By Andrew Cohen

In March, as Berkeley Law students began adjusting to online classes, social distancing, and other life changes to avert COVID-19, those who work with the Prisoner Advocacy Network knew their clients lacked the same ability to protect themselves.

A broad organization of attorneys, activists, legal workers, and law students, PAN promptly sprung into action. Its Berkeley Law chapter played a vital role in crafting a new habeas self-help litigation guide to help incarcerated people in California—one of several COVID-19 resources PAN has created and made available.

The guide provides information for how state prisoners can seek release through a petition for writ of habeas corpus related to COVID-19, factual and legal analysis for educational purposes, and sample language for potential filings.

“We all recognized the urgency of providing resources to help incarcerated people avoid COVID-19,” says Ben Holston ’21, co-director of Berkeley Law’s PAN chapter. “It has been inspiring to see so many students doing what they can to help.”

Holston, fellow co-director Melissa Barbee ’21, and seven other Berkeley Law students—Tiara Brown ’22, Savannah Wheeler ’21, Luke Sironski-White ’22, Jennifer Chung ’22, Cameron McKenzie ’22, Spence Jones ’22, and Ty Clarke ’21—collaborated on the guide with students from Harvard, Penn, and NYU. Wheeler and Clarke co-directed the Berkeley Law chapter last year, and McKenzie and Jones will lead it next year.

Supervising attorneys Caitlin Henry and Taeva Shefler coordinated the guide’s development, advising on practical law and assigning research sections to each student.

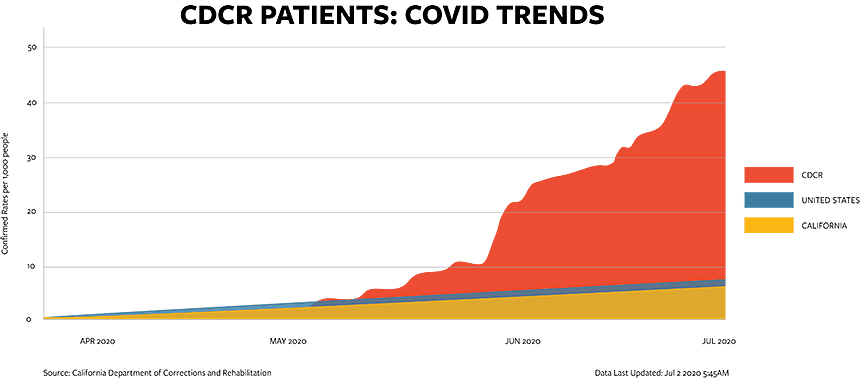

“COVID-19 remains a deadly and uncontrolled threat inside California prisons, with more than 3,000 incarcerated people having tested positive,” Barbee says. “California’s Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation still hasn’t implemented mass testing of its own staff, which is the main vector for spreading the virus in prisons.”

A troubling track record

California prisoners are often housed in close quarters with dozens of other people, greatly increasing their likelihood of contracting COVID-19. The U.S. Supreme Court ordered California to dramatically reduce its prison population in 2011, and ongoing lawsuits claim that constitutionally adequate medical care has not been provided.

Such substandard care increases the number of prisoners who develop pre-existing medical conditions—which make serious complications and death due to COVID-19 more likely.

Many prisoners are also elderly and at heightened risk because of the state’s history of imposing lengthy sentences.

“Our hope is that this guide leads to the release of as many people as possible, particularly those at increased risk of complications from the virus,” Holston says. “PAN is sharing the guide with jailhouse lawyers, families of incarcerated people, and other attorneys who can help incarcerated people file state habeas petitions to seek release.”

The group’s original draft approached 200 pages and involved extensive research on subjects many of them were unfamiliar with before the project. Beyond the state habeas guide, Berkeley Law students also contributed to a guide to administrative appeals inside California prisons and an overview of additional routes to release that incarcerated people can pursue.

The state habeas guide was released on May 25—the same day George Floyd was killed by a Minneapolis police officer, setting off a seismic wave of protests and advocacy for major racial justice reforms. According to a recent report, California’s incarceration rate is nearly seven times higher for Black people (3,036 per 100,000) than White people (453 per 100,000).

“As the recent protests have highlighted, this is not an accident,” Barbee says. Citing the “woefully inadequate medical care available to incarcerated people,” she says “a temporary sentence should not turn into a death sentence just because a prison fails to take care of its incarcerated population.”

The right niche

Racial and power inequities were core reasons why Barbee, an Air Force veteran with 12 years of military service, wanted to join PAN.

“I’m familiar with how readily people in positions of power abuse their power when there’s no one holding them accountable,” she says. “Prison is a place where the power balance is so hopelessly tipped … When I came to Berkeley Law, I looked for a place I could direct my energy toward challenging that imbalance.”

The students’ work is already gaining traction. Excerpts from the guides were published in the May issue of Prison Focus (2,500-plus circulation), and an April 11 webinar put together by PAN leadership and moderated by Brown has been viewed more than 4,200 times.

On June 11, a federal court ordered mass testing of California prison staff, and to immediately suspend transfers of incarcerated people between prisons without proper protections, to mitigate the risk of spreading the virus. The order followed a decision by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation to transfer 121 incarcerated people to San Quentin—despite failing to test many of them for more than two weeks—resulting in an outbreak that has since infected more than 1,100 San Quentin prisoners.

“Typically, Berkeley Law students working with PAN advocate for individual incarcerated people, which I’ve found fulfilling because it’s a chance to establish a relationship with someone inside,” Holston says. “That being said, the work we have done on this state habeas guide has easily been the most rewarding aspect of my time with PAN.”