By Gwyneth K. Shaw

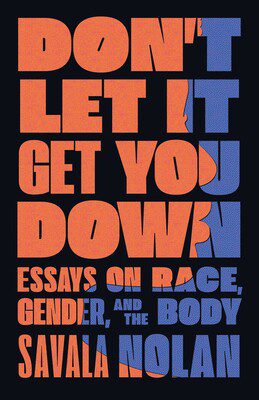

In the new essay collection Don’t Let It Get You Down: Essays on Race, Gender, and the Body, Savala Nolan ’11 fixes a keen and critical eye on some of the most complex issues of our time, processed through the lens of her own experiences. From her body to her family — past and present — to the perception-shaping forces of pop culture, Nolan’s observations feel deeply personal and broadly applicable at the same time as she mines the intersections of race, class, and gender.

The book is garnering rave reviews: It’s “a standout collection” and a “beautiful, brutally rendered narrative,” Tressie McMillan Cottom wrote in The New York Times. Kirkus Reviews declared it “an eloquently provocative memoir in essays…fierce and intelligent.” And critics have compared Nolan’s writing to the work of heavy-hitters like Roxane Gay, Ta-Nehisi Coates, and Claudia Rankine.

Nolan, the executive director of Berkeley Law’s Thelton E. Henderson Center for Social Justice, has also published essays in Time, Vogue, Harper’s Magazine, and other publications, and served as an advisor on race issues for the Peabody Award-winning podcast “The Promise.” She discusses the book below.

Q: There’s a lot of interplay between the personal, the historical, and the political in these essays. Now that they’re united in a collection, do you feel there’s an underlying theme?

Nolan: The essays in this collection are bound together by the body because the body is where the personal, the historical, and the political collide. We experience the definitional categories of our lives — race, class, gender, and more — through our bodies. There’s no getting away from our bodies, and over the course of our lives they become the site of knowledge and epiphany, of humor and grief, of truth but also lies. Each essay wrestles with some aspect of this reality.

I talk about my own body, of course, but also other people’s bodies, too — the bodies of white men I’ve known, from people I wanted to date to terrifying skinheads I once encountered. I write about the large, dark body of my Black father, and compare it to the body of my white mother — what did those bodies mean for the trajectory of their lives, and for how they approached parenting? I talk about female bodies, about fatness, about thinness, and so on. The essays are all corporeal in that way.

Q: How did your time as a student at Berkeley Law influence this book, and what might current students take away from reading it?

Nolan: This book lives and breathes identity: Blackness and whiteness and Mexicanness; womanhood and motherhood and being a daughter; class identity; fat identity, and so on. I hope reading my book reminds students they should not and, in fact, cannot leave their identities at the law school door. Nor should they let go of the knowledge, be it empirical, experiential, heart-based, or instinctual, that their identities give them.

There is no neutrality in law or in law school, but we run into trouble when we act like there is; when I was a student, way back when, there was a sense that we were supposed to think of the law as something neutral, and adopt a posture of neutrality, when in fact the law is simply codified opinions and preferences, and a posture of neutrality won’t serve any lawyer who is working for social justice. Students, especially students from communities that have been systematically excluded and marginalized, do not need to assume a stance of neutrality, nor should they accept the unspoken idea that the law itself is neutral. I hope that, in some little way, seeing me lead with identity and its richness inspires students to hold tight to who they are and where they come from.

There is no neutrality in law or in law school, but we run into trouble when we act like there is; when I was a student, way back when, there was a sense that we were supposed to think of the law as something neutral, and adopt a posture of neutrality, when in fact the law is simply codified opinions and preferences, and a posture of neutrality won’t serve any lawyer who is working for social justice. Students, especially students from communities that have been systematically excluded and marginalized, do not need to assume a stance of neutrality, nor should they accept the unspoken idea that the law itself is neutral. I hope that, in some little way, seeing me lead with identity and its richness inspires students to hold tight to who they are and where they come from.

Q: You write movingly about trying to uncover some of your family’s racial history, from the horrific murder of your great-great-grandmother by white supremacist vigilantes in Texas to the painful process of pulling back the curtain on your family’s history as slaveholders. Can you talk about that journey a bit, and why it’s so important to unveil these truths and make them part of the larger historical narrative?

Nolan: The journey was and is a bumpy one. I just wanted to understand myself and my family better, but what that actually meant was absorbing some brutally difficult information, like that my white forebears were human traffickers during chattel slavery. Or that my second-great grandmother was murdered, in her home and while visibly pregnant, by racist, self-styled law enforcement. I was interested in the stories of the people involved, and I wanted to understand what happened to them. But I was equally interested in the process of learning their stories, in how we come to know this kind of information and how we figure out what to do with it when we live in a culture that doesn’t like to deal with race or racism.

So I wrote about what it was like to work with librarians and map specialists and genealogists to authenticate the information my aunts and dad told me. I write about what it’s like to have friends who know about similar history in their families but who don’t want to dive deeply into the information. I write about how my own racialization and racial education impacts my ability to see my family members clearly, and to see the people we enslaved clearly, and perhaps even to see my own role as a person living on occupied land clearly.

The process is ongoing. I’m still sorting through what I’ve learned, and am still doing research to learn more.

Q: There are a lot of hard moments in this book, and yet there is an electrifying combination of defiance and optimism running through these essays. What do you want readers to take away from them?

Nolan: First, thank you for that wonderful compliment! I hope readers get to the last page and experience two things. First, the sense that they’ve brushed up against truths they didn’t know existed; or truths they knew existed but didn’t have words for. Both of those experiences call us to engage with a bit of defiance and optimism.

Second, I hope they come away with a deeper appreciation for the work their body is doing in our culture. Meaning, a deeper appreciation for how the political, historical, and personal collide in their bodies, and what that means for how they interact with other human beings and how they understand the story of their lives.

My body, with its “in-betweenness,” is somewhat different than many people’s bodies, and that gives me particular insights; but we all have bodies, and therefore we’re all implicated in the systems of race, gender, and class that choreograph our culture. We can all relate, on some level, to being liberated, or empowered, or made safe, or made unsafe by our bodies, by what other people make of them. We can all relate to the frictions and joys that emerge when we move through the world as embodied beings.

So I hope all readers feel truth in the book, whether it takes the form of feeling seen and validated, or of revelation and insight.