By Susan Gluss

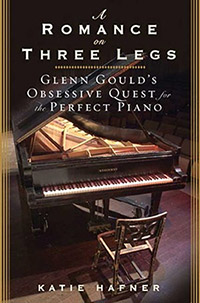

Journalist Katie Hafner’s book, A Romance on Three Legs, was a labor of love. The tale about the brilliant pianist Glenn Gould was “highly recommended … for those who enjoy an unusual tale well told,” one reviewer wrote. But fans seeking hard copies from the publisher were out of luck once the book went out of print.

Like many authors, Hafner was bound by a contract that gave exclusive rights to her publisher. She wasn’t allowed to print copies herself, as long as the eBooks were still selling. The book was “caught in a cage of copyright and contracts,” said Professor Molly Van Houweling at a recent faculty seminar.

But writers now have the power to challenge publishers with help from the Authors Alliance. The non-profit, co-founded by Van Houweling and Professor Pamela Samuelson, provides a voice—and legal tools—for authors eager to get their rights back. The alliance already boasts over 400 members since its official launch in May—including academics, biographers, historical fiction writers, and documentary filmmakers. Its advisory board includes two Nobel Laureates, a Poet Laureate of the United States, and three MacArthur Fellows.

“We want to demystify copyright law, demystify contracts, and empower writers so they can make their works more widely available,” said Samuelson, who co-directs the law school’s Berkeley Center for Law & Technology along with Van Houweling.

Writers “write to be read” Samuelson said, a motto that guides the alliance’s work. One such writer is Nobel Laureate Harold Varmus, who approached the group when he wanted to reproduce and distribute his memoir, The Art and Politics of Science. He consulted with Samuelson who helped him successfully negotiate with his publisher W.W. Norton the right to post a free version online.

Tools and tactics

The alliance is developing a legal arsenal to help authors like Varmus negotiate for better terms. One core element is a “digital agent,” a software program that will analyze and compare publishing contracts. The aim is to flag common terms that restrict authors’ rights and identify publishers that may offer more favorable deals. The alliance will publish annotated agreements online noting pitfalls authors should avoid, with the help of Berkeley Law Copyright Research Fellow Michael Wolfe and other collaborators.

“The idea is to praise publishers that offer attractive terms to authors and shame those who demand far more rights from authors than they need,” Samuelson said.

The nonprofit is also helping authors benefit from the little-known Termination of Transfer section of U.S. Copyright Law. The statute permits rights to revert back to writers—but only if requested—and only during a five-year window about 35 years after a contract’s been signed.

To leverage this law, the alliance is developing a “rights reversion toolkit” for authors of older works—but is also tailoring it for writers published more recently.

“Why wait 35 years to do a rights reversion if the work is no longer commercially available?” Samuelson asked. “The publisher’s not making any money on it; the authors aren’t making any money on it, and it’s only housed in a few libraries. We want to make these works available sooner. That’s the bottom line.”

The kit will be prepared by students at the Samuelson Law, Technology & Public Policy Clinic and will include best practices, sample letters to publishers, model licenses, and more.

Legal skirmish

The Authors Alliance evolved partly from Samuelson’s frustration with the Authors Guild and its years of litigation against Google Book Search. The Guild seeks $3 billion in damages from Google for posting snippets of books online. Samuelson calls the Guild’s lawsuits “unwarranted” and accuses the group of “toxifying the waters” about the alliance’s work.

In the latest legal skirmish, Samuelson and Assistant Clinical Professor Jennifer Urban filed a friend-of-the-court brief with the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in July, on behalf of the alliance. The brief argues that Book Search offers tremendous value, especially for out-of-print titles, by creating new ways to research, find, and access books; and by building new audiences—and incomes—for authors and publishers. Oral arguments are expected this fall.

The court recently ruled against the Authors Guild—in favor of the Hathi Trust Digital Library—in a similar copyright infringement case, which could bode well for the alliance.

Intellectual legacy

Several faculty members embroiled in contract disputes tapped the alliance’s expertise at a July seminar. Professor Jonathan Simon, who’s writing an anthology about scholar Philip Selznick’s work, faces copyright obstacles. The publisher owns exclusive rights to Selznick’s material and warned that getting them back “would be too expensive.” Simon plans to seek the rights with guidance from the alliance, but said that “clearly, this could chill many projects.”

Ironically, authors often can’t revise their own work, Van Houweling said, for the same reason: they don’t own the copyright.

As the digital age rapidly transforms the world of publishing, writers of all stripes—academic and commercial—need to be acutely aware of contract terms. “Writers are often too eager to take whatever contract publishers send. They just grit their teeth and sign it,” Samuelson said.

Pricing is another issue. Founding alliance member, Lydia Loren, was appalled at the high price for her legal case book. When she found out that students were unable to pay the $200—they either shared the cost or didn’t read the material—she formed an alternative publishing company, Semaphore Press. Students can now buy digital versions of her case book online for $30 or less.

In Hafner’s case, partnering with the alliance has paid off. Her publisher has agreed to use print-on-demand technology to print books upon request. The offer not only extends the work’s commercial life, Samuelson said, but it also “preserves an intellectual legacy worth protecting.”