By Andrew Cohen

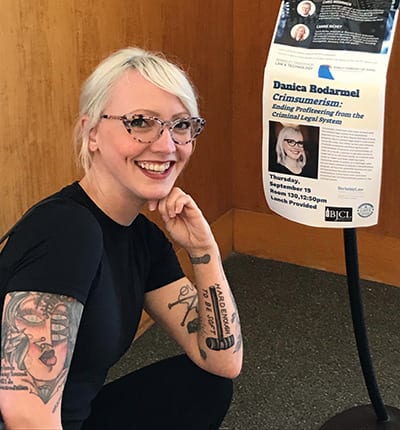

As the role of private companies in the jail and prison systems keeps expanding, Danica Rodarmel ’17 sees a corresponding escalation of injustices.

“Increasingly, Americans who have contact with the criminal legal system find themselves deprived not just of their liberty but also of their property,” she says. “A lot of criminal legal debt is now owed not only to the state, but also to a vast network of private companies profiting from the criminalization of poverty and communities of color.”

As a result, she adds, incarcerated people who want to make bail or call their family, parents anxious to make sure their child has basic necessities while incarcerated, or families navigating private probation face the additional potential hardship of spiraling debt.

Rodarmel helped organize a recent “Crimsumerism” conference at Berkeley Law that tackled how consumer protection law can help alleviate these burdens. She created the first free consumer protection bail clinic as an Equal Justice Fellow, and last year introduced two bills—one to rein in bail abuses and one to address price-gouging in prisons and jails—in the California State Legislature.

She also coined the term “crimsumerism,” and views involving private companies in the prison industrial complex as “another way in which those in the system are subjugated.”

Presented by the Berkeley Center for Consumer Law & Economic Justice, the symposium convened students, lawyers, researchers, people with direct experience in the prison system, and family members of those who have been incarcerated.

“There was a palpable energy and commitment to justice in the room,” says center Director Ted Mermin ’96. “Everyone there was focused on coming up with new ways to apply existing consumer protection laws and develop new policies in order to reduce abuses in the legal system.”

Profiting from incarcerated people and their support networks

Panelists described how private equity-owned companies dominate core aspects of prison life, including telecommunications. When it comes to phone calls and video communications, the family members and support systems of incarcerated people foot the bill—paying anywhere from $1.44 to $17.80 for a 15-minute phone call in California.

While incarcerated, Amika Mota could write letters to her older two children—but for her youngest, “it was a whole different deal to be able to hear my voice. That was our way of staying connected.”

Mota described how timers were set for how long each child could talk to her. She called just once a month “because I was expecting (others) to take care of my kids,” she said. “I couldn’t also ask them to pay for these ridiculous expensive phone calls.”

Some jurisdictions are now even reducing human contact between incarcerated people and their children, replacing in-person visits with video communications—which provide yet another source of profit. “There’s nothing that can reassure a child of their connection with someone more than touch,” Mota said. “It’s such a human experience. The idea of replacing human touch and connection with a video screen is crazy.”

Jesse Vasquez, formerly incarcerated at San Quentin State Prison, noted that his release hinged on him entering state-run transitional housing.

“They get paid by how many people are in the beds,” said Vasquez, who was editor-in-chief of the San Quentin News. “If I can’t go to work because I have to go to this program first, it means that people are making money off of me while I don’t get to make money.” He called the criminal justice system “a control mechanism designed for profit. Everyone who falls into these cracks is just collateral damage.”

Bailing on bail

Advocates also addressed problems in the bail bonds system, describing how co-signers are regularly misled about bond terms. A recent Southern Poverty Law Center investigation found a widespread practice of extortionate behavior by bail bond companies.

“They routinely insist that consumer protection laws don’t apply to them,” Rodarmel said.

University of Minnesota Professor Josh Page, who worked as a bail bond agent for a year to understand the industry, described an “incestuous relationship” between bail bond companies and criminal defense lawyers that funnel business to one another.

Panelists also lamented how cash bail strips already sparse resources from low-income communities and destabilizes families (60 percent of people in jail cannot afford to make a bail payment).

They pointed to legislative responses such as California Senate Bill 10, up for referendum in November 2020. The bill would eliminate cash bail and change California’s pretrial release system so that detention is based on risk, not financial resources.

“This conference is what the Berkeley Center for Consumer Law & Economic Justice is all about: bringing together people from different backgrounds to focus on solving problems and enhancing justice,” Mermin says. “In fact, I’d say that’s what Berkeley Law, at its heart, is all about.”