By Kirsten Mickelwait

As the Elizabeth Josselyn Boalt Professor of Law Emerita, Kristin Luker has received more than her share of accolades: Fellowships from Ford, Guggenheim, and the Endowment for the Humanities. A Pulitzer Prize nomination. Recognition as one of the most influential sociologists in the nation. An invitation in 1993 to meet with President Clinton to discuss some of the country’s most pressing issues and, the following year, a White House request for her testimony on teenage pregnancy.

But ask her about her proudest professional achievement, and she mentions none of the above.

“I’d have to say I’m proudest of my work with the research center,” Luker said, referring to the multi-disciplinary Center on Reproductive Rights and Justice (CRRJ) she founded at Berkeley Law. “It’s allowed us to think about the bigger picture around reproductive issues and breaks down the siloes of jurisprudence and social policy—people in these areas of expertise often just don’t talk to each other.”

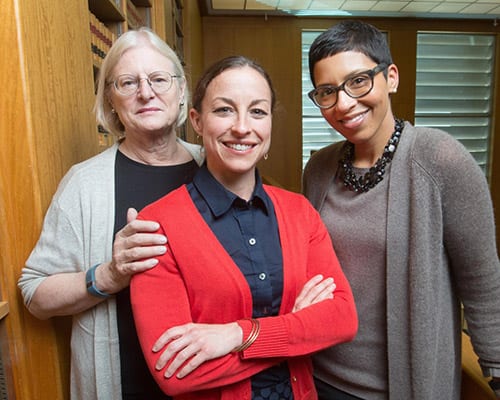

On April 1, Professor Luker was honored at a conference celebrating her research and scholarship. See photos of the event here.

The CRRJ is one of the first centers of its kind at an American university, cross-fertilizing the research and expertise of lawyers with demographers, community activists, social scientists, theologians, and historians, among others. In this think-tank environment, academics and activists can look at such issues as abortion, birth control, and ethical sex from a broader, holistic context and analyze the numbers behind the headlines—and flawed public policies.

“By founding a reproductive rights think-tank at the nation’s top public research institution, Krista has helped to legitimize the academic credibility of this field of study and to foster new thought leaders in this area of practice,” said CRRJ Executive Director Jill E. Adams ‘06.

The idea for the center came to Luker while she was on sabbatical in 2010. “I was sitting in front of my computer and found myself wondering, if I could do anything, what I would do?” she remembered. “Reproductive rights and justice affect our entire population across a broad range of issues over our life spans—decisions if and when to have children, access to education, raising our families in non-polluted environments, incarceration, welfare, the whole gamut.”

Since then, the CRRJ has influenced discourse and strengthened law and policy efforts by bridging the gap between academics and advocates. “At a time when most scholars would be resting on their laurels, Krista was thinking about how to move several different conversations forward in a productive way,” said Berkeley Law Dean Melissa Murray. “CRRJ’s amazing work in the short period in which it has existed is a powerful testament to her vision.”

A fertile realization

Another epiphany occurred 35 years earlier, when Luker first realized that she wanted to focus her career on women’s issues. She remembered sitting in a classroom as a sociology doctoral student at Yale in the mid-seventies. “I suddenly understood that a woman’s entire future could hang on the head of one tiny little sperm,” she said, laughing. “It’s a principle of social organization: By regulating fertility, you regulate women.”

Luker eventually ended up back at Berkeley, where she’d studied as an undergrad and where she has taught for nearly 30 years at both Berkeley Law and in the Sociology Department. She authored several books, including Taking Chances: Abortion and the Decision Not to Contracept (1975); Abortion and the Politics of Motherhood (1984; which received the Cooley Award and was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize); Dubious Conceptions (1996; selected as a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”); When Sex Goes to School: Warring Views on Sex – and Sex Education – Since the Sixties (2006); and Salsa Dancing in the Social Sciences (2008). She’s currently at work on her seventh book, a political history of sex from 1873—the date of the Comstock Act, which criminalized abortion and contraception—to the present.

Since those first heady years of feminism, Luker has seen the landscape of women’s rights lurch forward and back over the decades. “My students think that there used to be discrimination against women, and then it went away,” she said. “But if you want to see the face of gender discrimination, just look at the Supreme Court. Ruth Bader Ginsberg’s husband was, by all accounts, a saint. But both Sotomayor and Kagan are both single and childless. Being told we have to choose between a family and a career to be truly successful is another way of discriminating against women.”

Not just the answer, but the problem itself

Such lingering inequality underscores the importance of women studying law to become attorneys and law-makers. “I’m a big fan, not just of demographic diversity, but intellectual diversity,” Luker said. “Women bring a lens that shines a new perspective on old issues.”

Because there was no existing casebook on the subject, she co-authored with Murray the first law-school textbook on reproductive rights and justice. “If there’s no casebook, that’s a great disincentive to teach it,” she explains. “It gives the subject legitimacy. And there was a huge pent-up demand for it.”

“Krista’s legacy in the field of gender studies is unparalleled,” said Murray. “Her works on abortion and motherhood are required reading for anyone studying these issues.”

Looking back on four decades of work in gender equality and reproductive justice, what does Luker consider her greatest legacy? “I hope I’ve helped to create a generation of scholars and activists whose basic response to the status quo is ‘I don’t think so,’” she smiles. “I hope I’ve deepened our capacity to look not just for the answer to a problem, but to see if we’ve accurately framed and defined the problem itself.”

Done and done, Adams said. “Krista has definitely shaped the thinking and inspired the actions of legions of feminist scholars, researchers, and advocates across generations.”

And for those who still think that gender issues and reproductive rights only affect, at most, half the population, Luker has cautionary words. “As long as there are people whose lives are being limited by the world around them,” she said, “your own chances are also at risk. You’re only as safe as our most vulnerable population.”

Professor Luker was honored at a conference celebrating her research and scholarship on April 1. See photos of the event here.