By Susan Gluss

The Carnegie Corporation has chosen Katerina Linos as one of its 2017 research fellows, a well-earned honor for this extraordinary scholar. Announced last month, the prestigious fellowship, nicknamed “the brainy awards,” provides up to $200,000 for social science and humanities research—the most generous stipend of its kind. Professor Linos has also received support from the Center for Technology Research (CITRIS), among other funders, and is involved with the Berkeley Interdisciplinary Migration Initiative (BIMI).

Linos, a co-faculty director of the Miller Institute for Global Challenges and the Law, is studying an urgent global challenge: the European refugee crisis. She’s concentrating her studies in Greece, the first (and likely ultimate) reception country for many Syrian, Afghani and other refugees and migrants.

Linos is working with Ph.D. students Melissa Carlson and Laura Jakli and actively recruiting law students. The teams will examine how misinformation and rumors are created and propagated; how they impede refugees’ ability to claim basic human rights guaranteed by international law; and how new technologies can be used to close the communications gap.

The researchers will use social media data, ethnography and NGO databases to better understand the refugee crisis. They will also conduct experimental interventions to see whether and how misinformation can be corrected.

The following Q&A is an edited interview with Linos, shortened for the web. Here, Linos talks about her personal reasons for delving into the plight of refugees, and why we must protect the rights of the world’s migrant communities.

Susan Gluss: You must be thrilled about the Carnegie Award.

Katarina Linos: It’s very exciting. It will allow me to do work that is ambitious beyond what I even imagined possible.

I’ll do field work in Greece and pull together a multi-disciplinary team that can speak many languages. This includes students who will collect, translate and analyze material and then synthesize it so it’s understandable and useful.

SG: As a native speaker, your Greek will serve you well. What other languages are in demand?

Linos: Greece has migration from Syria and Iraq, so Arabic is very useful. But we also have migrants and refugees from Afghanistan and Pakistan, and they feel doubly underserved. Fewer people speak Pashto or Dari.

SG: How does this migration wave differ from past ones?

Linos: One really big change is this prevalence of communication technology that makes possible risky journeys across land and water. Migrants and refugees rely heavily on phones and smartphones, Facebook and WhatsApp. The classic refugee regime is built around the need for shelter and food. But what refugees also want is Wi-Fi.

SG: What compelled you to study refugees?

Linos: Large migration waves are a long-standing interest. Also, my grandfather was a refugee, so it’s a family story. Back in the 1920’s, there were forced population exchanges between Turkey and Greece –the same journey from Asia Minor to Greece today.

SG: Were circumstances similar then?

Linos: No. The idea of nationalism—of ethnically homogenous states—had emerged as the Ottoman Empire was breaking up and again after World War II. My grandfather went from Izmir in Turkey to Piraeus, a harbor next to Athens. At the time, the refugees migrating to Greece were ethnically Greek, with fewer language and cultural barriers. Still, any big migration raises questions about how to integrate all these newcomers. So, even when the research is not going well, a personal interest helps sustain me.

SG: You conducted ethnographic research last summer in Greece. What was a key finding?

Linos: The central finding was that miscommunication and rumors turn ordinary bureaucratic snafus into true crises, preventing refugees from exercising their rights.

SG: Why the focus on rumors?

Linos: Rumors matter. They can help make a bad situation a lot worse. They can completely destroy trust, not only in government but also in trusted NGOs and bodies like UNHCR (UN refugee agency).

Governments and NGOs can create rumors intentionally—but also unintentionally. For example, a policy may need updating to address a new crisis, but if it’s changing every two months there’s no way to communicate that effectively.

SG: What related issues are you grappling with?

Linos: We’re trying to understand how to correct misinformation. How do you build trust? Are refugees looking for something on paper with an official government stamp? Or are they looking for a statement repeated to them by many co-ethnics? Are they more distrustful of government information given their experiences of persecution in the hands of a government?

We’re also thinking about the native population. How do you build a positive story about migrants and refugees? Is it a narrative of family re-unification, a popular one in the U.S.? Or is it about a family’s fundamental right to send their kids to Greek schools, while trying their best to integrate? Or is it that they really want to move onto Germany and will leave the moment they’re able to?

SG: Is your goal to help refugees, or to help governments work with them more effectively?

Linos: Both. And it’s not just Greece. Unfortunately, we’re seeing a rise of xenophobia and the far-right. Certainly, on a European level, but in other parts of the world, as well. These questions of miscommunication and distrust are even more pervasive in developing countries, which now host the bulk of the world’s refugees.

SG: How will your research methods differ from past work?

Linos: We hope to study rumors in a more systematic way. We can do this because of technology and because of how NGOs on the ground are already collecting some of this data.

Forty to 60 Facebook pages focus on communications among migrants and refugees. There’s a particularly good NGO called Internews whose News That Moves project collects and debunks rumors online. Because there are multiple players, public websites and refugees’ internet posts, I believe that we can combine traditional methodologies with larger scale communications. It would be impossible for us to go and talk to people in 12 countries, but following that trail on the internet might be more feasible.

SG: I didn’t realize how reliant refugees were on technology.

Linos: It’s become essential. Mapping is one very important tool, for example. The other is simply communicating with people along the journey and with people back home. Some of the messaging apps end up being very cost effective, and that was the advantage of WhatsApp initially.

SG: Doesn’t the Greek government have an official website with information for refugees?

Linos: There are several websites with general information in English and sometimes Arabic. But it’s very hard to follow the asylum application process online. Part of our analysis focuses on problems caused by governmental changes just to the preregistration section.

SG: What sorts of changes?

Linos: Initially, people were supposed to preregister and then show up at government offices for interviews. That didn’t work. The government said, “Let’s do it over Skype.” That didn’t work either. People could get onto Skype, but the government allocated only one employee plus translators to field thousands of calls.

Then they sent caravans to camps to give out preregistration bracelets. But, that didn’t work because the government did not communicate properly—and migrants and refugees flooded the camps. So, it’s not straight-forward.

SG: You say one downside is that people turn to smugglers for information.

Linos: It’s almost a paradox: One goal of not communicating how long this process takes is to deter people from smugglers. But, in fact, people end up going to smugglers because they will give you some information when you ask for it.

Another downside is this deep distrust of government and aid organizations. Many refugees are not willing, for example, to give any identifying information to doctors—they’re scared that their data will be given to police.

Yet another consequence is a rise in ethnic tensions, especially when it’s really not transparent who’s getting scarce goods and who’s not.

SG: Who’s spreading the rumors and misinformation?

Linos: Everyone. Refugees need to make sense of the world in which they’re operating. So, they’ll hear bits of information from their neighbors that they might believe or not, but they’ll act on it just in case it’s true.

Smugglers will tell you the governmental process will require bribes. The governmental process will lead nowhere. They have an active interest in propagating misinformation to further their own business model.

SG: What advantages do smugglers have?

Linos: They’re available. They have undergone the same journey. They have language and ethnicity in their favor. And they’re basically willing to pick up their phones and make extraordinary promises. So, the government might in fact be offering benefits, but they don’t want to say to whom, or when and how. The smugglers have very strong incentives to promise more than they can deliver.

SG: What other research will you conduct this summer?

Linos: One goal is to study the integration of migrant and refugee children in schools.

I’ll also be working on aspects of xenophobia. The refugee children tend to be settled in poor places. So, how do people who are themselves disadvantaged react to the idea that suddenly a lot of children who don’t speak Greek will be sent to their elementary schools?

I’m thinking of anarchist groups clashing with the extreme right in a violent way. And parents concerned about issues of, “Are these kids vaccinated? Will they delay the learning process because of the language barrier?” So, one issue is how to reduce tensions that may emerge.

SG: It seems that just one rumor can incite incredible violence.

Linos: Well, there are ethnic tensions that shouldn’t be there. We’ve had camps burnt down on several islands on suspicion that “the other group is going to get prioritized, and we will be kicked out.” Rumors about when camps will close, or when borders will open are very, very, salient to refugees.

How you make out a story when there’s very limited amount of information is just difficult. It can go in many ways.

SG: You say access to information is more critical than food and shelter. Why?

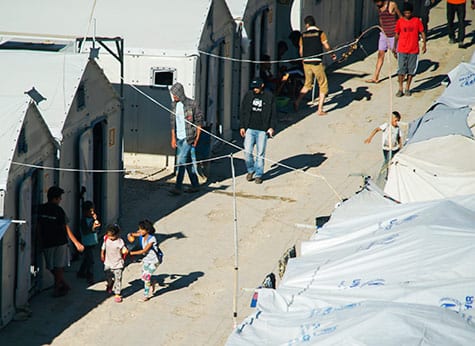

Linos: Food and shelter needs are easier to meet. Food is not of high quality, but there’s food. The need for shelter is met in a reasonably bad way. The best camps have small structures; other camps have tents.

But once you’re in an uncomfortable tent eating bad food, the real worry is, “Is this my new life? When can I move on?” That need for information really gets some people anxious. Migrants and refugees want to believe this is transitory. The question, “How do I get to the next step?” keeps people up at night.

SG: On average, how long are refugees in the camps?

Linos: The really distressing statistic is that, many refugees stay for decades, often for the rest of their lives. More than 40% of the refugees cared for by UNHCR are in protracted refugee situations. So, the idea that refugees are transitory and will soon get resettled to a new country where they can live a good life, or go back home, is a fiction in many cases.

In Greece, people have only been there for a year or two, but just how quickly the transition will happen is an open-ended question.

SG: Do you have recommendations about how to better communicate with refugees?

Linos: It seems clear that the current policy is not working. At a minimum, conveying information about steps and timelines is in huge demand. It’s hard to justify what I think is the dominant policy of the Greek government and of UNHCR to withhold information. The idea that people would be better off assessing risks in the absence of information seems misguided.