By Sarah Weld

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, Berkeley Law’s Death Penalty Clinic released its first-ever report, finding that racial discrimination by prosecutors — particularly against Black people — is a consistent feature of jury selection in California.

That report, Whitewashing the Jury Box: How California Perpetuates the Discriminatory Exclusion of Black and Latinx Jurors, supported a California bill that significantly changed the procedure governing peremptory challenges. It eliminated the requirement that the party objecting to the challenge prove intentional discrimination, and requires courts to consider implicit bias when jurors are excluded.

Now four years later, the clinic has published a follow-up report, Guess Who’s Coming to Jury Duty?: How the Failure to Collect Juror Demographic Data Contributes to Whitewashing the Jury Box, which expands its racial justice research and advocacy by cataloging the states that gather prospective jurors’ self-identified race and ethnicity — and those that do not.

Clinic Co-Director Professor Elisabeth Semel, who wrote both reports along with students, says the 2020 bill is yielding more diverse juries. Currently, however, there is no way to reliably measure the legislation’s effectiveness.

“The primary impetus for the report was the realization that California didn’t have the data necessary to ascertain whether, empirically, new jury selection procedures are having an effect on the composition of seated juries,” says Semel. “We see and hear about changes, but it’s anecdotal.

“As it stands in California, we cannot answer these questions: “What is the racial and ethnic composition of prospective jurors responding to a group of summonses? What is the composition of the panel of potential jurors entering the courtroom? And who is sitting on the final jury?”

Semel, clinic paralegal Lauren Havey, and students Casey Jang ’23, Willy Ramirez ’23, and Yara Slaton ’23 set out to find if — and how — other states are collecting prospective jurors’ self-identified race and ethnicity. They wondered, Semel says, “Are we an anomaly compared to other states? If other states do it, how do they do it?”

Students conducted extensive research on the phone and online, including researching laws in different states, tracking down jury questionnaires and data collection policies, and reviewing state standards and guides on jury management.

No consistency or cohesion

Slaton says she was struck by how “wildly inconsistent the practices are in this country, which means defendants are getting wildly different jury experiences.”

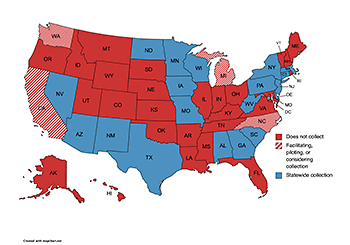

The students found that 19 states, the District of Columbia, and federal district courts collect race and ethnicity data either from source lists or directly from prospective jurors. In 16 of those states, the information is available to trial judges and counsel because of state or local court rules or at the discretion of individual judges.

“The report chronicles the slow, but persistent, progress of state court efforts to increase transparency in jury selection procedures and accountability for compliance with state and federal requirements for representative jury pools,” says Paula Hannaford-Agor, director of the National Center for State Courts’ Center for Jury Studies.

To be effective, collecting race and ethnicity information must begin with the initial jury summons, according to the report. When a potential juror responds to the summons questionnaire, they should be asked to identify their race and ethnicity, along with other demographic data. Later when they show up at the courthouse, that information is already part of their record.

In most states, this should not be an overly burdensome fix, Semel says: “It requires reconfiguring online jury systems, but in most states those online systems already exist. It is a matter of adding questions to an existing system.”

The report proposes that each prospective juror’s self-identified race and ethnicity be available to the trial court and counsel before jury selection. It also explains that absent this information, lawyers and judges often rely — consciously or unconsciously — on stereotypes both to identify jurors’ race and ethnicity and as a reason to strike them. In addition, the report also recommends that each judicial district’s race and ethnicity data be published annually by the courts and available to anyone investigating jury composition or selection.

Hannaford-Agor notes that implementing the report’s recommendations would enable courts to more reliably assess whether their jury pools are representative of the racial and ethnic demographics of the communities from which they are drawn.

“Semel’s study will encourage more state court leaders to implement data collection procedures that will help them determine whether reform efforts are having their intended effect and, if not, help identify additional steps,” she says. “Once state court leaders recognize that the risk of fair cross-section challenges does not increase — and in fact decreases — by providing accurate information on which to assess representation in the jury pool, I sincerely hope that they will look to the study for examples of statutes, court rules, and administrative orders to consider enacting in their own jurisdictions.”

Rooted in the clinic

Now all law school graduates, Jang, Slaton and Ramirez continue to use the skills they honed in the clinic.

Slaton, a first-year associate at Perkins Coie in San Francisco who’s already handling a pro bono death penalty case, says her work on the report provided a crash course in intense cold calling of government agencies, scanning state laws, and “how to be best friends with your librarians and what a truly incredible resource they are.”

Jang, a deputy public defender in Orange County, says she is using a template motion that she worked on with Semel to request juror demographic information in court.

All three hope their work benefits future defendants nationwide.

“I hope people take from the report the importance of collecting this race and ethnicity data from prospective jurors, both to ensure our jury system is functioning properly and to ensure that criminal defendants are judged by juries that actually reflect the demographics of their region,” says Ramirez, a deputy public defender in Contra Costa County.

Semel agrees and sees the clinic’s latest report as another crucial step in ongoing efforts to ensure that juries are representative.

“The premise of the report and our recommendations is that race permeates jury selection as much as it permeates every aspect of the criminal legal system.” Semel says. “We cannot be blind to the ways in which racial discrimination — whether explicit or implicit — continues to whitewash jury boxes. Structural reform starts by squarely facing how systems function rather than pretending they function as we wish they did.”