By Andrea Lampros

More than three decades ago in a forensic laboratory in Sao Paulo, Brazil, Berkeley Law’s Eric Stover held the bones of the infamous Nazi doctor Josef Mengele.

More than three decades ago in a forensic laboratory in Sao Paulo, Brazil, Berkeley Law’s Eric Stover held the bones of the infamous Nazi doctor Josef Mengele.

“Standing there looking at the skeleton, I thought, how could it be that this war criminal, who fled Auschwitz in 1945, could end up here on the other side of the earth? And what about all the other Nazis who were walking free in Latin America, where were they and why hadn’t they been caught?”

That question stirred by Mengele’s bones stayed with Stover as he went on to investigate wartime atrocities committed by political and military leaders in more than a dozen countries. Investigations took him to Srebrenica in 1996 where, two years earlier, Bosnian Serb leaders Radovan Karadzic and Ratko Mladic had overseen the massacre of 8,000 men and boys in one of the worst atrocities on European soil since World War II; and then to war-torn Iraq where he and forensic anthropologist Clyde Snow uncovered graves of Kurdish victims of Saddam Hussein’s “Anfal” campaign in the late 1980s; and, more recently, to northern Uganda to interview child soldiers who had escaped from Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army.

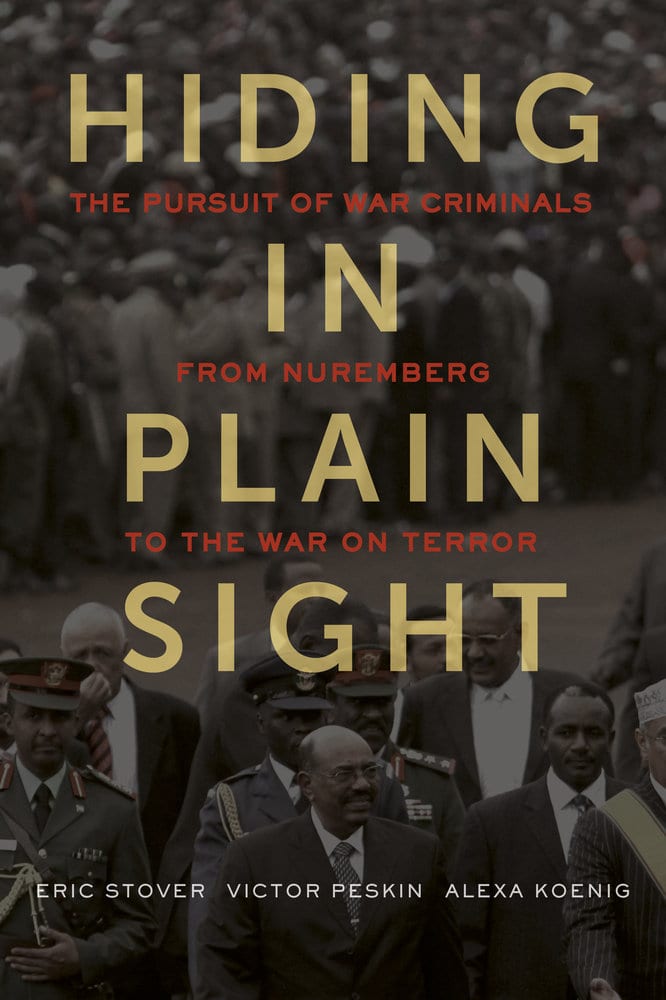

Six years ago, Stover teamed up with Berkeley Law’s Alexa Koenig and Arizona State’s Victor Peskin to try to understand why so many states ignore their legal obligations to arrest and try war crimes suspects. The result is the just-released Hiding in Plain Sight: The Pursuit of War Criminals from Nuremberg to the War on Terror (University of California Press).

Telling one story at a time, the authors follow the flight—and on again, off again pursuit—of war criminals throughout modern history: from Nazis to today’s high-level suspects, including President Omar al-Bashir of Sudan, Liberian warlord Charles Taylor, and the al-Qaeda leader Osama bin-Laden. They probe the ebb and flow of political will to arrest and try perpetrators of war crimes, and they culminate in the sea change prompted by the war on terror when the U.S. shifted from vocal proponents of international law to explainers of “American exceptionalism”—justifying the use of killer drones, black sites, and torture.

The book opens with Mengele, known as “the Angel of Death,” and his Nazi counterparts, Adolf Eichmann and Klaus Barbie, slipping into the chaos of post-war Germany.

Unlike other SS officers, Mengele avoided having his blood type tattooed onto his arm or chest (to keep his skin unmarred). Such a tattoo would have been a dead giveaway to the Americans that they had a potential war criminal on their hands. Instead, the Auschwitz doctor fled on a so-called “rat line” of safe houses set up by Nazi sympathizers to the Italian port of Genoa, where he boarded the North King, a passenger ship bound for Argentina.

Through Argentina, Paraguay, and finally Brazil, Mengele lived and worked, even managing a small farm where he skillfully treated sick farm animals, employing techniques honed on the hideous experiments he performed on humans during the Holocaust.

Although aware and fearful of the Nazi hunters on his trail, Mengele lived simply, but with relative freedom, until he drowned while swimming in the ocean near Sao Paulo in 1979.

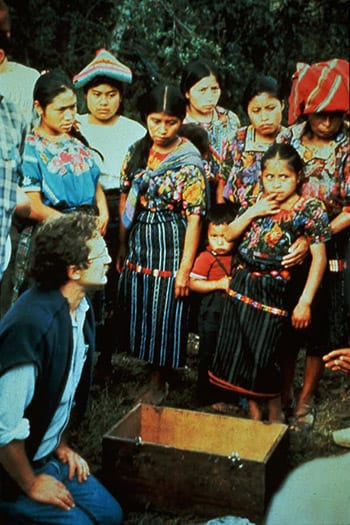

Stover—the first to engage U.S. forensic scientists in international war crimes investigations—traveled to Brazil as part of a team of American and German scientists tasked with their Brazilian colleagues to examine remains buried under the name of Wolfgang Gerhard, but believed to be those of Josef Mengele. Analysis of the skeleton’s gapped teeth and a fractured hip, and ultimately, DNA evidence, proved that the bones were in fact those of Josef Mengele.

The case of Nazi Adolf Eichmann, infamous architect of the “Final Solution,” was more satisfying for those seeking justice. Instead of seeking extradition, the Shin Bet (akin to the Israeli FBI) abducted him off a street in the suburbs of Buenos Aires, where he had fled in the aftermath of World War II. While the kidnapping was illegal, the Israeli court that tried him adhered to the principle of male captus, bene detentus (badly captured, rightly detained), which permits court cases to proceed even when a suspect is captured illegally.

In December 1961, Eichmann was successfully convicted of numerous international crimes against humanity, and more, for his role in the Holocaust. His trial, which was broadly televised, spurred a renewed interest in using courts to account for violations of international law.

Fugitives of the Balkan Killing Fields

In early 1996, just after driving west with his wife, Pamela Blotner, to make a new home in Berkeley and direct Berkeley’s Human Rights Center, Stover traveled to Bosnia. He worked with a team of investigators assembled by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) to investigate war crimes committed by forces under the command of Karadzic and Mladic.

At the time, both men were living openly in Bosnia despite the presence of more than 60,000 NATO troops. The strategy of U.S. military commanders and their European allies was to keep the peace by a massive show of force, even if it meant cooperating with warlords. That policy eventually changed, and Karadzic was finally apprehended in 2008, followed by Mladic’s arrest three years later.

Just last month, more than two decades after the Srebrenica massacre, the ICTY sentenced Karadzic to 40 years in prison for genocide and crimes against humanity. (Read CNN article with Stover comments on case).

Mladic, who was Karadzic’s first in command, will learn of his verdict early next year. (Stover, Peskin, and Koenig wrote a story for Foreign Policy, upon the Karadzic decision last month.)

“Making arrests boils down to political will,” Stover said, echoing a central theme of the book. “In order to have international justice, governments must have the fortitude to enforce arrest warrants. Yet many states ignore this legal obligation because they fear it will imperil their political or security interests.”

Omar al-Bashir, whose image appears on the book’s cover, is a case in point. The sitting Sudanese president is charged by the International Criminal Court with genocide and crimes against humanity for the killing of hundreds of thousands in Darfur, and yet he travels freely throughout Africa. Al-Bashir touched down in South Africa in 2015 without incident or arrest.

Unbound by the Law

Author Alexa Koenig, executive director of the Human Rights Center, whose research spans military detention, Guantánamo, and the use of drones in the “war on terror,” said that Hiding in Plain Sight takes a critical look at American exceptionalism.

“We tell the story of post-9-11 U.S. policy when the use of drones and illegal detention indefinitely changed our relationship to international law,” Koenig said.

The authors relate the story of Abu Zubaydah, operations commander of al-Qaeda, who was flown to a so-called “black site” in Thailand and Poland. He is believed to be the first detainee in the war on terror subjected to torture or what the Bush Administration called “enhanced interrogation techniques” including waterboarding, pro-longed stress positions, sleep deprivation, forced nudity, and beatings. The Washington Post later reported that senior U.S. officials were concerned that “not a single significant [al-Qaeda] plot was foiled as a result of Abu Zubaydah’s tortured confessions”

In the book’s Epilogue, Stover, Peskin and Koenig quote former ICTY prosecutor Louise Arbour on the recent shift in U.S. policy: “The entire system of abductions, extra-legal transfer, and secret detentions is…a complete repudiation of the law and the justice system,” she said. “No state resting its very identity on the rule of law should have recourse or even be a passive accomplice to such practices.”

Stover said Hiding in Plain Sight ends at this pivotal place—where the under-resourced International Criminal Court remains bound by the law, pursuing an elusive justice, while states, including the United States, ignore the very laws they promulgated.

“Until this situation is rectified,” the book concludes, “murderers will get away with murder, and torturers will retire with pensions.”