Each day in California, young people are incarcerated for technical violations of the onerous rules of electronic monitoring (GPS)—even though they haven’t committed any crime.

Students are sent away from their schools because principals don’t want to admit students wearing GPS monitoring devices. Young people miss job interviews, family gatherings, team practices, and after-school programs for fear of being caught stepping outside boundaries strictly drawn by their probation officers. And each day, more of them are shackled with GPS tracking devices because of decisions made by adults who see such monitoring as a better alternative to incarcerating children.

Students and advocates at the East Bay Community Law Center (EBCLC) are all too familiar with the cascade of consequences resulting from the use of GPS monitoring in juvenile court. Those consequences include sharp racial disparities, unsuitable conditions for children with disabilities, and cycles of recidivism spurred by technical violations of GPS rules.

“Ultimately, we’d like to eradicate GPS monitoring of youth, but we’re also interested in the pragmatic next step to reform it,” says attorney Cancion Sotorosen, clinical supervisor at EBCLC’s Youth Defender Clinic. “There needs to be greater recognition that GPS is not a panacea to keep kids out of detention, that it’s caused problems no one anticipated, and that now we have to grapple with those.”

Over the past few years, the clinic has represented GPS-monitored youth in the Alameda County juvenile court system, produced scholarly research on the far-reaching implications of using electronic monitoring with youth on probation, and advocated for policy changes at the county level. Now, the clinic is initiating next steps to build a nationwide movement to reform the use of this widespread surveillance mechanism.

First gathering of its kind

The first step took place on October 11, when Berkeley Law students and clinicians brought together a group of more than 50 activists, researchers, public defenders, journalists, and impacted young people from four different states. EBCLC and the school’s Samuelson Law, Technology & Public Policy Clinic, research and advocacy leaders on this issue, organized the event.

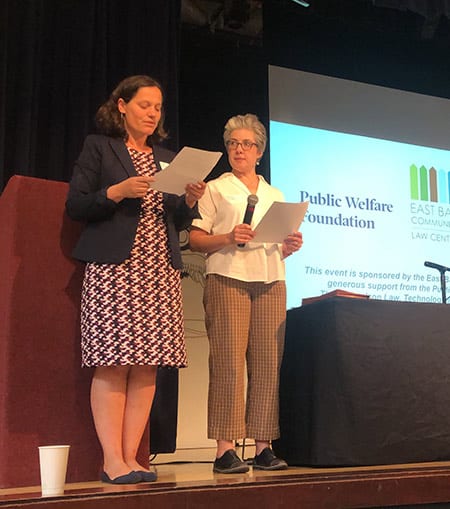

Led by Sotorosen and George Washington University Law Professor Kate Weisburd ‘05—the founder of EBCLC’s Youth Defender Clinic—the all-day strategic convening on “The Future of GPS Monitoring in Juvenile Court” took place at the Oakland Asian Cultural Center.

“This is the first gathering of its kind,” Weisburd said. “It’s the first time people have come together to talk about electronic monitoring in the context of the juvenile legal system.”

Students played a key role in organizing the event, which involved two panels, a breakout discussion, and whole-group strategy sessions to change minds—and laws—around GPS monitoring of youth.

The first panel, moderated by EBCLC Clinical Supervising Attorney Oscar Lopez, began with moving testimony from a young woman who was tracked with a GPS monitor off and on during her time on probation. Panelist David Muhammad, director of the National Institute for Criminal Justice Reform, spoke to the superior efficacy of mentorship programs in supporting system-involved youth.

“It’s not just about ‘Are you where you’re supposed to be?’, but ‘What support can we provide you?’” said Muhammad, who has led criminal justice agencies in Washington, D.C. and Alameda County. “That’s far more effective than some electronic strap around your ankle that is, for the court, a false sense of security. Many people end up doing something with an ankle monitor strapped to them that we would prefer they not do.”

Research revelations

Weisburd moderated the second panel, “GPS In Juvenile Court: What We Don’t Know, But Should.” Following more powerful testimony from an impacted young person, panelists discussed various data holes that need filling.

Samuelson Clinic Director Catherine Crump spoke to her clinic’s new research on the surveillance, privacy, and civil rights implications of GPS monitoring. “These devices collect massive quantities of data, and we’ve had very little information about how long the probation departments keep the data and who they share it with,” she said.

In investigating these questions, Crump found that many California probation departments share most or all GPS data with law enforcement agencies, subjecting people to a continuous cycle of searching and monitoring. The Samuelson Clinic’s report on this research will soon be released.

At the close of the convening, participants discussed the best ways to leverage the day’s momentum to impact real change in the lives of system-impacted young people. For the Youth Defender Clinic, this could mean developing a “toolkit” for local advocates trying to curtail and modify GPS usage at the county level, as well as building an online resource bank to host stories, statistics, and strategies in the nationwide movement to reform GPS.

Although she anticipates a long fight ahead, Sotorosen expressed a positive outlook when it comes to changing minds—and laws—around the electronic monitoring of youth.

“When it comes to juvenile justice, we’ve seen so many positive trends in the last 15 years,” she reflected. “The number of children being sent to group homes and being locked up has gone way down, and in Alameda County the number of kids on GPS has gone down, too. If we can effectively harness the energy in this room, we’re well-situated to scale that success up to the statewide and national level.”