By Andrew Cohen

When it comes to paid leave for workers, the United States lags far behind other industrialized nations. That gap, says Berkeley Law Professors Catherine Albiston ’93 and Catherine Fisk ’86, reflects a growing inequality among Americans accelerated by the COVID-19 crisis.

Albiston’s recent article in Contexts, which presents leading social science research, details the impact of an ongoing economic transition from full-time permanent employment with paid leave, health insurance, and retirement benefits to less stable jobs. Albiston and Fisk submitted an expanded version of the article to the California Law Review, and discussed America’s shaky social safety net during a joint online presentation.

“Social policies have not kept pace, shifting the risk of both ordinary downturns and catastrophic events onto workers and their families,” Albiston says. “Low-wage workers in precarious employment are the most likely to lack these protections and the most exposed to risk in the current crisis.”

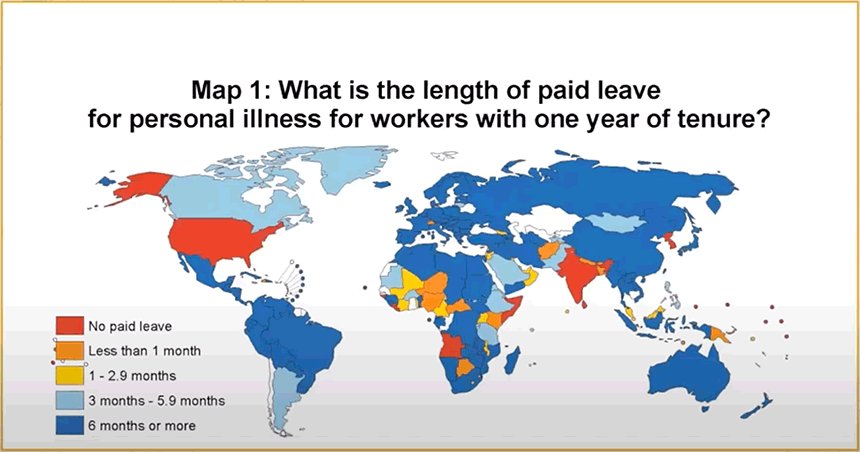

According to the World Health Organization, paid sick leave is particularly vital during crises as its absence forces ill workers to choose between tending to their health or risking their job. Yet until recent emergency measures, the U.S. was an outlier among developed countries in providing no federally mandated paid sick time or paid family leave.

Among the sobering figures Fisk and Albiston presented: a 2018 Federal Reserve study showing that 40 percent of Americans are unable to cover an emergency cost of $400 or more with cash or credit.

The chasm conundrum

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics show that only 16 percent of American private-industry workers get paid family leave through their employer, with more access among highly paid occupations, full-time workers, and in large companies.

Although access to sick leave is broader, private sick leave benefits follow similar patterns of disparity. Having such leave reduces the probability of job loss by 25 percent, studies indicate, and those who lack it are more likely to go to work sick, forgo medical care for ill family members, and experience unemployment.

“Wealthier families are better able to absorb the cost of private caregiving, but lower-paid workers have few options other than providing the care themselves at the expense of their paycheck,” Albiston says. “Two-parent families can share care and earning responsibilities, whereas single-parent families, which are at least as prevalent as dual-worker families, must meet both responsibilities with one adult earner.”

On March 18, the U.S. enacted legislation providing two weeks paid sick leave and partially-paid family leave for up to 12 weeks. The bill covers workers who have been on the job for as few as 30 days, offers prorated pay for part-time workers, and bars employers from retaliating against employees for taking paid leave.

Pay is capped at $511 per day for sick leave, but only $200 or two-thirds pay (whichever is smaller) for family leave. The law excludes employers with 500 employees or more—which constitutes more than half the workforce—permits the Department of Labor to exempt small businesses, and excludes health care workers at their employers’ discretion. The law also expires at the end of the year.

“We see predictable patterns of inequality,” Albiston says. “The idea that we’re going to provide 10 weeks of paid family and medical leave for people taking care of kids who are out of school, but not people who are sick with COVID-19, I can’t understand why that would be the case … And if you’re sick yourself you’re entitled to up to $511 a day, but if you’re caring for someone else you only get two-thirds pay, I don’t understand that distinction. Most care is provided by women, so that lost pay also falls disproportionately on women.”

Fork in the road

The recently-enacted CARES Act includes $1,200 stimulus checks, expanded unemployment benefits, the ability for employees to borrow against their retirement accounts, and incentives for employers to keep people on their payroll. Some states are filling gaps in the Act (California is initiating various programs to protect workers who are excluded), while others are not.

Fisk says the social insurance system emerging from all of this “is mind-bogglingly complex” and that “the patchwork of employer-provided, federal, and state programs is difficult for workers to navigate.”

The complexity may defeat the utility, she explains, if workers and small businesses without access to expert legal advice and bank relationships are unable to obtain the benefits.

“The optimistic vision is that this COVID-19 legislation might be the beginning of a transformation of the welfare state” that brings independent contractors and lower-wage workers into the fold, Fisk says. “The pessimistic view is that the economic depression that probably will result from the pandemic is going to exacerbate pre-existing inequality. We’ve already seen that in who can work from home and who can’t, whose health insurance continues, and disproportionate numbers of African Americans and Latinx people dying of COVID-19.”

With Americans increasingly holding low-wage jobs and over 10 percent employed in the “gig economy” as independent contractors, the professors see COVID-19 shining a brighter light on income inequity.

“While the pandemic is a global emergency, for millions of families the lack of paid leave in the United States has been an emergency for a long time,” Albiston says. “This isn’t a new problem, only one that is newly visible in this simultaneous health care crisis for everyone.”