By Gwyneth K. Shaw

As part of its broader commitment to considering and fostering diversity and inclusion within its storied stacks, the Berkeley Law Library staff have taken on one prominent example of bias: Reclassifying books, periodicals, and other materials that cover America’s Indigenous people to their own place on the shelves.

Library cataloger Kate Peck was inspired by a presentation at the American Association of Law Libraries’ annual meeting last summer. That talk, and the Berkeley project, stemmed from changes the Library of Congress made in 2014 to expand the classification system for Indigenous materials within the K class for law materials.

In 1969, the Library of Congress developed KF as the umbrella subclass for all American law topics — with just 28 call numbers for all works involving Indigenous law, echoing the exclusion and erasure of the people, tribal nations, and sovereignty issues in our society at large. (By comparison, Peck says, that same schema included 148 call numbers for federal income tax law and 90 for laws involving the U.S. Postal Service.)

Pushed to the bottom of the main category and squeezed into a tiny space, this treatment has been described by some in the cataloging community as “marginalization” and “ghettoization.”

After years of discussion and debate, the 2014 classification scheme enacted by the Library of Congress opened up a huge new space, literally and figuratively. “Law of Indigenous people in the Americas” now spreads from KIA to KIX, allowing for specificity at the continental, country, regional, and tribal level.

“This new system treats Indigenous laws as the valuable living systems that they are,” Peck says.

In the stacks

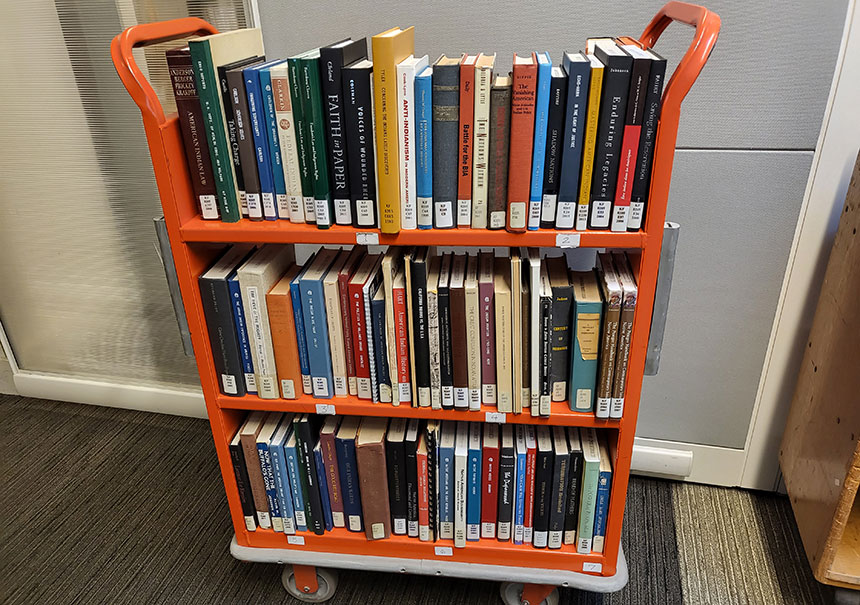

After the summer conference, Peck proposed reclassifying Berkeley Law’s Indigenous materials to the other catalogers: Irina Migal, Shelly McLaughlin, and Enedina Vera, as well as their supervisors. To get started, Peck dug through the law library’s digital catalog, then headed for the stacks — Lower Level 2, to be precise — to find the works that warranted review.

About 550 bibliographic records met her criteria, or about 860 physical items, since some items were multiple volumes. All but 20 of the titles were housed on 60 shelves in the stacks.

The library team has examined each title’s catalog entry, making sure they were complete and then discussing whether an item should stay in its existing classification or move into a new one. As with any reclassification project, there have been debates, and interesting questions that need answers.

“Classification is one of the main tools that libraries use to organize physical collections, and reflects our approach to knowledge management and organization,” Peck says. “Reclassifying our Indigenous law materials allows them to exist in their own context, acknowledging the sovereignty and independence of people who have been marginalized and isolated for too long.”

Marci Hoffman, who recently became the law library’s director, says the project’s importance made it an easy decision to set aside other work in its favor.

“Libraries are constantly changing to better address issues of diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging. We reclassify, or reorganize, materials for a variety of reasons — to make like materials easier to locate, to organize materials based on a more logical system, or to better address political, social, and economic realities in society,” she says.

She praised the staff involved, and added the library also tries to address diversity and inclusion issues through the materials selected for the collection, both print and electronic, as well as through the subject headings used in its catalog records.

“All of these actions are aimed at supporting our mission of creating and maintaining a welcoming and inclusive environment for those who use our library collections and services,” Hoffman says.

Pressing ahead

Another challenge is the Library of Congress’ list of subject headings, which help searchers find materials on the same topic. At a presentation about the reclassification project in November, Migal discussed some of the ways these headers have reflected intrinsic bias — including a long battle over the use of the term “illegal aliens” as a heading. That’s a place where Berkeley’s law librarians might push for change in the future.

There are further pockets of material that need review, which the catalogers noticed as they progressed, particularly involving Indigenous people elsewhere in the Americas and within individual states.

“My hope is that we will be able to continue expanding our on-shelf collection of Indigenous law materials, either through new acquisitions or by gathering materials that were classified elsewhere,” Peck says.

She lauded her library colleagues for their patience and engagement, and says the school’s Staff Circle Against Racism (which meets regularly) has pushed her to find ways she can make changes and improvements, even if there aren’t a lot of opportunities in her typical duties.

Peck says she thinks most law libraries are probably using the new classifications for material that have just been acquired, but doesn’t know how many have gone back and done the kind of review she and her colleagues did. She hopes to spread the word about this project through presentations and discussions within the law library community.

“Retrospective projects may be hard to justify fiscally, but I think most catalogers and librarians believe that it is important to improve on the systems that came before us, even if the day-to-day impact is small,” Peck says. “While treating Indigenous materials with the respect they deserve — and not just as an outpost of American history — will be a substantial undertaking, I think it’s something that will need to be done.”