By Gwyneth K. Shaw

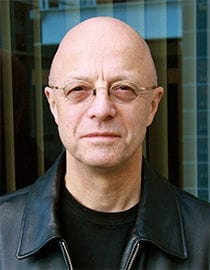

In his recently published book, In the Matter of Nat Turner: A Speculative History, Berkeley Law Professor Christopher Tomlins digs deeply into the persona of the Virginia slave Nat Turner and examines the legacy of the 1831 rebellion he led. Published earlier this year by Princeton University Press, the book is both a spiritual biography of Turner, a critical examination of his rebellion, and an analysis of the rebellion’s impact on antebellum Virginia, on the American South, and on the nation.

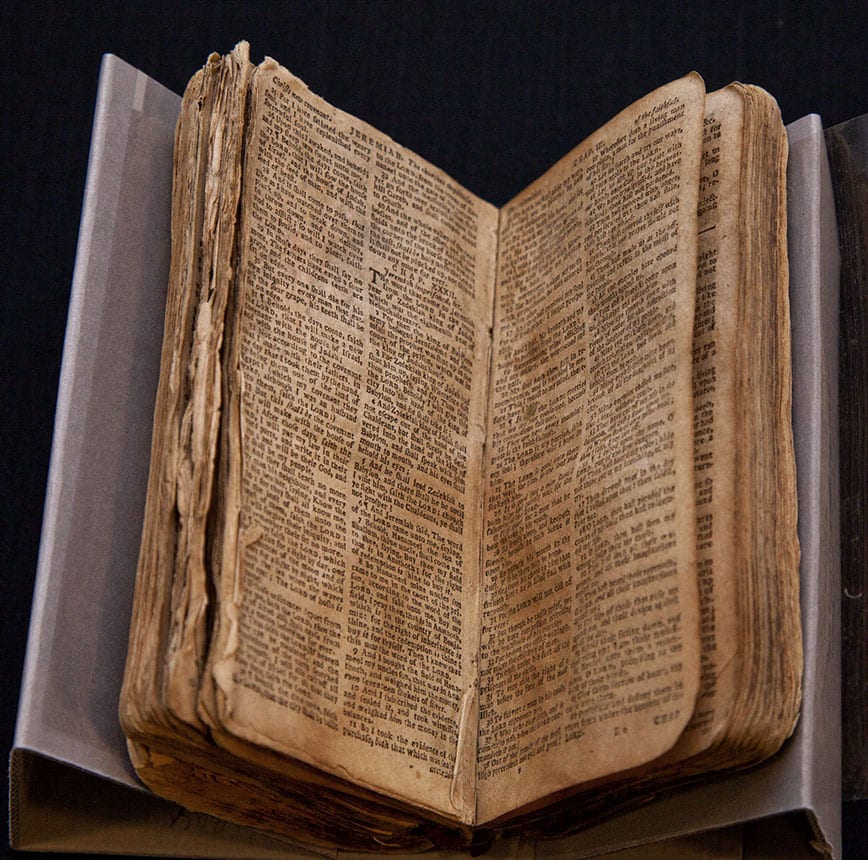

Tomlins also turns a diagnostic eye on The Confessions of Nat Turner — both Thomas Ruffin Gray’s hastily-compiled pamphlet issued a few days after Turner’s execution, and William Styron’s 1967 novel, which borrows its title and narrative outline from Gray’s pamphlet — and deconstructs the mythology around Turner to which both contributed.

Tomlins, who focuses on history and the law and has authored several other books, will talk about the book at a Berkeley Book Chat event September 30 at noon. He discusses his lengthy dive into Turner’s story below.

Q: This book is the culmination of years of work on Turner and his time. What led you to this topic?

Tomlins: I had been curious about Nat Turner for many years, since I first read Thomas Ruffin Gray’s pamphlet, “The Confessions of Nat Turner,” which was published a few days after Turner’s trial and execution. But I never wrote about him except once, 30 years ago, and even then only very indirectly. Then, when I was trying to recover from my last book, Freedom Bound, published in 2010 (I always go through a period of fear and anxiety after finishing a major project, when I believe I will never have another interesting thought) I cast around for something new to focus on, and eventually I decided that it was time to scratch the itch. Freedom Bound was a big ambitious scholarly book that addressed close to a half millennium of Anglo-American history. Writing it was a huge task that often seemed endless. I told myself that a book about Nat Turner would be much more precise, more focused. It would be the history of a discrete personage and a discrete event.

Instead I soon found myself writing about God! But in fact what attracted me was precisely the mixture of violence and messianic religious fervor that the name “Nat Turner” represents. In the way that I think about history I am deeply influenced by the German-Jewish literary critic and philosopher of history, Walter Benjamin. To someone with Benjaminian sympathies, Turner’s apocalyptic Christianity and the violence to which it eventually leads him is irresistible. And then, as the project matured, I realized that I could also use it to express how I thought myself about the creative act of writing history. So In the Matter of Nat Turner is not just a work of history, it is also a book about history — my attempt to expound my own philosophy of history.

Q: You call your book “a speculative history.” American school kids learn about Turner in history class, but how accurate is the typical portrayal?

Tomlins: Americans know of Nat Turner as a Virginia slave who in August 1831 led a violent insurrection that bears his name (The Turner Rebellion), portrayed as such most recently in Nate Parker’s movie, Birth of a Nation (2016). Beyond that, Turner seems to be a complete mystery, an enigma. The historian and Turner devoté Kenneth Greenberg describes him as “the most famous, least-known person in American history.”

Tomlins: Americans know of Nat Turner as a Virginia slave who in August 1831 led a violent insurrection that bears his name (The Turner Rebellion), portrayed as such most recently in Nate Parker’s movie, Birth of a Nation (2016). Beyond that, Turner seems to be a complete mystery, an enigma. The historian and Turner devoté Kenneth Greenberg describes him as “the most famous, least-known person in American history.”

I call my book “A Speculative History” because it tackles the mystery of Nat Turner by placing a premium on conjecture and imagination, on the scholar’s task of wondering about the connections between events and causes, origins and outcomes. As an intellect, a thinking person, Nat Turner is a mystery because he exists only in tiny fragments of text. So conjecture and imagination are essential if one is to have any hope of retrieving him from those fragments.

Speculation doesn’t mean that I am making things up: I treasure the scraps of empirical evidence on which my book relies, because they are the only way I can have access to this fascinating person. But history is a highly interactive discipline.

The questions I thought it crucial to ask about Turner could only be answered by inspecting those text fragments minutely and then interleaving them with other texts — theological, philosophical, sociological, anthropological, literary, legal — that could provide me with the imaginative means of understanding what was latent in the fragments. Throughout my research, I wanted to know, what did he believe? What did he think he was doing in engaging in what looks like a hopelessly quixotic act of murderous violence against impossible odds? What impact did he have?

If there is a “typical portrayal” of Turner it would probably be one that gives most attention to the rebellion and explains the rebellion as an act of resistance against the horrors and exploitations of enslavement. The available histories are primarily narrations of the rebellion itself. My book differs in placing a premium on trying to understand Turner. I try to reconstruct Turner’s intellect because I want readers to appreciate that in Nat Turner we encounter a complex and intelligent person who does not interact with the world he inhabits in a simple way.

Q: Your book closely examines the two Confessions of Nat Turner: Thomas Ruffin Gray’s pamphlet and William Styron’s 1967 novel. How have those works, both written by white men, shaped the popular view of Turner? How does your book challenge some of those views?

Tomlins: We have access to Turner as a thinking person because while a prisoner awaiting trial and execution he spent the better part of three days talking to Thomas Ruffin Gray, who was a local attorney and who published his account of their extended meeting as a pamphlet. William Styron used the same title for his fictionalized autobiography of Nat Turner, published in 1967.

In a long “prologue” to my own investigation I use Styron’s Confessions of Nat Turner as my point of entry precisely because the furious quarrel over Styron’s portrayal of Turner in his book that raged between African American intellectuals on one side, and Styron and sympathetic white historians on the other, poses very precisely the question about how one goes about representing the past that I wanted to address. I am critical of Styron and his defenders, but I take seriously his attempt to write what he called “a meditation on history.” His problem was he could never explain what he meant by that. Had he been able to do so I think his book would have been less divisive.

Styron relied on Gray’s pamphlet for his own impressions of who Turner was, and he read Gray’s pamphlet precisely in the way Gray designed it to be read, as the account of “a massacre of unarmed farm folk” conjured into being by a “dangerous religious lunatic” obsessed by “bloody visions.” (These are all Styron’s words.) Styron didn’t want to have anything to do with this Turner, and so he invented his own Turner inspired by “subtler motives” in order to enable the man to be “better understood.” Styron’s fictionalized imagining of Turner was entirely fanciful. This was what got him into trouble, and rightly so. Nevertheless, the book was a major commercial success, and one can see vestiges of its influence in Nate Parker’s movie.

I give a lot of attention to Gray’s pamphlet, because it is the only means to gain any insight into Turner as an intellect. But as historical evidence the pamphlet has to be used very carefully — if it contains Turner’s voice it comes to us filtered through the mind of his white amanuensis. So my initial objective in examining the pamphlet is to ascertain just how much one can rely on what that voice says.

I concentrate first on the pamphlet’s structure — how is this text assembled? It is a complex document with multiple components. By breaking it up into its constituent parts we can see how Gray builds a cage of controls around the text of Turner’s confession that urges the reader to read it in a particular way. This desire to control how the narrative is read suggests to me that the narrative itself is comparatively free of direct manipulation. I also argue that the narrative falls into two parts, and that the part that describes Turner’s life prior to the rebellion is composed more roughly or clumsily than the part that describes the rebellion itself. Gray was interested in Turner’s life, but he was much more invested in producing an “authentic” account of the rebellion, which he had studied closely independent of his conversation with Turner.

In my view the first part was written hastily from notes taken during the prison encounter, whereas the much more careful composition of the second part suggests it already existed in semi-finished form.

By going to these lengths in analyzing the structure of the pamphlet I believe I can show that, notwithstanding its compromised origins in the work of an impoverished white attorney, the substance of Turner’s narrative can indeed be relied on as his narrative, particularly his account of himself. In other words, all the work on the structure of the pamphlet is an absolutely essential preliminary to an exploration of its substance.

Q: What in the book do you think would most surprise a reader who is casually familiar with Turner and his story?

Tomlins: I want the reader to confront the sheer intensity of Turner’s religiosity, and to appreciate the coherence of his expression of faith, all of which is absolutely central to his account of himself in his interactions with Gray. Most readers of Gray’s pamphlet read Turner’s narrative as Gray designed it, a single linear account in which the life’s final bloody events appear as an outcome ordained virtually from infancy. I think this is a very basic mistake.

Turner’s account of himself describes a painful struggle for spiritual maturity and a search for his calling both of which become utterly central in his life long before he turns to any intimation of interracial violence. Turner’s account of himself in the pamphlet is of a life, as was Christ’s, of preparation: a precocious infant gifted with uncanny knowledge; an adult tested in the wilderness, come to grace and baptism, confronted in his maturity by an immense task given to him by God that nearly breaks him, on the outcome of which rides the salvation of all. Turner substantiates this account of himself through scriptural references, which I interleave with theological commentary to build an interpretation of their meaning.

Other readings tend to treat Turner’s scriptural references as if they were decoration — it’s as if the reader is telling us, “well, he’s a religious man, and religious people are always sprinkling biblical citations into their discourse.” In my view Turner’s pattern of biblical citation is not random illustration, it is far more systematic. In a way, the most exciting discovery to me was to realize that the sequence of spiritual experiences, visions, and revelations that Turner describes was wrapped in a coherent and sophisticated pattern of biblical citation that discloses a really sophisticated messianic theology. As his faith matures he moves from acceptance of God’s call to service, to Christian discipleship, to visions of the crucifixion and of Revelation’s promise of the second coming, and finally to his own transfiguration and his assumption of the burden of redemption. Turner, in my view, thought of himself as the redeemer returned.

The first part of the book concentrates on the analysis of Gray’s pamphlet and Turner’s religiosity. As the book proceeds it addresses the event of the rebellion in two ways that I think are original and that I hope are interesting. First, it considers the local legal response to the rebellion as the equivalent of the rebellion’s violence. Antebellum Virginia legality is a slaveholder legality that relies on legal institutions for the enforcement of slavery, and that perpetrates retributive violence on rebellious slaves. Law does not “mediate” slave relations, it affirms them, and in doing so it affirms itself as a slaveholder legality. In the case of Turner’s rebellion, law affirms slave relations by subjecting convicted rebels to the peculiarly violent public death of hanging from a tree branch, and, in Turner’s case, exemplary postmortem dissection. Just as I give close attention to the violence of the rebellion, so I give equal attention to the violence of legal retribution. In effect, just as the book treats religious faith on its own terms rather than as if it were a kind of “code” to be penetrated to reveal a hidden “real” meaning (for example, William Styron’s “subtler motives”), so the book tries to treat the rebellion also simply as itself, in its case as a blunt instrument hitting a lump of meat, simply a materiality. And to this lump of meat I counterpose a different lump of meat – the retributive juridical violence that followed, wielding its own blunt instrument, the mechanics of hanging, another materiality.

Second I consider the impact of the rebellion on Virginia’s politics. This is a complicated question (the longest chapter in the book) but essentially an attempt to institute gradual emancipation in the wake of the rebellion breaks down in chaotic political conflict, which leads eventually to the reaffirmation of slavery and its insulation from the possibility of legal and political intervention through restatement of its vital importance to the state couched in the calculus of political economy and the language of internal improvement. Here one sees the confirmation of Virginia’s investment in an entirely commodified slavery as the means to realize its deep commitment to commercial agrarian capitalism.

Finally, in an “epilogue” I ponder the set of connections that I believe one can discern in Turner and his rebellion – faith and violence, religion and capitalism, legality and political economy – in a return to the book’s attempt to offer an explicit philosophy of history. Here, “Turner and his story” become a crucial vehicle for exploration of questions about how and why one writes history.

Q: Turner’s rebellion has particular resonance now. What do you think we can learn from his story?

Tomlins: I began by observing that In the Matter of Nat Turner is not just a work of history, it is also a book that attempts to expound, by example, a philosophy of history. And I referred to the deep influence Walter Benjamin has had on me. Benjamin was deeply interested in the relationship between our past (“what-has-been”) and our “now.” It is hardly news to anyone that history is constructed in the present. The question is, how do we conceive of that process of construction.

“Articulating the past historically does not mean recognizing it ‘the way it really was’,” Benjamin wrote in early 1940, part of his Theses on the Concept of History. “It means appropriating a memory as it flashes up in a moment of danger.” To appropriate that memory in the vulnerable flash of its recognizability is to act to redeem and fulfill the past. Benjamin wrote those words in Paris, as Nazi Germany prepared its invasion of France. In September of that year he killed himself, a fugitive from the Gestapo, attempting to reach Portugal, blocked on the Spanish frontier. His was assuredly a moment of danger, but the philosophy his words embraced did not express simply the fragility of history but also the hope of fulfillment.

Nat Turner’s was also assuredly a moment of danger to which he responded as the attempted redeemer of a failed past. The what-has-been of Turner’s attempt has no direct lesson for us beyond its example of courage in the face of impossibility. Rather the relationship between his then and our now is one that speaks of our responsibility, at our moment of danger, to our past.