By Gwyneth K. Shaw

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has considered thousands of allegations over more than 60 years. On Nov. 4, the commission broke new ground, hearing testimony about the 2010 fatal beating of Anastasio Hernandez Rojas by U.S. border agents.

It’s the first time a case about an extrajudicial killing by U.S. law enforcement has been examined by an international human rights body. And it happened because of a coalition determined to fight for justice, including Berkeley Law faculty and students.

CONTENT WARNING: 2010 video of Anastasio Rojas beating by US border agents

“Anastasio’s family decided to bring the case before the Inter-American Commission because the U.S. legal system failed them,” says Professor Roxanna Altholz ’99, co-director of the school’s International Human Rights Law Clinic, who argued at the commission’s hearing.

“This litigation demonstrates that U.S. law and institutions are unwilling or unable to protect the lives of people, mostly people of color, from state violence,” she says.

Hernandez Rojas’ family wants the commission, an arm of the Organization of American States (OAS), to declare the U.S. government violated his rights under the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man, adopted in 1948 by OAS member states, including the U.S. The commission gave both sides 30 days to submit final written arguments; a decision should come sometime next year.

The facts of the case are stark: On May 28, 2010, U. S. Customs and Border Protection officers beat and tased Hernandez Rojas, who had been living in San Diego for decades, at the San Ysidro Port of Entry. He had recently been deported and was attempting to reenter the U.S. to rejoin his family when he was assaulted; the 42-year-old father of five later died from his injuries.

The U.S. Department of Justice declined to prosecute the agents, even though the beating was captured on video. That’s not the only way Hernandez Rojas’ case resembles the 2020 killing of George Floyd by police, Altholz says: Hernandez Rojas suffered positional asphyxia, just as Floyd did when police officer Derek Chauvin knelt on Floyd’s neck for nine minutes while a handcuffed Floyd lay face down. Chauvin was later convicted of murder.

Altholz joined Hernandez Rojas’ case in 2015 at the invitation of his family and the community organization Alliance San Diego, run by Executive Director Andrea Guerrero ’99, Altholz’s law school classmate. They hope their efforts will help make Hernandez Rojas’ death a similar catalyst for change.

“We need to understand how impunity operates on the U.S.-Mexico border,” Altholz says. “The hearing exposed the specific steps taken by U.S. border agents to cover up their responsibility for Anastasio’s death and identified the laws that stack the deck in favor of law enforcement in the United States.

“Unless we can hold U.S. agents and institutions to account, the killings will continue — in fact, 245 men, women, and children have died in fatal encounters with U.S. border agents since Hernandez Rojas’s death.”

At the hearing, commissioners heard testimony from Maria Puga, Hernandez Rojas’ widow; Altholz; Guerrero; and Rafael Barriga, a former Mexican immigration officer who witnessed the beating.

“What they did to my husband was a murder,” an emotional Puga told the commission. “My family is destroyed. My family will never be the same again.”

She asked for an apology, for the United States to reopen the criminal investigation, and for changes to Customs and Border Protection’s use-of-force policies, a crucial factor in the case.

Differing standards

The cornerstone of U.S. law and policy regulating the use of force is the “objective reasonableness” standard, Altholz says. U.S. law permits force, even lethal force, if the officer perceives a threat and even if that perception is mistaken.

But international human rights standards on the use of force are guided by the imperative of protecting the right to life — a supreme, non-derogable right — from arbitrary deprivation by the state, she adds. The 1948 American Declaration requires that state agents only use force that is legal, necessary, and proportional as a last resort.

At the hearing, officials from the U.S. Department of State and the Department of Homeland Security, which oversee Customs and Border Protection, didn’t dispute the facts of the case and offered Puga and the rest of Hernandez Rojas’ family “our sympathies.” But the U.S. government has asked the commission to throw the case out because the family received a $1 million settlement as a result of a 2017 lawsuit.

Altholz bristled at that argument.

“States cannot kill and pay in order to avoid accountability,” she told commissioners. The factual evidence, she said, is overwhelming that the U.S. agents’ “use of force lacked all proportionality because he posed no threat.”

A team effort

In addition to Altholz, Berkeley Law Dean Erwin Chemerinsky and Professor David Oppenheimer also got involved, each writing an amicus curiae brief in the case.

“This is an enormously important case that arises from truly tragic facts. The proceedings before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights are crucial in exposing the failure of the American legal system to deal with unjustified killings by law enforcement in the United States,” Chemerinsky says. “Roxanna Altholz and our International Human Rights Law Clinic have done a superb job in litigating this case.”

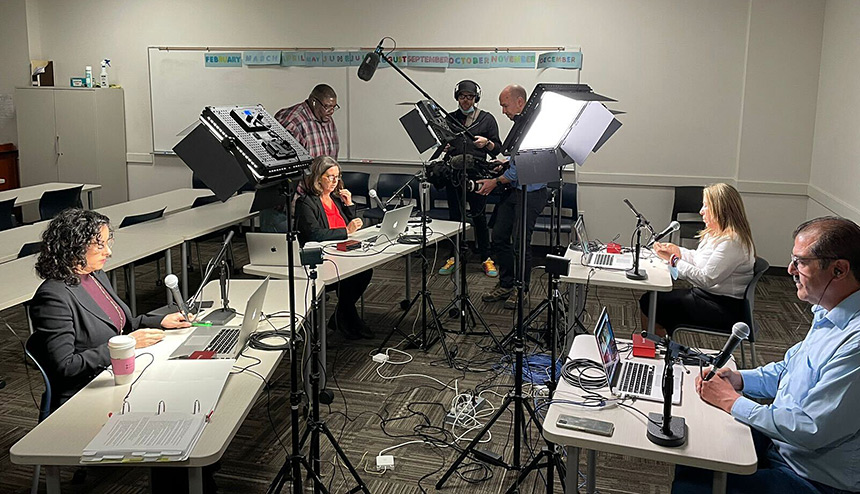

A stream of clinic students have also worked on the case over the years, including several who helped prepare materials for the commission hearing and were in the room when Altholz, Puga, Guerrero, and Barriga testified via Zoom.

Maïmouna Diarra ’23 says one of her most profound experiences while supporting the case was to write declarations on the petitioners’ behalf. Their purpose is to support the arguments with compelling personal testimony while also giving declarants a platform to truly describe how the event at hand affected them and their lives.

“I was able to help write the declarations of Anastasio’s two eldest children,” Diarra says. “Although emotionally difficult at points, it was such an honor to be able to help them put into words the impact of their father’s death on them as individuals but also on their family. I felt lucky to help them tell their story.”

Diarra, Gabriella Lanzas ’24, and Nicole Waddick ’23 all say they’ve been particularly moved by the experience of working with Puga.

“Maria Puga is one of the strongest individuals I’ve ever had the privilege of meeting,” Lanzas says. “I drafted her declaration, and she made that a very easy job because her story, her statements, and her perspective are naturally powerful.”

No matter how well you know the facts of the case, Diarra says, it’s impossible to truly understand the pain suffered by Hernandez Rojas’ family.

“Maria lost her life partner, the father of her five children, and her best friend in the most gruesome and heartbreaking manner; of course, she hurts and yearns for him every day. And yet, before even hearing her testify, when I met Maria for the first time, I was taken aback by her grace and absolute power,” Diarra says. “She is a small woman in physical stature but so immensely strong, resilient, and determined. She possesses such warmth and gratitude for her community and those who have fought alongside her.”

Lanzas says her work on the case was not just a gratifying challenge, but also changed her perspective on what it means to be a lawyer.

“I think receiving a legal education and grasping the skill of legal analysis is very powerful, and I feel that power sitting in a Berkeley Law classroom every day. But participation in this clinic has taught me that classroom legal analysis is only one piece of the puzzle needed to create real, lasting justice,” she says. “Advocacy, organizing, politics, media, foreign affairs, networks, and the public’s interest are just as important to this case. I intend to implement that more comprehensive view of a path to justice in my future practice.

“I am grateful and honored to have played a small part in this historic hearing.”

Learn more about Anastasio Hernandez Rojas, his family, and the fight to hold U.S. officials accountable on this webpage, which features legal documents, media coverage, and videos.

Working in her native Spanish with other Latina lawyers made the experience even more rewarding, Lanzas says. She, Diarra, and Waddick say they got amazing up-close views of how Puga, Altholz, and Guerrero battled to bring the case to the commission, through the emotional power of the story and the available legal levers.

“Watching Maria go face to face with the U.S. government was one of the most awe-inspiring experiences I’ve ever had. She carries herself with a strength and a grace that you can feel the minute you walk into a room with her,” says Waddick, who is in her second year of working on the case. “It was such an honor and a privilege to be in her orbit, as well as Andrea and Professor Altholz’s, whose passion and conviction for the movement this community is building really gives you faith that use-of-force standards and investigation standards can and will be reformed — even in the face of some pretty formidable obstacles.”

All three students call the experience among their best in law school, noting that it’s provided critical grist for their future career aspirations.

“Having the chance to be a part of the community that the Hernandez Rojas family, Alliance San Diego, and the clinic have built reminded me why I came to law school and really affirmed my desire to work in human rights work after graduation,” Waddick says. “Seeing the huge range of advocacy strategies this team has pulled together and the ways in which Professor Altholz and Andrea, along with the rest of the team, so fiercely advocate for their clients, has shaped my understanding of what lawyering can look like and shown me how to bring a creative, movement-building, and human aspect to the law.”

Diarra wholeheartedly agrees.

“Having the opportunity to support this case has reaffirmed my desire to use the law and other forms of advocacy as tools for good; tools for reimagining and fighting for a more just world.”