By Andrew Cohen

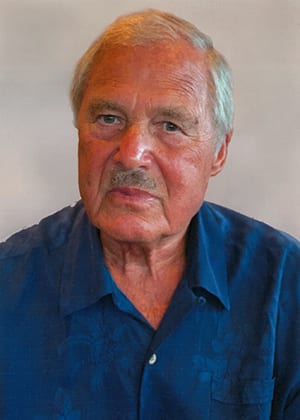

Each year, the Berkeley division of UC’s Academic Senate chooses two distinguished faculty members to give the prestigious Martin Meyerson Faculty Research Lecture. Berkeley Law Professor Franklin Zimring recently tackled a hot-button topic in delivering this year’s first lecture, “Police Killings: An American Tragedy.”

“Professor Zimring was considered to be the best in his field when came to Berkeley, and his stature has grown ever since,” UC Berkeley Chancellor Carol Christ said when introducing him during the March 29 online event. You can watch his presentation here.

A pioneering scholar in the study of violent crime for half a century, Zimring last year received the annual Stockholm Prize in Criminology, the field’s top international honor. His engaging Meyerson Lecture addressed why police kill far more citizens in the United States than in other developed countries.

“About 1,000 times a year in the U.S., civilians are shot and killed by local police,” said Zimring, who directs Berkeley Law’s criminal justice research program. “Most of these deaths are not necessary to preserve the life of the police officer or any innocent civilian.”

Zimring, who authored the acclaimed 2017 book When Police Kill, cited data showing that U.S. police kill anywhere from 5 to 30 times more civilians than police in five comparably developed nations. The glut of guns in the U.S., he noted, contributes to police anticipating the prospect of life-threatening violence, feeling anxious on their beats, and thus becoming more prone to use deadly force.

“You’re dealing with a society that has hundreds of millions of guns,” Zimring said. “Police have to carry guns because so many of the people they’re policing carry guns. If you could reduce the number of operable firearms that potential enemies of police are carrying, that would reduce the need for police to constantly think about their own use of defensive violence and to anticipate the potential of violent attack.”

Reform roadblocks

The only University of Chicago Law School graduate directly appointed to its faculty, Zimring joined Berkeley Law in 1985 and directed the school’s Earl Warren Legal Institute for 17 years. He has published major research on firearms and violence, juvenile crime and justice, deterrence, incapacitation, criminal sentencing, trends in crime, crime control, and police killings.

During his lecture, Zimring identified two main hurdles advocates face in trying to reform police behavior: oversight and incentive.

“If you ask who governs police in the U.S., the answer is that police have to govern police,” Zimring said. “Saving civilian lives should be a very important part of every police chief’s job. But police chiefs also want to support their officers and often find and assume that the shootings are fully justified.”

The vital task ahead, he explained, is how to motivate police administrators to protect civilians as much as they can — both from criminals and undisciplined police behavior.

“This is where money can talk,” Zimring said. “If courts award significant money damages from cases of wrongful death, municipal governments and police administrators will be motivated to avoid the fiscal pain. Most of the killings by police in the U.S. aren’t criminal, but they’re nonetheless regrettable and result in major social costs.”

Changing incentives

Zimring described possible remedies to control police violence when it goes beyond the boundaries that society deems permissible. They include money damages awarded to victims when killings and woundings take place, departmental discipline for wrongdoing, and training.

While violating police rules is “far less consequential damage than a criminal conviction,” Zimring asserted, stricter disciplinary policies for unnecessary use of deadly force would offer “plenty of incentive to encourage police to abide by the rules and regulations to control violence of police forces.”

Lamenting how the fear of encountering life-threatening violence clouds how police interact with citizens, Zimring said in reality most police conduct their careers without being regularly subjected to such a threat.

Nevertheless, he observed, presumed risks fuel a growing fear — and in turn the tendency to react earlier than necessary. “The potential for regrettable high violence is something that comes with the territory of urban policing,” he said.

Lauding Zimring’s seminal work on gun violence and police killings, Christ said, “Frank, in true Berkeley fashion, has not hesitated to speak his mind and has not shied away from advocating for new evidence-based policies and approaches to some of our most trenchant challenges. The quality of his work, the depth of his commitment to the truth, to reform, and to justice, embodies the very best that the university has to offer.”