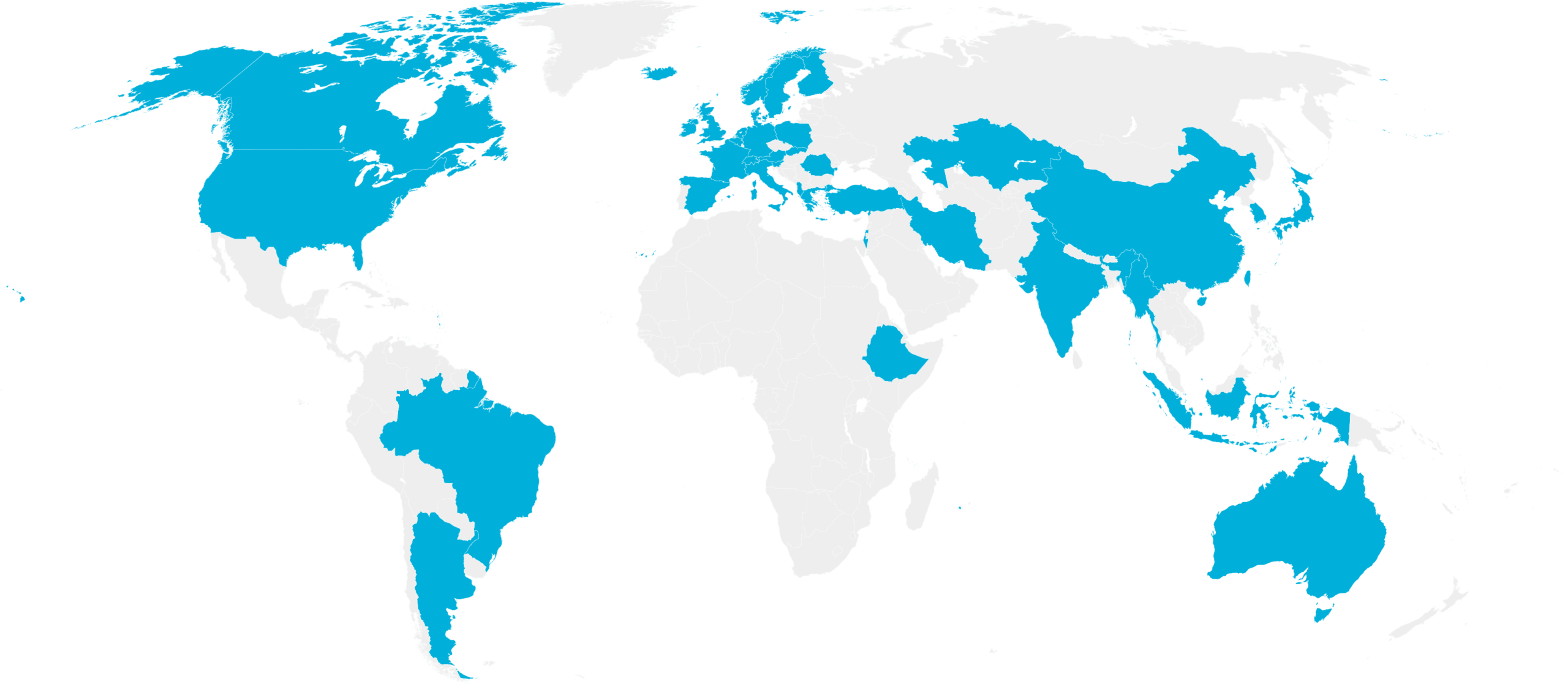

Scholars and researchers from around the world flock to Berkeley Law’s Visiting Scholars Program to engage in independent and collaborative legal research. Promoting a robust exchange of ideas, education, and culture, the program offers a transformative immersion in the study of law through partnerships with the school’s world-class faculty members, centers, and programs.

Kuraj was a visiting researcher at Berkeley Law in 2014, studying the legal dimensions of nanotechnology, and last year published a book on the subject titled REACH and the Environmental Regulation of Nanotechnology. She returned in 2018 for two years thanks to a grant from the Research Council of Norway, and began exploring areas of mutual interest with Farber.

Their current project concerns the regulation of synthetic biology (synbio), an intersectional convergent technology combining biology and engineering. It strives to engineer new biological systems that do not exist in nature, and to redesign existing systems from scratch.

Examples include the creation of bacteria that can synthetize a precursor of the anti-malarial drug artemisinin and the “birth” of Synthia. The latter is a new bacterium created by synthesizing an entire genome through a computer-based record and transforming it into the first truly synthetic organism.

“UC Berkeley was where significant breakthroughs in synbio advancements were taking place at the time I wrote the project proposal that enabled me to come back here,” Kuraj says. “It’s imperative to address the most pressing risks and uncertainties involved in gene editing for environmental purposes, which cannot be underestimated.”

The Sather project builds on the synbio one and addresses CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats), a Berkeley invention that MIT Technology Review called “the biggest biotech discovery of the century.” UC Berkeley Professor Jennifer Doudna recently won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry after her lab discovered a new way to deliver CRISPR-based gene editing into plant cells. Its many applications include using it to alter human genes to eliminate diseases and to improve plant drought resistance.

“These are crucial pursuits in a resource-drained and over-populated planet in the grip of a climate change emergency,” Kuraj says. “Gene drives, a prime example where synthetic biology and CRISPR technology can be combined, are deemed important where climate change could contribute to the spread of malaria-carrying mosquitoes and other invasive species of pests and weeds worldwide. Berkeley scientists are among the pioneers of testing ways of using CRISPR to edit the genome of disease-carrying mosquitoes with the aim of suppressing them on a continental scale.”

The technology carries a number of risks, however, such as potential biodiversity disruption, making it imperative to address such risks early as gene drives also carry the potential of irreversibility affecting the global commons.

Early incentive

Kuraj grew up in Elbasan, Albania, a city heavily polluted from a metallurgical complex operating near inhabited areas. She laments that little has been done there to minimize environmental degradation, and commonly hears about genetic anomalies affecting nearby livestock and high tumor rates among the area’s population.

“This tragic situation and the damage that an unregulated and totally unchecked industry was causing to an otherwise beautiful city, and the deep frustration and sense of injustice I felt about the harm being done to nature and to people for the sake of a profit, awoke in me the passion for environmental law and justice at a very early age,” Kuraj says.

At 18, she received a full scholarship to study law in Italy and earned a bachelor’s degree and an LL.M. in EU and International Law. After almost 11 years in Italy, she accepted a fully paid Ph.D. position at the University of Oslo.

“Studying and working in different countries has contributed to the interdisciplinary nature of my research,” she says. “It has also boosted my understanding of different legal cultures and legal regimes — and the way such regimes approach the main concepts that form the object of my research’s inquiry.”

Although the COVID-19 pandemic has forced the cancellation of in-person academic activities and workshops, Kuraj’s environmental passion and project commitment remains unbowed — and emblematic of Berkeley Law’s visiting scholars.

“They bring expertise from legal systems all over the world to Berkeley,” Farber says. “I’ve developed connections with visiting scholars that lasted far beyond the time they were on campus. As a result of these visits, I’ve had long-term collaborations with scholars from countries such as Brazil, Italy, Korea, and Japan. Those wouldn’t have happened otherwise.”