By Gwyneth K. Shaw

When Ecology Law Quarterly debuted in the winter of 1971 — seeded with $35 in stationery money from a skeptical Dean Edward Halbach — the environmental movement as we know it was just beginning to find its footing. Silent Spring, Rachel Carson’s searing call to action, had been published only nine years earlier. Earth Day and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency were in their infancy.

Five decades later, the student-run journal sits at the pinnacle of the academic landscape, publishing groundbreaking environmental law scholarship four times a year. (In 2008, the print journal gained a digital sister, Ecology Law Currents, for shorter-form articles and analysis.)

“ELQ has been a flagship for the environmental law movement for 50 years now,” says Berkeley Law Professor Daniel Farber, himself a titan in the field and a member of the journal’s faculty advisory board. “It has been a leader in exploring new issues as they emerged, like climate change and environmental justice. Environmental issues still don’t get the coverage they deserve from the older student law reviews, so as a top environmental law review ELQ is the place to go for the latest thinking.”

The journal has also been a public symbol of Berkeley Law’s deep commitment to environmental law, Farber says, and key to the school’s top ranking in the field from U.S. News & World Report. Along with the school’s Center for Law, Energy & the Environment and Environmental Law Clinic, ELQ forms a hub that draws faculty and students from around the nation.

In California, which has long been a national pioneer in preserving land, pushing for cleaner water, and fighting climate change, ELQ’s reach is particularly expansive.

“It’s been the pillar of our unique student community, and the starting point for many leaders in the field in California and the nation,” Farber says. “It’s also trained generations of students who have gone on to illustrious careers as environmental lawyers.”

Among those is Professor Claudia Polsky ’96, who once helmed ELQ and now directs the Environmental Law Clinic and serves as a faculty advisor for the journal.

“ELQ was a key reason many of my 1990s cohort chose Berkeley Law,” she says. “The journal was integral to our law school experience: the editorial aspects; the gatherings around a vat of guacamole for ‘Guac Fests’ to celebrate each issue’s publication; the trips to Yosemite, which introduced us to the splendors of California; the mentorship from more senior environmental law students; the social community.

“The 1995-96 ELQ book review editor even officiated at my wedding!”

A pause to celebrate and reflect

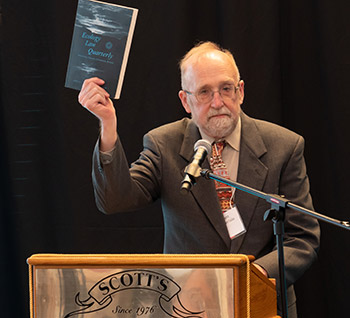

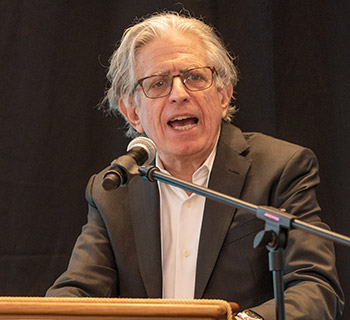

The sense of community was palpable at ELQ’s annual banquet in April, which served as a celebration of the journal’s 50th anniversary. Faculty, students, policymakers, and a decades-spanning array of alumni joyfully toasted the milestone. Robert Bullard, considered the father of the environmental justice movement, was honored with the journal’s Environmental Leadership Award.

The banquet was underwritten by Deanna Ruth Rutter ’72, the first woman to serve as ELQ‘s editor-in-chief, so all proceeds from the event and accompanying silent auction went to energy and environmental law student programs.

Christina Libre ’23 and Katalina Hadfield ’23, ELQ’s current co-editors-in-chief, say the banquet was a thrilling testament to the journal’s powerful role — and further inspired their ongoing mission.

“It was special to find myself in a room full of professors, practitioners, authors, and alums who so obviously cared about the journal with the same depth of feeling as my peers and me,” Libre says. “ELQ has been such a positive fixture in my life over the past couple of years, and it was moving to hear that decades of predecessors have felt the same. Kat, the current board, and I take the responsibility of sustaining and improving upon that legacy seriously.

“It is obvious to me that ELQ is beloved by a lot of people, in addition to being regarded as a real leader in scholarship on environmental law.”

“It was so heartwarming to see the vast and deep community that ELQ has fostered over the past 50 years,” Hadfield says. Watching old friends and colleagues reconnect made her look forward to joining the journal’s thriving alumni network after she graduates.

“I came to Berkeley Law to study environmental law, so joining ELQ seemed like a natural fit,” she says. “However, it’s the community that has kept me here and motivated me to take on the position I have today. This group of people care so deeply about our planet, and it is an honor and a privilege to run this journal with a group of smart, driven, caring, and thoughtful students all working toward a common, meaningful goal.”

Elevating environmental law

Professor Holly Doremus ’91, a current faculty advisor, calls her time on the journal the most important element of her experience at Berkeley Law. Like Hadfield, she already knew she wanted to be in the field when she arrived on campus, but ELQ’s role as a place to meet like-minded students was hugely important, since Doremus was older and had a different background than most of her class. (She also notes “ELQ has the best T-shirts at the law school, year after year,” and says she still has a few classics in her closet).

The legacy of the journal has shaped Berkeley Law, too, she says.

“It has had a big influence on our environmental program, providing a venue for student organizing to push the faculty in the direction of expanding the program and making sure it constantly evolves to cover the areas they are interested in as those change,” Doremus says.

As a professor, she tries to feed student excitement about environmental issues and the challenges and possibilities of addressing them through law. In her Environmental Law Writing seminar, which gives students a chance to work on pieces for ELQ’s Annual Review of Environmental and Natural Resource Law, she works with them to see legal writing as an exercise in effective communication — and maybe inspire them to pursue their own academic careers.

“I hope to get them to see law as something that constantly changes and to equip them to be active and effective participants about the directions it should take in the future,” Doremus says.

The next 50 years

As the urgency of climate change continues to increase, ELQ and its mission has to adapt with it. Farber sees the online forum as a particular avenue for growth, especially for legal and policy analysis of major issues.

“I’m sure that the journal will remain on the cutting-edge of environmental thinking,” he says. “I also hope that the journal will become increasingly international in its scope, expanding its influence globally.”

Libre and Hadfield recognize that they are crucial to that future, both with their roles at the journal and their work in the larger field. They hope to keep ELQ as a place for intellectual rigor, warm community, and commitment to environmental justice for years to come.

“There is no denying that environmental challenges are becoming more dire by the day, especially under the climate crisis. There is such an enormous need for creative, ambitious thinking in environmental law and policy, and I hope for ELQ to originate a lot of the visionary thinking we need to take on those challenges,” Libre says. “I especially hope that that leadership emphasizes environmental justice and thoughtfully works to right the ways that mainstream environmental movements have excluded and shifted environmental burdens to BIPOC communities, the poor, and others.”