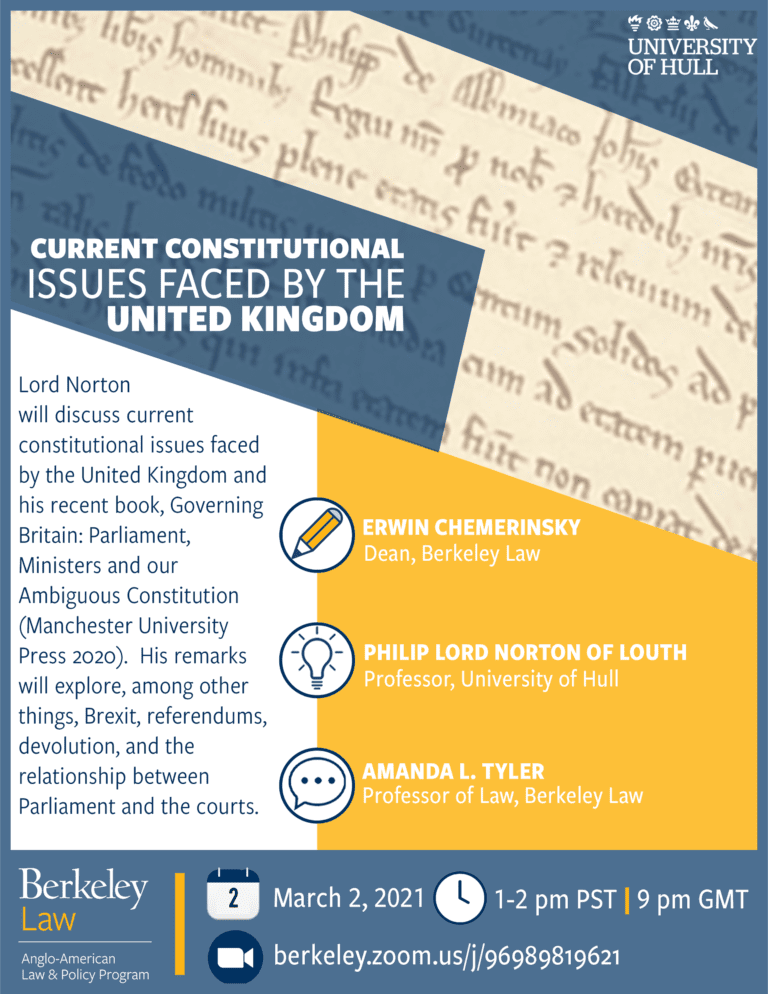

Current Constitutional Issues Faced by the United Kingdom

Tuesday, March 2, 2021 | 1 – 2:00 pm

Zoom | Berkeley Law

Event Video

Event Description

Professor Philip Lord Norton of Louth discusses current constitutional issues faced by the United Kingdom and his recent book, Governing Britain: Parliament, Ministers and our Ambiguous Constitution (Manchester University Press 2020). His remarks explore, among other things, Brexit, referendums, devolution, and the relationship between Parliament and the courts.

Panelists

Lord Norton of Louth (Philip Norton) is a renowned expert on Parliament and the British Constitution. He is the Professor of Government, and Director of the Centre for Legislative Studies, at the University of Hull, Professor of Government and Director of the Centre for Legislative Studies at the University of Hull, UK, and is a member of the UK House of Lords. He is the author or editor of 32 books, including The British Polity, now in its fifth edition and Politics UK, with Bill Jones, now in its eighth edition. He was elevated to the peerage in 1998.

Erwin Chemerinsky became the 13th Dean of Berkeley Law on July 1, 2017, when he joined the faculty as the Jesse H. Choper Distinguished Professor of Law. Prior to assuming this position, from 2008-2017, he was the founding Dean and Distinguished Professor of Law, and Raymond Pryke Professor of First Amendment Law, at University of California, Irvine School of Law, with a joint appointment in Political Science. Before that he was the Alston and Bird Professor of Law and Political Science at Duke University from 2004-2008, and from 1983-2004 was a professor at the University of Southern California Law School, including as the Sydney M. Irmas Professor of Public Interest Law, Legal Ethics, and Political Science. He also has taught at DePaul College of Law and UCLA Law School.

Amanda L. Tyler is the Shannon Cecil Turner Professor of Law at the University of California, Berkeley School of Law. Professor Tyler’s research and teaching interests include the Supreme Court, federal courts, constitutional law, legal history, civil procedure, and statutory interpretation. She is the co-author, with the Honorable Ruth Bader Ginsburg, of Justice, Justice Thou Shalt Pursue: A Life’s Work Fighting for a More Perfect Union, which the University of California Press will publish in early 2021.

Event Flyer

Transcript

Erwin Chemerinsky: Good afternoon my name is Erwin Chemerinsky and I have the great pleasure and honor of being the Dean of Berkeley Law and it’s my enormous pleasure this afternoon to welcome you to this important event of our Anglo-American Law and Policy Program. So pleased that is now part of Berkeley Law. And I’m thrilled this afternoon to be able to welcome Lord Norton to speak here at Berkeley Law as part of the program. To introduce Lord Norton to you I want to turn this over to my colleague Amanda Tyler. She’s the Shannon Cecil Turner Professor of Law at Berkeley Law, received an undergraduate degree from Stanford, the law degree from Harvard, clerked on the second circuit for Judge Guido Calabresi, and the United States Supreme Court for Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. She’s a prolific author. Her book “Habeas Corpus in Wartime” was award-winning and she has a new book out – just out – titled, “Justice, Justice Thou Shall Pursue: A Life’s Work Fighting For More Perfect Union,” that she wrote together with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Also I want to point out that Professor Tyler is the winner of the 2020 Rudder Award for outstanding teaching. Professor Tyler will introduce Lord Norton, he’ll speak, we’ll then have a chance for a conversation to Tyler, Lord Norton, and me, and then Lord Norton will be available to take questions. Amanda.

Amanda L. Tyler: Thank you Erwin for that very generous introduction. It is such a pleasure to welcome Lord Norton to our Berkeley Law community and to speak as part of the Anglo-American Law and Policy Program. I want to give a special thank you in my introduction of Lord Norton to Terry Long, a long time supporter of our program who introduced me to Lord Norton and helped arrange for his visit. I only regret that we could not welcome you in person to Berkeley, but hopefully we will be able to do so on some future occasion, Lord Norton. Lord Norton of Lao is the professor of government and director of the Center for Legislative Studies at the University of Hull. He is the author of or editor of some – wait for it – thirty-two books, just slightly prolific. Including “The British Polity”, which is I believe now in its fifth edition and “Politics UK” with Bill Jones, which is now I believe in its eighth edition. His most recent book about, which I hope we’ll hear some today, is “Governing Britain Parliament Ministers and Our Ambiguous Constitution,” published by Manchester University Press this past year. He was elevated to the peerage in 1998 with the title Baron Norton of Laos. He is an expert on the British Constitution and Parliament, among many other things, and he has served also among many other things as Chairperson of the House of Lords Constitution Committee. I can’t think of somebody better to talk with us today about current constitutional issues in the United Kingdom. Lord Norton thank you so much for joining us and the floor is yours.

Lord Norton: Right thank you very much and thank you very much for the introduction to speak to. In the time available I thought it may be helpful if I give a broad overview of where we are in terms of our constitutional arrangements and challenges. But in order to understand those, I need to give a brief constitutional history and I thought therefore I would just cover it briefly looking at it under the headings of constitution history and politics before leading into the specific issues that now faces. In looking at the constitution, the key point I think to make is that the United Kingdom is distinctive. We’re not quite unique but we’re certainly distinctive for having an uncodified constitution. Some people say the constitution we don’t have a constitution, some would say we’ve got a written an unwritten constitution. Both are incorrect. A constitution essentially is the combination of laws, customs, practices that determine the organs of the state, the relationship between those organs, and between those organs and the citizen. And so defined every nation has a constitution. The United Kingdom constitution is, in many respects, written because a large part of it is embodied in statute law. So it’s written it’s authoritative but what it is not is codified. So the principal elements, the tenets of the constitution are not drawn together in a codified constitution. So we can’t hold up a document and say this is “the constitution.” Although I would mention the point of course that even in nations that do have codified constitutions, the constitution is more than the document. It has to be interpreted. You have judicial decisions, you have conventions that develop, so the constitution extends beyond the document. But in the United Kingdom, our principal sources of the constitution are what elsewhere are secondary sources. So Statute Law and Common Law conventions and works of authority. So we are one of three nations that have an uncodified constitution. But that’s to discuss form. If we’re thinking about content, what are the essential tenants, well elsewhere I’ve identified a number, but for our purposes I just want to focus on what I think are the two crucial points for our purposes. One is that we are a unitary state. So power is concentrated at the center, there’s no sub-national level of government with constitutional autonomy. It is all the product of the center, it is created by statute, it can be abolished by statute. We are a unitary state. And related to that power resides at the center and it resides in one particular entity which is the crown in parliament. So the Doctrine of Parliamentary Sovereignty is the core component, it’s been described as the cornerstone of the British Constitution. In many respects it is the constitution. And the Doctrine of Parliamentary Sovereignty stipulates in the words of the 19th century constitutional lawyer Avey Dicey that the outputs of parliament – which means the queen and pond – are binding and can be set aside by no body other than parliament itself and no parliament combined its successor. So once parliament passes the law that is it. It cannot be struck down as unconstitutional and there is nobody to challenge. It it is the supreme authority. So power resides at the center and always has done. That brings me on to the history and you can trace the essential elements of the British constitution, I would say, back in millennium – certainly to the Coronation Oath of the 10th century – and our constitutional relations, our constitutional structure is essentially based on the relationship between the crown and parliament. So our constitutional history derives from that relationship. And essentially there are three key periods in our history that have shaped that relationship. The first was the emergence of parliament itself in the 13th century. There was no one point that parliament was created, it wasn’t a conscious formation. Essentially it developed from the king’s court. So the king already had a court comprising his leading baron and earls and the leading prelates the churchmen of the kingdom to give advice. But in the 1260s the decision was taken to invite knights – or summon knights of the shires – to the court and later burgesses from the towns essentially for the purpose of giving a cent to the king’s demands for taxation. So essentially on behalf of if like the nation the people there’s no sense of representativeness in terms of anything election or anything like that, but the leading figures in the shires and the towns will call to the court to ascend to the king’s demands. So the history of the relationship has been one of the crown making demands of parliament, parliament responding to those demands. So historically parliament has always been a reactive body, it does not determine public policy, it responds to the demands of the crown for taxation and for legislation for law. And that remains the case. But in the first two centuries of its existence it was able to use the leverage of the demands being made of it for requests made for ascent to use that to debate what the king was bringing forward and then to say, “Well before we give our scent we want you to redress our grievances.” So out of that became the functions that we associate with parliament in the United Kingdom: it scrutinizes law before approving, it it questions government it raises issues of concern to present to government, and in the early days as well it started to look at how the money was being spent so gradually the role of administrative oversight became important. Checking that the ministers of the crown, the crown servants were actually conducting themselves in an appropriate manner that money was being spent as it should. So it continued to be a reactive institution, but it developed the functions that have remained the core functions of the institutions since. Now the second historical key development was the Glorious Revolution of 1688-89. The 17th century was rather a troubled one for us – we had monarchs who were a bit overbearing and clashed with parliament that led to a Civil War in 1640s and a brief period of Republican rule, Republican government. Which was, I’m afraid, a complete disaster and so in 1660 we had the restoration – he was put back everything was put back to what it had been before the protectorate under Oliver Cromwell. And then there was a further clash under later King James II who as a result fled the country deemed by parliament to have abdicated who offered the throne to William of Orange and his wife Nary who was James’s daughter. But it was conditional on accepting the declaration of rights which was later enshrined in statute as the bill of rights of 1689. The key point for our purposes is that what that stipulated is that the king could not legislate without the ascent of parliament. So from the an institutional perspective of power – if not a pluralist one – parliament is a powerful body because unless you go through parliament, it’s not the law, it cannot be enforced. So the king could no longer get around parliament or or exist without parliament as he’d done before. He had to go through parliament. Parliaments to look to the king to determine public policy, but it was parliament that then had to approve what was laid before it. It could be not begot round. And that Glorious Revolution, the Bill of Rights are essentially the basic basics of our current constitution. So that was the constitutional framework, but then you factor in the politics which is the third historical development. Which is the 19th century the growth of mass membership political parties. So growing population, industrialization, a more specialized society. So a growth of a middle class artisans who were demanding a political voice. So what we saw were reform acts expanding the franchise to such an extent that voters could only be reached by some organized means. So what we saw was the emergence of mass membership political parties particularly after the 1867 Reform Act. So they came to dominate electoral politics, they raised the funds, they chose the candidates and so elections became contests between parties to gain a majority of seats in the House of Commons and for parties to deliver on promises they needed their members in the House of Commons to support those policies. So parties came not only to dominate electoral politics but parliamentary politics. So by the end of the 19th century, party cohesion in the House of Commons was a marked feature of politics. So what it meant was it confirmed a particular type of government – a parliamentary form of government. So government was chosen through elections to the House of Commons and it gave rise to a particular model: the Westminster Model. So we’re not the only form of parliamentary government it’s quite common elsewhere including in Europe and the Commonwealth, but the Westminster Model was distinctive from the Consensual Model you tend to find in Western Europe and that it was characterized by being executive dominated, two-party, and adversarial. It was government versus opposition. So not just Government with a capital “G” but Opposition with a capital “O.” It was structured, it was organized, and indeed publicly funded the leader of the opposition is a paid post. And the rules of the House of Commons are largely structured on two parties facing one another. But adversarial – so we have what Anthony King characterized as the opposition mode of executive legislative relations. So not an inter-party mode or an entrap party mode a non or a non-party mode or a cross-party mode, the opposition mode. So the two parties face one another, they do not seek accommodate accommodation but domination. They fight for the all-or-nothing response to electoral victory. The government has a majority, normally, therefore can get its program delivered but the opposition is entitled to be heard. So the chamber of the House of Commons becomes the grand debating arena of the nation. So it’s very much a chamber oriented legislature. So they fight it out – so both sides are heard they debate, but the government then gets its way because it has a majority. So that’s the Westminster Model and that was really confirmed by the politics of the 19th century and dominated Britain of the 20th century. And that Westminster Model was held up as a workable system one if anything to be praised and indeed exported. And supporters, who for most of the century dominantly was just generally accepted as a system of government now supporters, justified it on the grounds that what it delivered was responsible and accountable government. Because you had parties standing for election on particular programs – so the winning party was elected because of its program of public policy, it then had the opportunity to implement it and to stand before electors at the next election it was accountable. The electors could reward it keep in office or punish it, sweep it from office, put the opposition in its place. So therefore you knew who was responsible for public policy. So a factor of a unitary state there was just one body dominant because of parliamentary sovereignty, responsible for public policy. So responsibility wasn’t divided. You knew who was responsible for the output of public policy. And so that was seen as the benefits of the system and not really disputed. And that held for much of the 20th century. We now come on to more recent history when everything has started to change. So towards the end of the 20th century, the system started to come under pressure. We had economic problems, economic downturn – what was known as stagflation, rising in unemployment, inflation – we had the troubles in Northern Ireland so troops had to be sent in to try to maintain Lawton order, we actually had two general elections in one year, 1974 – neither of which produced a significant government majority, one only lasted a few months before you had the other. So critics started to be heard saying, “Well look our system’s not really working, we need change. Government is becoming too overbearing, it’s too centralized and it’s inefficient.” Lord Hailstrom in 1976 gave a famous lecture in which he coined the phrase “elective dictatorship.” So arguing that power was too centered and it wasn’t particularly efficient. So it wasn’t necessarily well governed, but we were centrally governed. And we started to hear demands for constitutional change – some people wanted a new electoral system, some wanted an entrenched Bill of Rights. And you also then started to hear different approaches to constitutional change. So intellectually coherent approaches that stipulated alternative constitutions to the one we had. In other words saying: this type of constitution would be preferable to the one we have. So there started to be an intellectual debate about our constitutional arrangements. Some reforming bodies were created to make the case for a new constitutional settlement. So you had that debate. You also had significant constitutional changes from well partly in the 1970s but especially from the end of the century through to the present day. They were significant and they were several. So the scale of change has been unknown really since the late 17th early 18th century. We’ve had significant constitutional change before but usually it’s been one particular event time to bed in before we’ve had another major constitutional change. What we’ve witnessed in recent years has been changes on a substantial scale all taking place roughly in the same era. So very so the scale is is unknown in in modern history a point well developed by a distinguished well actually former an American jurist and also a distinguished distinguished lawyer in this country. But anyway, the point is the scale of change. But before I come on to the specifics what the main changes were or have been there are two points to be made about them deriving from what I’ve just said and. First of all as I say there were lots of them but they were incoherent. By that I mean they’re essentially disparate and discreet. So each change was justified on its individual merits rather than deriving from a clear view of a type of constitution deemed most appropriate for United Kingdom. So if you like it was a response to particular problems. If you like bottom-up change rather than top-down deriving from a clear view of a particular constitution that we should be working towards. So as I say disparate and discreet, incoherent they did not derive from any of these intellectually coherent approaches to change that were being articulated. And the second point is the changes – the key changes that I’ve got to talk, about each in effect challenged the Westminster Model of government. So the model is under challenge but what flows from what I just said is the the changes haven’t been put in the context of a clear alternative to the Westminster Model. So that’s the – if you like – the key point to be made about it the context and you’ll see that from a discussion of the changes. So I’m just going to discuss the the major changes. I’m not going to try and be exhaustive because I’d overrun my time with all the if I run into all of them but there are key constitutional changes with major consequences. Now the first, which was the earliest and is now back with us, European integration our membership of the then European communities later became the European Union. So joining was the product of economic and political forces. We did not join the European communities for any constitutional reasons because it actually clashed with our constitution. Because in effect what was happening were policy competencies, policymaking capacity was being transferred from Westminster to a supranational entity in the European communities. So we provided that European Law once promulgated took effect in the United Kingdom of his regulations took a direct effect, directives could be implemented through UK law, but we could not challenge the principle. And it also introduced a new juridical dimension to our constitution because if there was a clash between European law and domestic law, European law took precedence and there were two very high profile cases in which provisions of UK law were struck down as being incompatible with European law. So that was a job to our system. It was we had difficulty accommodating it to our constitutional arrangement. So the parade of our membership, I think we’re constantly playing catch up in constitutional terms, was problematic. We have now withdrawn from the European Union and that’s proving consciously problematic because we’ve had an accumulation of nearly fifty years of European law which is not embodied in just one place. It’s sort of scattered around all over, so we’ve had the constitutional problems of actually achieving withdrawal which I’ll come on to because that’s created another problem, but then deciding what to do with that accumulated body of European law. The first task was identifying it, hanging on to it. So we have a now a new body of law which is known as re – and that this has a significant it’s a distinct form of law – retained European law. So we’ve now got that’s going to be a major challenge for government and parliament in deciding what to do with it in terms of what to keep, what to amend, and what to reject. So our membership of the European communities then the European Union been constitutionally problematic. But from 1997 onwards a whole string of changes devolution. So demands from different parts of the United Kingdom for a greater say. So implementing elected assemblies in Scotland Wales and then Northern Ireland and giving them certain powers. So technically– well they are created by statues so Westminster could abolish them all, politically that’s not really conceivable to achieve. And now key points are one is devolving power – so one is transferring some policy making competencies away from Westminster. So if you like with our membership the EU and then devolution. Some policy-making competence is moved upwards to the institution of the European community then the European Union, others if you like move downwards to the devolved legislatures. But it’s complicated in the context of the United Kingdom for two reasons: one is there’s no English devolutions, there’s no English parliament as such there’s a Scottish parliament, a national assembly Wales which is now Welsh parliament, and a Northern Ireland assembly. And the other key point is that one part of the United Kingdom completely dominates the rest. England has basically roughly eighty-five percent of the population, eighty-five percent of the wealth. So we’re in a uni basically you a fairly unique well it’s either unique or it’s not so I’d say it’s a unique situation because of that situation. So it’s not like a federal state where no one state is so large as to be bigger than all the rest put together. So it creates problems for determining the relationship. Westminster is dominant but its conferred powers in Scotland Wales and Northern Ireland. So the relationship is a problematic between Westminster and Scotland Wales and Northern Ireland and there are continuing tensions. And so there’s talk about we talk of a devolution settlemen. I point out that’s aspirational rather than descriptive – there is no settled state in the relationship between Westminster and the different parts of the United Kingdom. So we see particular tensions of the present time Scotland press forums allowed a referendum in 2014 on whether Scotland should become an independent nation it and the Scottish national party is again pressing for another referendum and to try to stave off independence Westminster has devolved more powers to particularly Scotland but it’s also devolved more to Wales now as well. So devolution is an issue – key issue for us is maintaining the union of keeping the parts of the union of the United Kingdom together. There are tensions within it. And now the second feature I want to mention is the use of referendums and as an aside referendum’s not referendum. And that previously unknown to the constitution from the 1970s on which we’ve used them particularly in different parts of the United Kingdom and racial devolution but we’ve had three United Kingdom-wide referendums and variously the promise of more referendums if certain policies are implemented. So they’ve become part of our constitutional architecture. The problem is that each referendum essentially is the product of political expediency. There is no clear agreement on when a constitution when a referendum should be held, it’s up to government to bring forward a bill for a referendum for parliament to approve it and essentially as I say it’s been the product of political expediency. But the point is that now referendums are there we can’t undo them so it’s the challenge of when do you hold referendums and fundamental to our system in the Westminster model that potential clash between if you like popular democracy through a referendum and parliamentary democracy or representative democracy channeled through parliament and that can create tensions and has done most notably in the parliament of 2017- 2019. So in 2016 we had a UK wide referendum on leave or remained within the European Union. There was a majority – might be a small one – but it was majority to leave to withdraw from the European Union so we had the outcome. It was then up to government to legislate to achieve the result – to withdraw from the European Union. Theresa May’s prime minister managed to get a general election in 2017 thinking she’d have a much larger majority. She didn’t. The government lost its majority. So no one party in that pond had a majority. So government was trying to get legislation through to enact its policy for withdrawing from the European Union but it couldn’t get a majority to do it. It wasn’t just the opposition opposing it as surge it was opposed by a transient majority in the house opposition, mps, some concert of mp some independent members are drawn from other parties that will manage to mobilize a majority to rest control of the parliamentary timetable from government and to try to impose policy on how we withdrew from the EU. Now resting control policy from the EU is completely contrary to the Westminster system of government and the basic relationship between the crown and parliament. So a very tense parliament where the government couldn’t achieve what it wanted and in which there was no majority for anything. There was a majority against what the government wanted and against whatever else was put forward the alternative proposals, but the key point for my purposes is the total lack of accountability. Electors cannot be held accountable for the outcome of a referendum and there was no one body to be held accountable for what was happening in the parliament of 2017-2019 because it was being determined by a transient majority. So there was no one body that would stand before the electors at the next election to be held accountable for what went on in that parliament. So that parliament was really problematic in constitutional terms for the Westminster system and for having an executive that could actually achieve outcomes. So a real tension there between the outcome of the referendum. So the very same people who voted in the referendum for one outcome then elected a parliament comprised of members who didn’t quite deliver on what the electors thought they were going to produce. So real tension there as a result of the introduction of referendums. So those are two key features that we’ve had. Another one I would identify is the new juridical dimension to our constitution which i suspect would be a particular interest to to Berkeley Law because there was no significant juridical dimension. A dimension really until the 60s and 70s because parliament was supreme, the courts were there to interpret the law to apply it, they could not challenge the output of parliament. As the late Lord Bingham – Tom Bingham – the great lawyer you know as he said: parliamentary sovereignty is imminent in our constitution, it can’t be challenged by the lawyers. It’s not a Common Law, constitution as some jurors have occasionally claimed. And so that was fundamental. So the courts didn’t have where they were there to perform a legal role but didn’t have political consequences. That changed from sixtes onwards – you’ve got a greater degree of judicial activism the court’s been more willing to question, challenge what ministers were doing not parliament. So judicial review became more significant but that wasn’t judicious in the American sense, it was judicial review to make sure ministers were actually or acting intraviries. In other words within the powers granted by parliament. But because of membership of the European Union that created a new juridical dimension because if there’s a clash between European and domestic law as a matter for the courts, devolution gave a new role for the courts because they became the constitutional courts for Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland because the default bodies could only act within what was granted by statute. So they got a new role there, but then they got a new role as a result of the Human Rights Act of 1998 incorporating the main provisions of the European convention on human rights into domestic law. I mean we long ago in 1951 we signed up to the European convention, so it was in international law but we only brought it into domestic law in the Human Rights Act. And this gave a new role to the courts – they can’t strike down measures of uh public authorities as unconstitutional, can’t strike them down, but they can issue declarations of incompatibility. So if it’s incompatible with the convention right they issue a declaration of incompatibility, it’s then up to parliament to change the law to bring it into line of what the courts have said should be. So formally parliament could not refuse to do that. In practice it’s acted in line with what the courts have said should happen to be compatible with convention rights. So courts have become much more active much more significant and facilitating that has been the creation of a supreme court. Our highest domestic court of appeal used to be the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords – so a committee of one house but it comprised lawlord. So our very senior judges who are appointed for the purpose of being law lords and forming that appellate committee. So highly respected, outstanding judicial body, but it was formerly a committee of a House of Parliament, the law lords were members of the house of lords they could speak in debate and so it decided that by the government that this was somehow inappropriate, that it should be a distinct body separate from parliament. So the Supreme Court was created and it was a physical entity, a change of location and name it was the same power – so the powers of the Appellate Committee sort of transferred to the Supreme Court. It was the same personnel it was the law lords moving out of the Paris Westminster across the road to a building the other side of parliament square. But there is the argument that that separation that physical move has had significant consequences making the court more distinct as an entity and emboldening the members of the court in the way they’ve done their job. So there’s an argument about the actual consequences of that move. So I just mentioned that because that’s also a matter of some debate and the courts have got much higher profiles recently for some of the cases that have been brought before them in different, on different issues particularly under Baroness Hale when she was president some very high profile cases raising issues about the relationship between the executive and the literature and between between – sorry between the executive and the courts – and between the ledger and the courts. I’ve elsewhere develop different um models to look at that relationship as to essentially when they’re friends foes or strangers to one another. But it’s created by that physical move has raised all sorts of questions about the relationship and how they fit with one another. So those are key features of our constitution and issues that are now very much on the agenda and as I say I’ve tried to identify the key major issues, I’ve not tried to be exhaustive. I could have gone on to House of Lords reform freedom of information all sorts of other issues and one of my favorites the fixed term parliaments act. So there’s an awful lot we could have I could have added but I just wanted to isolate what i see as a key issues that might resonate with you or that you feel are particularly pertinent to understand the tensions there are within our existing constitution. So there are pressures, it’s not clear where we’re going because they challenge the existing Westminster model without working towards some clear alternative. So a great many years ago – actually 1982, one of my books was called the Constitution in Flux – one of our leading lawyers at the time did a book review and said the title was prescient. I think he had a point. On that I will end because I want to allow time for conversation and questions.

Amanda L. Tyler: Thank you, Lord Norton. That was just exceptional and I certainly have a lot of things I’d love to talk with you about but I’m going to defer to Dean Chemerinsky to begin if he has something he would like to ask.

Dean Chemerinsky: Lord Norton, that was terrific. I learned so much from it. You covered an enormous amount in a short time and did so very clearly. I want to start where you began with the definition of a constitution. I teach constitutional law – in fact as recently as did so this morning – when I think of the constitution, I think of two characteristics that make it different from all other laws. One is the constitution is supreme over all their laws in the United States and the second the constitution is more difficult to change than all other laws in the United States. And yet as I listen to your definition of constitution and listen to you talk about it through the history of England, those two characteristics don’t seem present at all.

Lord Norton: I should give a good academic answer which is yes and no. On your first point yes, the constitution is supreme in the sense that, as I said, I think you can argue that the Doctrine of Parliamentary Sovereignty – the sovereignty of the queen in Poland – is the constitution in the United Kingdom. So that is the the the supremacy lay in the doctrine of a parliamentary sovereignty. So that is supreme. On your second point, I don’t think it I would not accept its axiomatic of a constitution for it necessarily to be entrenched. So typically maybe, as you have in the context United States so constitution will provide they cannot be amended other than by extraordinary means. But you could have the key provisions drawn up without it being entrenched. So I wouldn’t say it’s an intrinsic feature of a constitution. So I would say you can have constitutions – some are entrenched, others are not. So we have a discussion across here not about entrenchment of the constitution but whether we should have an entrenched Bill of Rights. So we have the Human Rights Act which is essentially a Bill of Rights in the terms it’d be understood, but it’s enacted as an act of parliament so parliamentary parliament could amend it. There’s no protection so there is an argument whether the provisions of that should be entrenched, but the key problem is parliament could then amend the law entrenching it. So you can’t have entrenchment under the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty. I mentioned the Fixed Term Parliament’s Act briefly and I’ll avoid giving a quite lengthy lecture on it, but and the Fixed Term Parliaments Act it provides that parliament– that House of Commons can vote for an early general election but it has to have a two-thirds majority of all mps to achieve that now. But that doesn’t entrench it because parliament can amend the act providing for the two-thirds majority and it can amend it by a simple majority and has done. So it got round the provisions the Fixed Term Parliament’s Act in 2019 by by passing another act by a simple majority saying there’ll be an election in December 2019. The Fixed Term Parliament’s Act notwithstanding. So our entrenchment is the supremacy but so my point is yes it is see it is supreme because it’s constitution because that stipulates the structure of the state, but you could have a constitution that formerly was not entrenched.

Dean Chemerinsky: I mean if I could ask just a quick follow-up question: if the constitution is not entrenched in the sense of making more difficult change and if the constitution’s principle is that parliament is sovereign, what makes the constitution different from other laws? And in the current context is there a difference between a declaration of incompatibility and a declaration that something’s unconstitutional?

Lord Norton: Yes because there’s no concept of being unconstitutional in our system because all people say, “Oh parliament did that it’s unconstitutional.” Well no, parliament did it therefore it’s constitutional. So I think that’s the key point, but you’re right because the supremacy I say is in the doctrine upon sovereignty so anything else could change by virtue of parliament providing that it changed. So one of the chapters in the book on Governing Britain addresses that point about the potential tension between the what have been dicey identified two key pillars of the constitution: parliamentary sovereignty and the rule of law. Now there are two problems with that. One is actually defining what we mean by the rule of law. That’s hardly specific to the United Kingdom. But the other is, of course, that parliament is the ultimate protector of the rule of law and could enact legislation constricting the rule of law and the courts would apply it. So we abide by the rule of law, but if you like it’s parliament exercising self-restraint in so doing because it there is no provision that is entrenched and the only imminent part of our constitution is that doctrine. So that so the constitution has ever existed as a over a millennium rests in power resides in the crown. All power resides there and that has continued to remain the case. And that’s what’s distinctive about the United Kingdom where we’re not unique in being uncodified, but we are distinct where we are then what sets us apart is that parliament – the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty has been as I say you can say that is the constitution.

Amanda L. Tyler: This is fascinating I think that if Erwin and I were to stay on we could follow up with a hundred more questions as students of our constitution. I will say just by way of commentary and then I want to ask you, unsurprisingly, more about the UK Supreme Court. It is interesting as someone who’s written a lot about the history of Habeas Corpus in both of our countries and thinks about these constitutional questions. There are scholars in the US who say our constitution is too hard to amend and so they champion courts sort of um doing it for us, if you will, and I can imagine drawing for example from the habeas context someone arguing that the British system might actually be better because it allows for so-called updating more easily. So there’s a just a wonderful dialogue we can continue to have on this question. On that note though – I did you talked about the Supreme Court – I’ve studied some of your court and I think they’re really at a real crossroads right now, as you say, with the withdrawal from the European Union and of course Johnson has been critical of the court. There have been suggestions of some small, some more dramatic reforms, one of the audience members is written in asking, for example, about whether the court ought to be maybe put back in the House of Lords as the law lords. I’m curious what you think the greatest challenges are for the UK Supreme Court in this moment and how well you think that the court will weather those challenges.

Lord Norton: And that’s a good question because I’m not sure how much the court, consciously if you like, could do because the court is there to hear cases and controversies. So it depends what comes before the court. You’re quite right in the government and it was in the selection manifesto was going to seek to set up a commission and perhaps limit the powers of the court. I’m not sure how much is in practice going to happen. The most we’ve seen at the moment is and they’re repealing the Fixed Term Parliament’s Act and they’ve included in the Repeal Bill – Basis Replacement Bill – an ouster clause to stop the Supreme Court having any say in relation to it. But courts are quite adept at perhaps getting around that. So there is some that there has been tension has been pressure and I’m not sure how much there will continue to be because I’m not sure I can’t see anything coming along that’s going to come before the court that’s going to be quite so controversial as the case is that it’s had to determine in recent years in relation to prorogation and in relation to withdrawal notification from the European Union. So those are European ones being dealt with that’s gone propagation was highly controversial. So I’m not sure whether they’re gonna come along now that’s really going to confront the court. And even if it does, I mean, most of what’s happened with declarations of incompatibility that the government doesn’t approve of ministers make very disobliging noises, they criticize the call. and then they get on an intrusive bill to bring the law into line what the court says it should be. And the other point is there have been some high-profile cases, high-profile declarations of incompatibility they’ve been very few. There haven’t been that many that have come um forward. So it may be that that period of controversy has passed the courts moved on of course Browner’s Hail has finished her her term she’s reached her age limit, Lord Reed has taken over. We’ll see. I think – just as an aside but it may be of interest to you as lawyers – one of my colleagues in the law the former law lord – Lord Brown of England under Hayward – made a very good point a very good article on it just how important dissenting opinions are. Because in the propagation case the court was unanimous. Lord Brown clearly thought that was possibly not a good thing because he thinks it underpins this ability for the losing claimant to have a dissenting voice that can articulate their case so they feel at least I’ve been heard and in the miller case, Miller one. Lord Reid they were dissenting it wasn’t unanimous judgment the dissenting opinions and Lord Reid did a brilliant dissenting opinion. So those who disagreed with the court thought, “Great we’ve got a champion really good case there.” And more likely to accept it than if it’s a unanimous decision. So I thought very important interesting point there. So had the court actually not been unanimous on prorogation might have taken some of the tension out of the situation. But that’s just an aside. So so I’m not sure there will be any major challenges and I’m not sure that the what the court could do in any conscious way to address those. It will depend what comes forward and how it deals with each case.

Amanda L. Tyler: That is so interesting and I’m sure Erwin and I could follow up on the on the issue of the dissenting opinions it really depends, I think, probably on the time in the context. But in this moment it it might be a quite important uh point of course in the American tradition, the primary example we offer on this issue is Brown versus Ford and a descent in that case would have been, I think, quite quite not good for the future of the country. I’m quite confident that I can – I rarely do this but – I think I can speak for Erwin on that point–

Lord Norton: Yeah we’ve got US, yeah and US versus Nixon as well I suppose you’d make a similar point so there might be odd cases like that but I think Lord Brown’s point is as a general rule it can be sort of a safety valve element to have a a really good dissenting opinion.

Amanda L. Tyler: Yes that’s really interesting. We’ve got a few minutes left and lots and lots of audience questions. It’s hard to pick they’re all so good. Why don’t I start with with this one which is a rather timely one connecting our countries and constitutional issues: the US borrowed from Britain the practice of impeachment to remove members of the executive and judicial branches. Questioner says: “I understand that impeachment has essentially disappeared in Britain. Is that is that right and is that a good thing? Is that a bad thing?”

Lord Norton: It is generally held if, I put it like that, that it has fallen into disuse because ministers are now accountable directly to parliament. So you can we can have votes of confidence remove government you no longer need the facility for impeaching ministers because really evolved from how could parliament get at the crown when you couldn’t get at the crown directly so you did it through impeaching some ministers of the crown. But it’s had quite a checkered history partly because I don’t think anybody’s fully understood what it means. And I recently was the external examiner for a whole dissertation on impeachment and the problems that it creates and whether one could actually resurrect it and for what purpose. What would it achieve that’s not already achievable through the political means. And parliament being held able to hold ministers to account because we have now the doc we do have the doctrine not just of collective ministerial responsibility but of individual ministerial responsibility so ministers collective and individually formerly are answerable to the crown but politically are answerable to parliament. So it’s a parliamentary system government rests on the confidence of the House of Commons. The House of Commons could always withdraw that confidence. So by convention the government would then have the choice of resigning or previously requesting a dissolution that’s limited under the Fixed Term Parliament’s Act but the intention is to repeal that and put the system back to what it was. So you’ve you’ve got accountability anyway. There have been occasional calls to a calls for Tony Blair as prime minister to be impeached following the Iraq war. But the practical reality is as long as the government’s got a majority in parliament anyway, you’re not going to be able to pursue impeachment and with us because it’s sp following its issues over such a long period of time. There’s the issue of even if the commons were to vote impeachment, who would try the case? Would it be the whole house of lords? Should we appoint another body? Should it be, you know, a judicial committee of the house or whatever. So there’d be all sorts of issues about how you would actually go about it even if it was deemed to be feasible to pursue impeachment. But certainly the general view is impeachment in the United Kingdom has fallen into disuse. It exists obviously um elsewhere not just in the states but other presidential system there are some parliamentary systems that retain it as well, but certainly in our case that is the general position that it’s fallen into the issues and there are calls that we might as well formally dispense with it.

Amanda L. Tyler: I’m looking– that’s so interesting and there’s so many additional comparisons and follow-ups I could ask. I so regret we don’t have more time. I’m looking at the clock, Erwin I want to give you an option to ask one more question. If not, I’ve got one I can certainly ask. We’ve got lots of audience questions, unfortunately we’re not going to be able to get to all of them.

Erwin Chemerinsky: I know we just have a couple of minutes. If I could ask one last question: what do you see the role of the courts as being now that England is separated from the European Union? Is the the courts were taking on a much greater role during the time of integration? Are the courts going to revert back to a lesser role or will it continue in the kind of more robust way that we’ve seen in recent years?

Lord Norton: Yes, I mean there are obviously consequences of withdrawing because therefore we’re not going to get the challenges between European and domestic law in the way we did. I don’t think it will have any bearing on the attitude of the courts in dealing with the cases that do come before them. It’s a bit similar like mance to the question about how the courts will now proceed what challenges they face. I think it will be dealing with cases as they come along and it may be – as I was implying earlier – that there may be a slightly lower profile given the the high profile cases that were particular to the time in the issue of gone. So I don’t envisage anything coming along that would create a problem. But having said that, as you know, cases can suddenly come along that you weren’t anticipating and I can’t see the courts if you like not rising to the challenge. And I mean the point that was when they came under a challenge including under Tony Blair, the then president of the Supreme Court – Lord Philip – the worst man Travis made the point then so did actually the Lord Chancellor Lord Faulkner, the courts are there to interpret the law. That’s their job and that’s what they’ve been doing. So that’s as far, as they’re concerned, what their role is that’s what they get on and do and they will do it without fear or favor and they are independent and they are the highest judicial minds. I mean the the members of the Supreme Court generally are absolutely brilliant jurists and and they will get on and do the job.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Thank you so much for doing this for us. Amanda I’ll give you the last word, but I learned learned so much and I look forward to when we can welcome you in person in Berkeley.

Amanda L. Tyler: I want to echo those sentiments and just say I also learned so much. I hope we will be able to have you back there are so many more things I want to talk about and it’s just been a real privilege and honor to host you, Lord Norton. I want to thank those of you in the audience who joined us. I want to thank you and I also see some in the audience, I know, have joined us from the UK and I know it’s quite late there so I’m so glad we were able to make this work and we’ve also recorded it and we’ll make it available for those who want to watch it. I know there are some who couldn’t join us live, but just a huge thank you for taking the time to talk with us about these current issues. If we were in person I would invite everyone to join us in a round of applause. I hope that we will have the honor of welcoming you back to Berkeley. Thank you again so much, Lord Norton, and thank you–

Lord Norton: My my pleasure.

Amanda L. Tyler: Wonderful. Thank you everyone for joining us today.