By Andrew Cohen

Working tenaciously to level the playing field — in their own community and across the world — is a hallmark of Berkeley Law students.

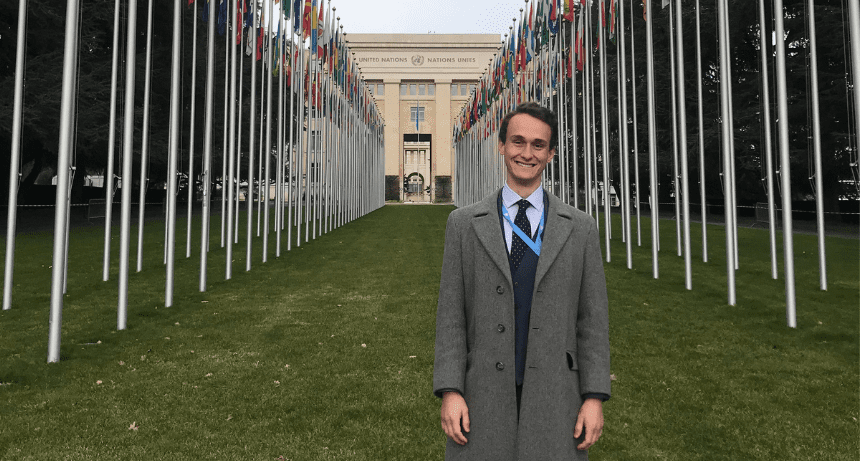

Cases in point: Allaa Mageid ’21, Ian Good ’22, Rachel Terrell-Perica ’21, and Marta Rocha ’21, each of whom is helping a different under-resourced nation assess United Nations Human Rights Council resolutions through field placements at the UNHR Program in Geneva.

“I was excited for the opportunity to assist as a student legal advisor,” Mageid says. “The UNHR Program presented a unique opportunity to practice the international law skills I’ve been cultivating throughout law school in a really practical way.”

Working vigilantly with Field Placement Program Director Susan Schechter and Coordinator Samayra Siddiqui to do their placement onsite despite the COVID-19 pandemic, Mageid, Good, and Terrell-Perica arrived in Geneva in January after Switzerland allowed their entry under long-term stay visas. For Rocha, a citizen of Poland, pandemic-related restrictions made it more feasible to work remotely there.

Berkeley Law’s student contingent is supporting the U.N. Missions of Afghanistan (Rocha), Sudan (Mageid), the Bahamas (Good), and the Marshall Islands (Terrell-Perica). They also take a weekly seminar taught by UNHR President Eric Richardson that teaches how to draft interventions, conduct legal research on U.N. documents, negotiate and comment on U.N. resolution texts, and other practical skills.

A former U.S. diplomat in Geneva, Richardson had three lawyers and the entire Office of the Legal Advisor back in Washington, D.C. at his disposal when he was deputy to the U.S. delegation to the U.N. Human Rights Council from 2013 to 2016. By contrast, various other countries often had little or no legal support at all — making it impossible for them to properly assess Council resolutions that form a vital basis of international standards.

“I felt like this made a mockery of the U.N.’s one country-one vote ideal,” Richardson says. “I wanted to help build the capacity of these countries, whose interest in human rights is no less than those of the larger developed states like the U.S., China, Russia, and the EU. That’s where our leveling the playing field initiative started.”

He launched the UNHR Program in 2018, and Berkeley Law joined the following year. There are 14 total students in the program this semester.

“I want to work at the intersection of technology, international law, and human rights law, so UNHR seemed like a great fit to explore my interests further,” Rocha says. “I’ve really enjoyed the fact that we get to attend all the meetings and see the inner workings of a large international organization.”

There are 98 Berkeley Law students now participating in the Field Placement Program (20 doing at least partially in-person work despite the pandemic), which enables students to spend a semester doing legal work for a nonprofit or government agency under a lawyer’s supervision. Schechter says it’s the highest semester total since her office began tracking such data in 2006.

Human rights momentum

Mageid was drawn to her UNHR placement by Sudan’s human rights progress since its 2018-19 revolution. In 2020 alone, she notes, Sudan criminalized female gential mutilation, abolished the death penalty for children, amended male guardianship laws, and discarded its apostasy law.

With only 12 diplomatic staff members, she is “continually impressed and inspired” by what Sudan’s delegation accomplishes. “They’re covering not only the U.N. Human Rights Council, but also engage in multilateral diplomacy efforts with the World Health Organization, International Labor Organization, World Trade Organization, civil society organizations, and more,” Mageid says.

Before law school, Terrell-Perica worked with a U.N. program in Papua New Guinea on a women-only bus system to reduce violence against women — but did not directly engage with the legal side of the U.N. Born in New Caledonia, she mostly grew up in Hawaii and calls her UNHR experience “incredible” thus far.

“It’s been impactful on my career considerations,” she says. “While I won’t immediately work with the U.N. following graduation, I hope to build upon my legal background and field placement experience to continue supporting human rights efforts in the Pacific Islands through pro bono work and other avenues.”

Good, who spent last summer in Mississippi working on death penalty criminal defense, has seen “lots of movement torwards the absolute prohibition of the death penalty” in the international community. Working with Bahamian Ambassador Keva Bain, one of five people in the elected body that runs the U.N. Human Rights Council, he has also worked on issues at the nexus of international human rights and climate change.

“I attended a meeting regarding an international push to create a Special Rapporteur on Climate Change and Human Rights, which is a fascinating and worthwhile idea,” Good says. “The Bahamas is committed to meeting its human rights obligations both at home and abroad. While no country is perfect, I’m thrilled to be working with a nation so determined to make this world a better place.”

For Berkeley Law’s UNHR students, helping a nation advance its human rights agenda while experiencing a semester abroad is doubly rewarding.

“I’m thrilled to be here in person with other Berkeley Law students,” Good says. “We’ve been able to meet in person outside and even went skiing recently with Eric. When you move to a foreign country, it’s so nice to see a familiar and friendly face.”

In related news, Joan Donoghue ’81 has been elected president of the International Court of Justice for a three-year term. Donoghue was appointed to the court, the U.N.’s main judicial arm, in 2010 and was reelected in 2015.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated that the students are all assisting small nations.