“Gayface” at the Academy Awards: Queer Representation without Queer People

Authors

- Russell K. Robinson

Walter Perry Johnson Professor of Law

Faculty Director, Center on Race, Sexuality & Culture, Berkeley Law - Anna-Grace Nwosu

J.D. candidate, 2022, Berkeley Law - Isabella Coelho

J.D. candidate, 2022, Berkeley LawClick here to download PDF

Click here to see the Op-ed

In recent years, there has been heightened attention to racial representation at the Academy Awards, beginning with April Reign’s #OscarsSoWhite campaign in 2015. In response, the Academy has invited new members who are disproportionately people of color. After the police killing of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and other unarmed African-Americans in 2020, media companies began pulling from streaming services episodes of old TV shows that featured White actors in blackface. This trend followed an uproar about “white-washing” when producers cast White actors such as Scarlett Johansson, Emma Stone, and Ed Skrein as Asian characters. Skrein ultimately declined the role, and Daniel Dae Kim, a Korean-American actor, was cast instead. This wave of scrutiny and eventual progress, however, has not extended to casting heterosexual actors as gay, lesbian, and bisexual characters, which remains standard practice in Hollywood.

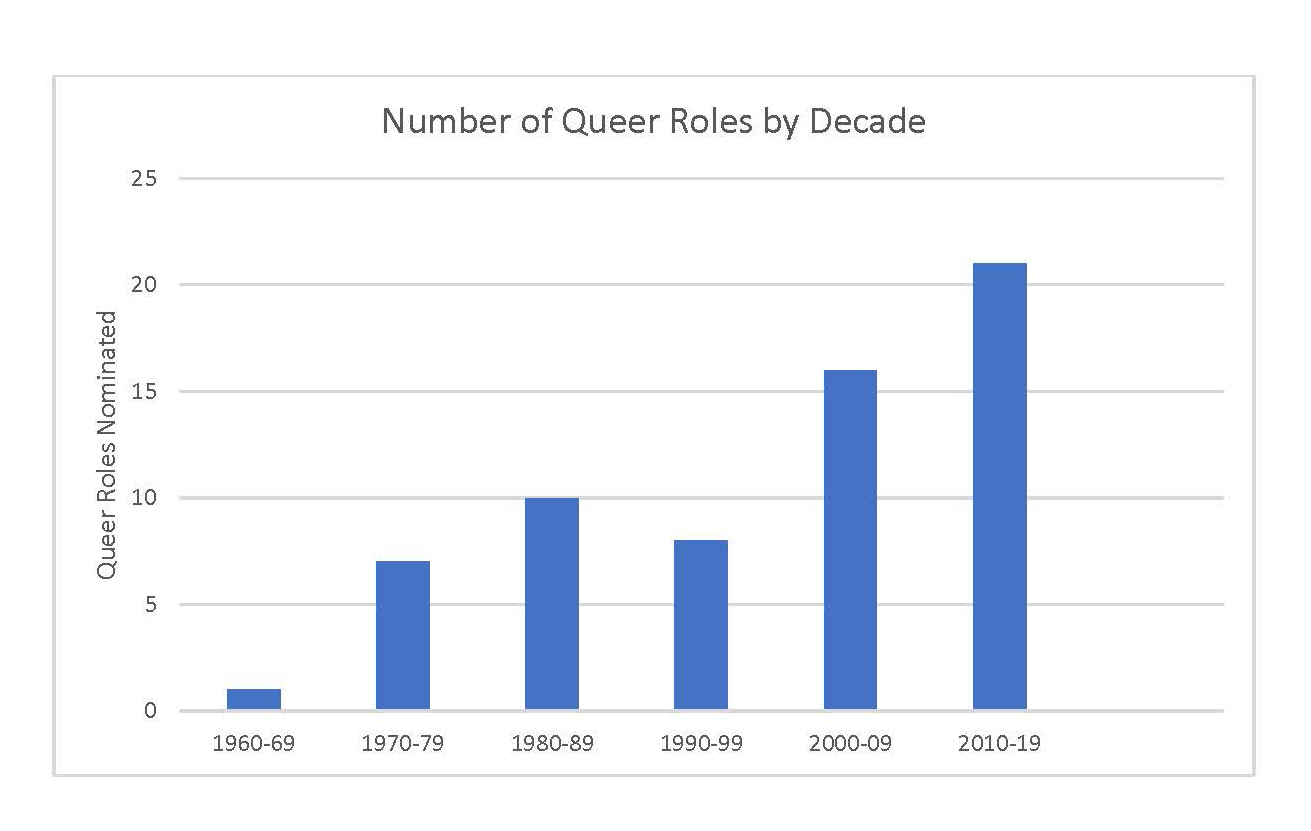

- This report identifies the Queer Representation Paradox. Recent decades have brought a surge in representation of LGBTQ characters in Academy Award nominated films. But LGBTQ-identified actors almost never play these roles. Nominee Colin Firth, a heterosexual actor nominated for playing a gay man, pointedly identified “Hollywood’s gay problem”: “If you’re known as a straight guy, playing a gay role, you get rewarded for that. If you’re a gay man and you want to play a straight role, you don’t get cast—and if a gay man wants to play a gay role now, you don’t get cast. I think it needs to be addressed and I feel complicit in the problem.” Some actors have resisted the idea that identity should limit their ability to inhabit any role. In 2018, Scarlet Johansson accepted the role of a transgender man, Dante “Tex” Gill, in Rub & Tug. Responding to the controversy around her casting, Johansson complained about “political correctness” in art and its restrictions. She stated that, “as an actor, I should be allowed to play any person, or any tree, or any animal because that is my job and the requirements of my job.” But as Firth’s comment indicates, the truth is that LGBTQ actors are not allowed to play any person. Indeed, they often generally cannot even play LGBTQ people. From 1960 to 2022, 5.4% of acting nominations have been for LGBTQ roles. In the 2000s, the share of nominated LGBTQ roles increased to 8%, and in the 2010s, it swelled to 10.5%. This expansion in representation correlated with a major shift in public attitudes in favor of LGBTQ equality, as well as the Supreme Court delivering landmark rulings in favor of LGBTQ rights. However, the 37 LGBTQ roles nominated during these two decades were portrayed entirely by actors who do not identify as LGBTQ.

- Failure to Cast LGBTQ-Identified Actors in LGBTQ Roles. An openly LGBTQ actor has never won an Academy Award for playing a LGBTQ person. Only two openly LGBTQ actors have been nominated for playing a LGBTQ person. Sir Ian McKellen is the only openly gay male actor who was nominated for playing a gay male character—in 1998’s Gods and Monsters. Jaye Davidson, who identifies as a gay man, was nominated for playing a transgender woman in The Crying Game. Not one of the eight nominated transgender roles was played by a transgender actor. Thus, although the Academy Awards is enhancing queer and trans visibility, LGBTQ-identified actors very rarely get to share in this rise. Meanwhile, actors who do not identify as queer build their careers by playing LGBTQ characters—sometimes repeatedly—to great acclaim. Consider two actors nominated this year. Each of Benedict Cumberbatch’s two Academy Award nominations (The Power of the Dog, The Imitation Game) arose from him playing a gay man. Two of Penélope Cruz’s three Academy Award nominations (Parallel Mothers, Vicky Cristina Barcelona) were for playing queer women.

- LGBTQ Actors Are Rarely Cast as Heterosexual Characters. Not only are LGBTQ actors shut out of playing LGBTQ characters in the most acclaimed movies, but they rarely receive nominations for playing heterosexual, cisgender characters. Less than 1 percent of nominees since 1960 were openly LGBTQ at the time of their nominations. By contrast, about 6% of the public identifies as LGBTQ.

- Lack of Racial Diversity: Queer visibility at the Academy Awards has historically consisted of White straight actors playing White queer people. Only 13% of nominated queer roles went to actors of color. None of the queer roles were played by an Asian or Asian-American actor. Ariana DeBose, as an openly queer, Afro-Latina woman, marks a rare departure from the Academy’s usual practice. This year, the Academy failed to nominate Tessa Thompson and Ruth Negga, who play Black multiracial women caught up in a tempestuous relationship in Passing. Thompson came out as bisexual in 2018.

- Bisexual Erasure: Recognition of bisexuality within Oscar media has also been inconsistent, especially for bisexual-identifying women. Angelina Jolie, who has been nominated twice and won once since coming out in 1997 on the cover of a lesbian magazine, has routinely been forgotten in articles on queer Oscar-nominated actors. For example, a Yahoo entertainmentarticle discussing this year’s nominations stated that Kristen Stewart (Spencer) and Ariana DeBose (West Side Story) were “the first openly LGBTQ performers nominated in the acting races since Ian McKellen in 2002.” Lady Gaga, nominated in 2019 for best actress, was also left out of that article. Vanity Fair and NBC News similarly overlooked Jolie and Gaga in their reporting. Though Gaga has identified as bisexual since the beginning of her career, she has had to defend the legitimacy of her queer identity on multiple occasions. Like many bisexual women, it seems that the actresses’ sexualities have been rendered invisible because they have publicly been involved with cisgender men, some of them famous. These erasures further diminish queer visibility.

- Tragic Endings: The quality of queer representation matters, in addition to quantity and the identities of the actors playing queer roles. A little over two-thirds (68%) of the endings for nominated lead roles featuring queer characters involved tragedy. Examples include a gay man dying mysteriously (A Single Man, Brokeback Mountain), the murder of a transman in a hate crime (Boys Don’t Cry), a gay man being jilted by his male lover, who marries a woman (Call Me by Your Name), and a lesbian serial killer being sentenced to death (Monster).

- Call to Action: This report calls for studios, producers, and casting directors to make affirmative efforts to cast LGBTQ actors as LGBTQ characters, and also to cast LGBTQ actors as heterosexual and cisgender characters. Actors have begun to express regret for being cast as LGBTQ characters and call for change. Recently, Eddie Redmayne admitted that playing Lili Elbe, a transgender woman, in The Danish Girl was a mistake and that he “wouldn’t take it on now.” Similarly, regarding her portrayal of Brandon Teena in Boys Don’t Cry, Hilary Swank admitted that she wouldn’t play a trans person today since “we now have a bunch of trans actors who would obviously be a lot more right for the role and have the opportunity to actually audition for the role.” Though not as common as the apologies for transgender portrayals, some straight actors have expressed similar regrets for playing gay characters. For instance, in 2020, Julianne Moore reflected on her role as a lesbian in 2010’s The Kids Are Alright. She admitted that when thinking about “this movie about a queer family, [in which] all of the principal actors were straight, I look back and go, ‘Ouch. Wow.’ I don’t know that we would do that today, I don’t know that we would be comfortable.”

- Making Change: Movie producers might follow the lead of recent advances in television. In 2018, openly gay producer Ryan Murphy cast transwomen of color as transwomen of color in Pose even though most of them had limited acting experience. The show was nominated for multiple Emmy Awards, and Michaela Jae Rodriguez became the first openly transgender woman nominated for Best Actress in a Drama. Further, although GLAAD, an LGBTQ advocacy organization, releases annual reports on queer representation, it does not appear to take into account whether heterosexual, cisgender actors played queer and trans characters. It also excludes from its reports transgender and queer actors when they play cisgender and heterosexual characters. Ultimately, queer and trans actors should have the freedom to be cast in a wide array of high-quality roles, just as heterosexual and cisgender historically have.

- Balancing Authentic Representation and Privacy: As important as representation is, the industry also should respect and protect each individual actor’s personal journey toward figuring out who they are and sharing that identity publicly. Some of the nominated queer roles, including Benedict Cumberbatch’s lead in The Power of the Dog, involve characters who experience same-sex attraction but do not publicly adopt identity labels. An actor who is living in that space might actually be a good fit for a role such as Cumberbatch’s. Cumberbatch has made comments vaguely raising the possibility that he may not be entirely heterosexual. But these concerns do not justify the almost complete exclusion of LGBTQ-identified actors from nominated LGBTQ roles. The Academy’s record of preferring heterosexual, cisgender actors for LGBTQ roles and rarely casting queer and trans actors as heterosexual falls short by any measure.

- Methodology: To identify queer roles nominated for Best Actor/Actress or Best Supporting Actor/Actress that were played by queer actors we applied the following methodology. First, we accessed the official registry of Oscars nominees from the Academy of Motion Picture Acts and Science’s website, which categorizes nominees from the first Academy Awards in 1929 to the present. Through the registry, we identified the nominees for Best Actor/Actress and Best Supporting Actor/Actress from 1960 through 2022. Next, we reviewed each nominated film’s IMDb page (Internet Movie Database). To determine whether the nominee’s character is queer or engaged in queer behavior, we accessed the film’s “Plot Synopsis” under the “Storyline” section of its IMDb page. If the synopses did not clearly identify queer activity but included vague descriptions of potentially queer behavior, we Google searched variations of “[actor’s name] [movie name] gay queer LGBTQ.” We sought resources that provided specific examples of queer activity in the film, rather than articles tangentially linking the character to queerness, for example, because they defended gay rights or because certain scenes could be characterized as queer.

After ascertaining a character’s sexual orientation/gender identity, we addressed the actor’s real-life sexual orientation/gender identity. For actors whose orientation/gender identity are not widely known, we Google searched variations of “[actor’s name] queer gay LGBTQ” to determine their sexuality/gender identity. If the actor was openly queer and/or trans, we searched for resources delineating when they self-disclosed their sexual orientation/gender identity to determine whether the actor was “out” when they were nominated for that Oscar. When a queer role was in the Best Actor or Best Actress category, we noted what happened to the character at the end of the film, sorting them into one of four categories. A positive ending was noted when the character’s position at the end of the film was better off than at the beginning, such as where a character was united with their queer lover. Negative endings were noted when the character’s position was worse than at the start of the film, such as when a character died (a frequent phenomenon). Correspondingly, neutral endings were noted where the character was no better or worse off than at the beginning of the film. Finally, we noted a toss-up where there was either both positive and negative aspects to the character’s fate or where there was not enough information in the synopsis to properly determine the outcome. Supporting roles were not included in our figures for tragic outcomes, as supporting characters’ outcomes were often too vague to reasonably ascertain.