By Andrew Cohen

Recounting her summer with the International Refugee Assistance Project, Forogh Bashizada ’23 delved into vexing challenges and nuanced strategies used to address them. But during a recent Human Rights Center fellowship presentation, she captured the essence of her memorable experience with nine simple words:

“In my clients I saw myself and my family.”

As a young child, Bashizada fled Afghanistan with her family and immigrated as refugees to Washington State. Years later, she said, “I stood on the other side as a legal advocate helping individuals who were enduring what my own family went through.”

Bashizada helped her organization serve persecuted migrants by mobilizing direct legal aid, litigation, and systemic advocacy. She helped vulnerable clients navigate pathways to safety, assisted in bringing legal challenges to refugee rights violations, strived to overcome resettlement process barriers, and worked to develop an enforceable system of legal and procedural rights for refugees and displaced persons.

Citing bureaucratic red tape as a key theme of her summer experience, Bashizada called it the common denominator in impeding refugee pathways. She was struck by how “incredibly difficult and lengthy the refugee process was and is” and how “even the smallest thing can cause a rejection.”

But Bashizada added that migrant resilience was an equally powerful theme, describing how she was constantly awed by the strength and bravery shown by clients she worked with.

“Society has relegated refugees to the fringes, on the margins, in the shadows, where they are just numbers and statistics and collateral damage,” she said. “That’s why it is so important that refugees not be nameless and forgotten but rather seen as human beings. They are teachers, doctors, musicians, innovators, artists. They are our neighbors, our classmates, and in this case, a law student presenting in front of you today.”

Flourishing formula

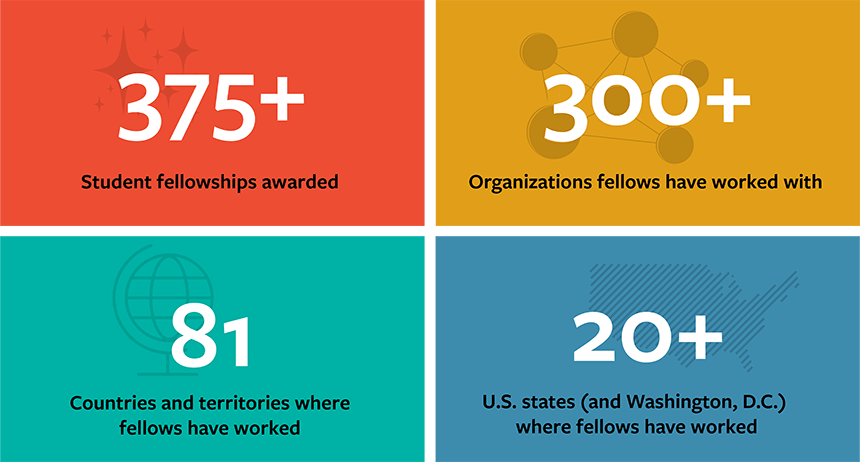

Launched in 1994 and funded largely through the generosity of Thomas White and Clinical Professor of Law Emerita Carolyn Patty Blum, the fellowship program has supported more than 375 UC students working in over 80 countries and territories worldwide.

Bashizada and fellow Berkeley Law students Sara Osman ’22, Naomi Spoelman ’22, and Helena von Nagy ’22 joined this year’s cohort of 21 Human Rights Center summer fellows. All four of them are also students in the school’s International Human Rights Law Clinic, and Spoelman received the annual fellowship designated for a student from the clinic.

Each year, the center showcases their work through individual student fellow presentations. This year’s presentations, which can be seen here, were broken up into four themed programs available both in person and on Zoom. Fellows come from myriad disciplines, including anthropology, journalism, law, environmental science, public policy, public health, and medicine.

Like Bashizada, Osman worked on immigration issues. Interning with the Immigrant Law Center of Minnesota, her home state, she helped provide vital legal support and representation to Somali individuals in ICE custody. Osman conducted research and circulated surveys about detention conditions for Somali detainees in Minnesota’s ICE detention centers — aiming to identify recurring issues and avenues for redress for human rights violations, and to eventually share the data with lawmakers in order to push for policy changes.

Minneapolis has North America’s largest Somali population, which Osman said is overwhelmingly Black, Muslim, and refugees and had been “able to thrive, molding to a Minnesotan way of life.” But she said crackdowns on immigrants during Donald Trump’s presidency put the community in danger.

Osman helped design a survey to gain a comprehensive view of the harms immigration detention has caused the Somali community. Her work involved assisting new clients detained by ICE and conducting fieldwork research studying trends treatment of detained Somalis.

“While the detainees themselves are subject to deplorable conditions and horrible health outcomes, their families are also facing very real and tangible harms,” Osman says. “Our surveys were to build a detailed understanding of the discrimination they’ve been dealing with and build a framework for undetrsanding the national impact.”

Noting that ICE doesn’t have its own separate facilities, she explained how the agency contracts with various jurisdictions.

“The result is that housing federal detainees becomes very lucrative for small counties,” Osman says.

COVID has further complicated things, but it hasn’t stopped ICE from halting deportations. Those deported may have major consequences for Somalia, which is one of the world’s least prepared nations in terms of dealing with the pandemic.”

Hard to swallow

Spoelman, who worked for five years in organic foods certification before law school, discussed human right abuses and land conflicts involving bananas and palm oil. Working last summer with EarthRights International, a nonprofit law firm based in Washington, D.C., she contributed legal research and writing and helped develop litigation strategies to support ongoing cases.

In the 1990s, Spoelman explained, Chiquita began acquiring land from farmers during Colombia’s internal armed conflict. AUC, a powerful paramilitary and drug trafficking group, became known for their brutality and targeted anyone seen as having left-wing views.

“The United States classified them as a terrorist organization,” Spoelman said. “Nevertheless, Chiquita set a deal with AUC to pay them a fixed amount for every box of bananas exported. Banana workers who might strike, union organizers, or small farmers who didn’t want to sell their farms were all suppressed. In exchange, Chiquita was free to produce bananas in an environment free of labor opposition and social disturbances. In short, Chiquita knowingly traded human lives for profit.”

In 2007, Chiquita pled guilty in federal court to funding terrorist organizations and paid the U.S. government $25 million. Spoelman said that while a claim EarthRights International filed on behalf of American victims of Chiquita’s dealings did result in compensation, 200 Colombian victims identified in another civil claim by the organization have yet to be compensated.

She also described the palm oil controversy in Honduras, where Dinant Corporation — which grows African Palm, processes the oil, and harvests other crops — was run violently by its president Miguel Facussé Barjum. Spoelman described how Barjum, one of the richest men in South America before his recent death, ordered his private security guards to confront, intimidate, and take land from peasant farmers throughout Honduras.

In 2009, the International Finance Corporation — part of the World Bank — granted a $30 million loan to expand a Dinant palm oil plantation development project.

“With this new income, Dinant bought military weapons and hit men who murdered, kidnapped, and tortured campesinos fighting for the return of their land,” Spoelman said, adding that over 140 of them have been assassinated since the first IFC loan payment.

“Litigation is one tool we can use to try to address this, but it’s really only effective after the fact,” she said of a 2017 case EarthRights International filed against IFC in federal court. “In every case, it seems like the avenue for justice gets narrower. For both Chiquita and IFC, there were mechanisms in place that were supposed to prevent this from happening. For Chiquita, it was the federal law that prohibited funding terrorists. For IFC, it was their own standard against funding a project known for violence. Neither of these mechanisms center the voices of the communities affected.”

Filling an international void

Helena von Nagy, who clerked in the U.S. State Department’s Office of the Legal Adviser, worked to bolster U.S. support for human rights and to develop the centrality of human rights concerns within international law. Assuming the same duties as a junior attorney, she focused on America’s position on and role in shaping the legal aspects of addressing crimes against humanity — its own and those elsewhere.

In her presentation, von Nagy discussed the International Criminal Court chief prosecutor’s recent decision to deprioritize the investigation into U.S. war crimes and crimes against humanity in Afghanistan by U.S. forces, especially drone strikes. The U.S. could participate in upcoming talks about a potential United Nations treaty on crimes against humanity.

Addressing “a really big gap in international criminal law,” von Nagy said, “There is no convention that addresses national laws, national jurisdiction, and interstate cooperation for crimes against humanity prosecutions. Since crimes against humanity can occur during peacetime, they’re also not covered in various treaties that govern the law of war. So this would be the first treaty to spell out a definition of these crimes for states that haven’t joined the International Criminal Court.”

She noted that one mechanism for interstate cooperation to prosecute such crimes — requiring domestic laws to prosecute them — has been ratified by two-thirds of U.N. members, but the U.S. has not taken an official position on those draft articles.

“My general sense is that the State Department sees an opportunity to push for the U.S. to support and participate in negotiation of these draft articles,” von Nagy says. “The U.S. does care deeply that it doesn’t take on international obligations it cannot actually fulfill.”

Working one on one with clients in the immigration and asylum systems, von Nagy described the frustration of having to navigate within “incredibly restrictive laws” in order to seek justice. Still, she relished working on changing laws so attorneys in the future could face an easier landscape.

“I’m not going to pretend that these draft articles on crimes against humanity will be a cure-all … I mean the U.S. is a party to the Convention Against Torture and that didn’t stop the CIA or the armed forces in Afghanistan,” von Nagy said. “However, a domestic part of a legislation which is required if we join the convention would be a strong basis for convicting people for crimes against humanity … and create new tools for human rights defenders to seek justice and accountability. The first step is a good faith engagement from the U.S. in the negotiation process, and that happens because of attorneys at the State Department.”