By Susan Gluss

In her new book, Habeas Corpus in Wartime, Professor Amanda Tyler offers a searing look at episodes in U.S. history when the federal government undermined its citizens’ legal rights during times of war.

Tyler focuses on the constitutional protection against unlawful imprisonment, or the writ of habeas corpus—and the government’s power to suspend it during conflicts. Her critique reveals an incremental breakdown of habeas corpus, starting with the American Revolution and continuing through the war on terror.

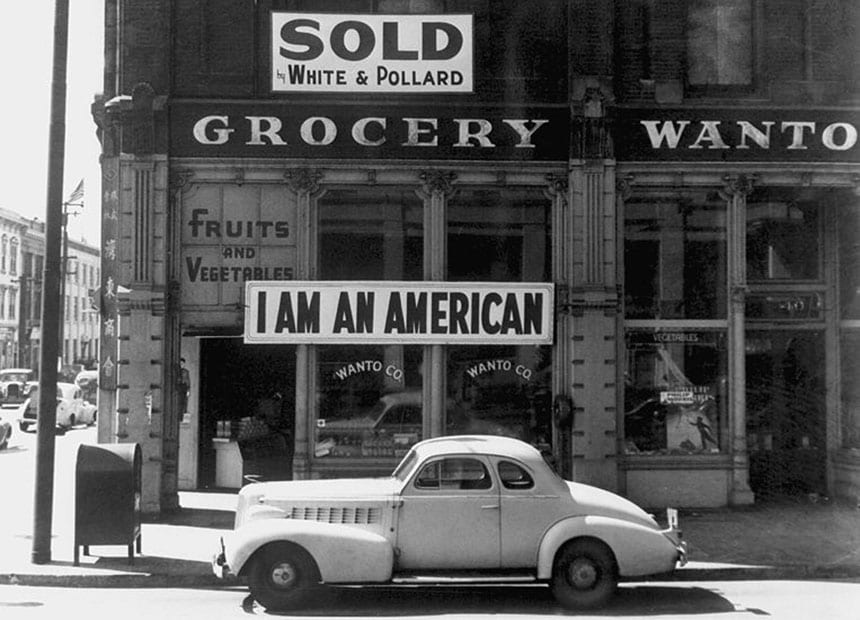

Taking sharp aim at the most egregious instance of illegal detention, the internment of Japanese American citizens during World War II, Tyler questions the extent of executive power that enabled that chapter in U.S. history.

When she joined Berkeley Law’s faculty in 2012, Tyler brought a wealth of experience working as a litigator, professor, and judicial clerk for Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg at the U.S. Supreme Court and Judge Guido Calabresi at the Second Circuit Court of Appeals. Her research and teaching interests include federal courts, constitutional law, civil procedure, and statutory interpretation.

Tyler recently sat down with Susan Gluss for a conversation about her book. The copy has been edited and shortened for the web.

Susan Gluss: Why the book? Why the topic?

Amanda Tyler: I started writing about executive power in wartime in the wake of 9/11, when hard questions arose about civil liberties and national security. These same questions had come up in the past with varying answers and legal outcomes. I wanted to recapture that history to shed light on current debates.

You focus on habeas corpus, a constitutional protection against unlawful imprisonment, and the government’s power to suspend that right in times of invasion or rebellion. How did the interplay of those two provisions—habeas corpus and the Suspension Clause—change over time?

The legal framework was almost uniformly consistent during early English and American history. It’s in the 20th century where the law starts to break down and chart a new course, specifically with the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

Members of then-President Roosevelt’s administration knew that the internment of citizens was a blatant violation of the habeas provision in the Constitution, known as the Suspension Clause. That highlights how entrenched the legal framework had been up until that point. By the end of the war, the courts were sidestepping these issues, and the Suspension Clause fell by the wayside.

We’re left with a bad precedent: that it’s acceptable to detain citizens in matters of national security—even if they’re not charged with a crime. That would have shocked the founding generation. The whole point of the Suspension Clause was to limit the government from doing this very thing.

How did Roosevelt get away with it?

On the home front, political support for internment was quite robust. And the Roosevelt administration wanted to do whatever it could to win the war. That meant giving carte blanche to the war department.

Unfortunately, it’s not only an example of bad precedent, but it also sheds great doubt on the executive branch’s ability to self-police in times of war or national crisis. Roosevelt’s inner circle said, “this interment violates the Constitution, we cannot do this,” and that included the secretary of war and the attorney general. It didn’t matter; the policies went forward.

What role did the courts play?

Only the case of Mitsuye Endo challenged the internment directly. The Supreme Court gave her a narrow victory without addressing the constitutional issues raised in the case and then held its opinion until after the 1944 election.

The courts during World War II, including the U.S. Supreme Court, were extensively deferring to the executive branch and its broad assertions of national security. There wasn’t the pushback that I’d like to think we would see today.

What about previous wars?

During the American Revolutionary War, the British tried very hard to behave legally in its treatment of rebel prisoners held on English soil.

During the Civil War, President Lincoln famously claimed the mantle of suspension on his own, and as I argue in the book, that was wrong. But he recognized that the government could not simply detain persons who were protected by domestic law. He believed a suspension was constitutionally necessary to detain Confederate soldiers outside the criminal process.

There was absolutely no factual basis for any argument that the needs of national security required displacing and ultimately incarcerating Japanese Americans.

World War II is a severe example that should give us pause. There was absolutely no factual basis for any argument that the needs of national security required displacing and ultimately incarcerating Japanese Americans.

How does the current administration approach executive power?

In the travel ban litigation, the Trump administration has been arguing that it should receive deference on all decisions implicating national security. It wants final say over what that requires, and argues that the courts should never second-guess it. But the World War II episode is a cautionary tale of what happens when courts defer to the government regarding national security.

What if a president needs to act quickly in the face of a global threat?

The Constitution does permit the executive branch to make certain decisions without being second-guessed, such as the power to recognize foreign states.

But when we talk about individual liberty, that’s an area that the Constitution has always thought to be within the province of the courts. Even in wartime, there are certain issues that aren’t given over wholesale to the executive branch—and the deprivation of individual liberty would top that list.

What are courts for if not to protect people from unconstitutional arrests? Some say that’s the most important thing courts do.

Did the framers take war into account?

There’s debate about this point. I side with Ex parte Milligan, written in the wake of the Civil War. The Supreme Court found that the Constitution was written for both war and peace, and it’s supposed to govern the same in both circumstances.

I think that has to be right. The Constitution may not be the most flexible document, but it certainly contemplated that war was a possibility. It includes certain provisions, including the Suspension Clause, to create a legal framework for government operations in times of war. To say that we should discard all of that because of a threat to national security or a state of war disregards the very thoughtful planning that went into drafting the Constitution.

Has the Supreme Court gone too far in constricting individual liberty?

After the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing, prominent members of Congress, including Sen. John McCain, suggested that the surviving suspect—a naturalized American citizen—could be treated as an enemy combatant. Many labeled him a terrorist.

Indeed, in the 2004 Hamdi v. Rumsfeld case, the Supreme Court permitted the government to hold citizens in military detention as enemy combatants during the war on terror.

That struck me as wrong and at odds with history. In the book, I try to explain why this concept of a so-called “citizen enemy combatant” is in conflict with the Constitution. It’s not something that the founding generation would have countenanced.

Based on our constitutional history, the current state of the law is incorrect. We’ve taken a wrong turn, starting with the Japanese American internment, and we’ve been straying off course ever since.