By Andrew Cohen

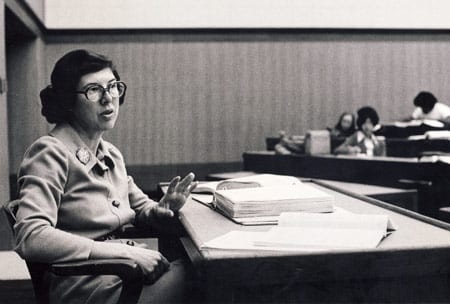

Berkeley Law Professor and former dean Herma Hill Kay, an iconic pioneer among women in the law, died in her sleep on Saturday, June 10. She was 82.

Kay, who taught at Berkeley Law for 57 years, wrote seminal works on sex-based discrimination, family law, conflict of laws, and diversity in legal education. A powerful advocate for equality in legal education and for women’s rights under the law, she also published numerous articles and book chapters on subjects including divorce, adoption, and reproductive rights.

In 1960, Kay became just the second woman to join the Berkeley Law faculty—hired when the first, Barbara Armstrong, announced plans to retire. During Kay’s tenure, the number of women students increased from a small handful to more than 50 percent of the class, and the number of women faculty grew exponentially.

She became the school’s first woman dean in 1992, serving for eight years. Despite facing severe budget restrictions and the 1996 passage of a California law barring public institutions from recruitment based on affirmative action, Berkeley Law thrived during her tenure with significant expansions to its curriculum, faculty, and clinical program.

“It’s almost inconceivable to think of our law school without Herma,” Professor Robert Merges said. “She filled every role we aspire to—mentor, teacher, scholar, leader—and did so not just well, but to the utmost. And in almost every role she was the first woman to dare to do it … and she did it all with grace, humor, tact, and a steady, quiet strength.”

Over more than five decades, Kay became a popular and nationally renowned professor of Family Law, Conflicts of Law, Sex-Based Discrimination, and California Marital Property Law. She also mentored numerous faculty members while promoting women’s advancement in legal education and the legal system as a whole.

Professor Emerita Eleanor Swift noted that Kay’s mentoring of women law students and junior faculty “opened the door to legal careers that simply did not exist before she and other women of her generation began to imagine them. The women law professors whom she mentored throughout her career constitute her enduring legacy to the law and to legal education.”

In a 2000 tribute article to Kay’s deanship, Georgetown Law Professor Emerita Wendy Webster Williams ’70 recalled how Kay invited all of Berkeley Law’s women law students to a meeting in the spring of 1969.

Leave a memory or a tribute to Herma Hill Kay here.

“There weren’t very many of us back then, so we fit into a small room that passed as the women’s lounge at the time,” Williams recounted. “She gently but firmly suggested that we should look to our interests (since men were unlikely to) and do something for ourselves as professional women. In a single stroke, she brought feminism home to us.

“As we worked with her suggestion over the summer and into the fall, establishing the Boalt Hall Women’s Association, developing a strategy for opening firms and clerkships previously closed to women, asserting our right to be where we were … I heard my calling. Herma provoked, inspired, encouraged, and brought into their own a whole generation of women law students.”

A new state of the (marital) union

A co-author of the California Family Law Act of 1969, Kay also served as a co-reporter on the state commission that drafted the nation’s first no-fault divorce statute. She later co-authored the Uniform Marriage and Divorce Act, which has become the standard for no-fault divorce nationwide.

“It was never undertaken to achieve equality between men and women,” Kay said during a 2008 interview. “It was undertaken to try to get the blackmail out of divorce and I think it has accomplished that…. Marriage is no longer the only career open to women.”

In 1974 she co-authored the seminal Sex-based Discrimination casebook, now in its seventh edition, with Professor Kenneth Davidson and U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

In 2015, Kay received the Ruth Bader Ginsburg Lifetime Achievement Award from the Association of American Law Schools (AALS)—from Ginsburg herself.

Reflecting on their first meeting in 1972 at a conference, Ginsburg told the AALS Annual Meeting News, “I liked her enormously … she’s a grand human in all respects.”

In a video tribute for Kay’s 2015 AALS Triennial Award for Lifetime Service to Legal Education and the Law, Ginsburg hailed “her persistent effort for well over a half century … to make what was once momentous no longer out of the ordinary—law faculties and student generations that reflect the full capacity, diversity, and talent of all of our nation’s people. Berkeley Law, legal education, and the legal world are beneficiaries of her selfless efforts.”

Kay’s other numerous honors include UC Berkeley’s Distinguished Teaching Award, the first Boalt Hall Alumni Association Faculty Lifetime Achievement Award, and the American Bar Association’s Margaret Brent Award to Women Lawyers of Distinction.

At a 2016 California Law Review symposium dedicated to Kay’s work, Interim Dean and fellow Family Law Professor Melissa Murray observed, “In the late 1960s and 1970s, as a revolution in substantive sex equality was sweeping California, Herma was at its center. She literally transformed the legal landscape of American family life.”

A determined path

Kay grew up in South Carolina, the only child of a minister father and a schoolteacher mother. In sixth grade, her civics teacher was so impressed by her sparkling performance in a classroom debate on the Civil War that she told her, “If you were my daughter, I’d send you to law school.” Kay’s mother, however, met that ebullient announcement with a withering reply: “No, you won’t go to law school. Girls can’t make a living as lawyers.”

Determined to disprove that notion, Kay enrolled at the University of Chicago Law School after receiving her undergraduate degree from Southern Methodist University in 1956. She earned her law degree in 1959 after serving as an editor on the law review and working as a research assistant for Brainerd Currie, with whom she co-authored two leading articles.

Kay served as a law clerk to California Supreme Court Justice Roger Traynor ’27, who hired her on Currie’s recommendation, then came to Berkeley to continue her meteoric rise.

“It is unusual to be a top scholar in two different fields,” said Berkeley Law Professor and fellow Family Law scholar Stephen Sugarman. “Herma was that rare academic who was a leading figure in at least three—family law, conflict of laws, and sex-based discrimination.”

In 1998, during her stint as dean, the National Law Journal named Kay one of the 50 most influential female lawyers in the country and one of the eight most influential lawyers in Northern California. Sugarman said “she brought us into the modern era” in several ways, “providing the key support needed to launch our clinical program” and shepherding vital improvements to the law school facility.

Working closely on the project with Swift, Kay launched the Center for Clinical Education, making Berkeley Law one of the first top law schools to provide students with valuable opportunities to gain hands-on training with clients.

“Now our clinical programs generally rank as being among the best in the country,” Kay said recently. “I’m very proud of that.”

Extending her reach

Kay held a wide range of leadership roles during her career. She was the president of AALS, a member of the Council of the American Law Institute, a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, a member of the American Philosophical Society, and the chair of UC Berkeley’s Academic Senate—among other positions.

She later served as an advisor for the American Law Institute’s Restatement of the Law (Third) Conflict of Laws project. At the time of her death, Kay was nearing completion of a book about U.S. female law professors in the 20th century—focusing on the 14 who began teaching before she did in 1960.

“From coast to coast, the legal academy and the profession are filled with young women and men who Herma has mentored, befriended, and guided over the years,” Murray said. “Some of these scholars were former students who, inspired by Herma’s example, went on to become first-rate legal scholars in their own right. Others are simply fellow travelers with whom Herma found common cause. In either case, her influence cannot be overstated.”

In her spare time, Kay was a pilot, avid swimmer, and accomplished gardener. Her husband, Dr. Carroll Brodsky, died in 2014. She is survived by three sons and four grandchildren.

Information about a memorial service is forthcoming.

“It is very difficult to think about our law school without Herma in it,” Swift said. “Her teaching and mentoring influenced generations of lawyers to set high goals for themselves, to work very hard, and to love the law. Herma was a model for these values. She will be greatly missed.”

—

Those wishing to make a gift online in memory of Herma can do so via the Boalt Hall Fund or the Herma Hill Kay Summer Fellowship Fund. If you prefer, you can also send a check, made out to either fund, to the Alumni Center.

To donate to one of the other established endowments named for Herma Hill Kay, please contact the Alumni Center at alumni@law.berkeley.edu for instructions, or send a check payable to “UC Regents” and noting “Herma Hill Kay Distinguished Professorship Fund” or “Herma Hill Kay Distinguished Professorship Program Fund.”

Mail checks to:

Alumni Center

UC Berkeley School of Law

224 Law Building

Berkeley, CA 94720-7200

Leave a memory or a tribute to Herma Hill Kay here.

Watch video tributes to Herma Hill Kay from Senator Dianne Feinstein and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.