By Andrew Cohen

For many, sports provide a welcome oasis from our daily burdens and the world’s raging stressors. For iconic agent and alumnus Leigh Steinberg ’73, they also provide hope for a society marred by racial unrest.

During Berkeley Law’s recent annual Sports and Entertainment Conference, a student-led event organized by the Berkeley Journal of Entertainment & Sports Law, Steinberg described how pro and college sports offer a useful platform for racial harmony.

“Sports is the biggest laboratory to model good race relations we could possibly have because most Americans don’t spend a lot of time with people of other races,” said Steinberg, the inspiration for the 1996 hit movie Jerry Maguire. “In sports, people of different races spend a ton of time together and really get to know each other while working toward a common goal … You lose racist views if you can actually see people as people.”

Steinberg’s current and past client list includes some of the biggest names in sports, including reigning National Football League Most Valuable Player Patrick Mahomes. He and Damion Thomas, curator of sports at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, gave a conference keynote on advancing racial justice in sports.

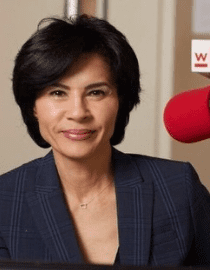

It was moderated by Jami Floyd ’89, senior editor for race and justice at New York Public Radio, who noted that “I wouldn’t be sitting here if my father didn’t get a football scholarship that eventually became a track scholarship.”

When Steinberg began representing athletes, he asked them to think carefully about how their profile could make an impact in the world. “They have a special obligation because of that stature,” he said.

Steinberg has coordinated numerous public service initiatives with clients. They’ve included a “Prejudice is Foul Play” spot with former San Francisco 49ers star quarterback Steve Young and boxing legend Oscar De La Hoya, and a “Real Men Don’t Hit Women” spot with heavyweight boxing champion Lennox Lewis.

Steinberg’s career launch is legendary. He traveled abroad after graduating from Berkeley Law, then returned to campus in 1974 and served as a dorm counselor in exchange for a free room. One undergrad he met with was Steve Bartkowski, Cal’s standout quarterback who led all of college football in passing yards that year.

Bartkowski was picked first in the 1975 NFL draft by the Atlanta Falcons but underwhelmed by their contract offer. Negotiations stalled, he fired his agent, and then stunningly hired the young Steinberg — who wound up negotiating the richest rookie deal in NFL history and went on to become one of the most renowned sports agents ever.

Debunking racial myths

Steinberg later represented Warren Moon, who played quarterback at the University of Washington. Despite Moon’s stellar college career, the NFL showed little interest.

“At that time, a generalized perception in scouting offices was that Black quarterbacks didn’t have the intellectual capacity to play that position, nor would they be great spokesmen for their owner’s brand,” Steinberg said.

Moon played six seasons in the Canadian Football League before the NFL finally came around. He signed the largest NFL contract ever at the time and eventually became the first Black quarterback voted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame — where Steinberg gave his induction speech. Today, 10 of the league’s 32 starting quarterbacks are Black.

“It’s an evolution that needed to take place,” Steinberg said. “The reason it’s critical to have Black quarterbacks is because it’s the highest profile position in all of sports. They’re the celebrities and the NFL is the most popular form of televised entertainment — five of the top 10 Nielsen ratings shows each week are NFL games. It provides a tremendous platform to speak about conditions in the inner city, police shootings, and other issues.”

While Steinberg applauded recent steps taken by pro sports teams and leagues to highlight racial injustice, including the National Basketball Association putting Black Lives Matter messaging on courts and uniforms, he urged such efforts to exceed symbolic gestures.

“It’s about teaching whites the racial history of this country,” he said. “Whites will say, ‘The Italians made it, slavery ended in 1860-something, why can’t Blacks make it, blah-blah-blah.’ But if they don’t know what happened with Reconstruction, the barriers put up by land ownership restrictions, that the New Deal uplifted everyone in America except Black people … there’s real education that has to happen.”

Thomas, the Smithsonian curator, described the growing power Black pro athletes have in connection with the greater control they have over their brands and finances. He also noted how Division I college athletes in football and men’s basketball, who create huge revenue streams for their schools, are beginning to assert leverage.

“Sports was one of the first areas of our society to integrate,” Thomas said. “African Americans viewed athletic success as a way to say to the country, ‘Look what we can do when given the opportunity to compete on equal terms.’”

Revolutionizing music

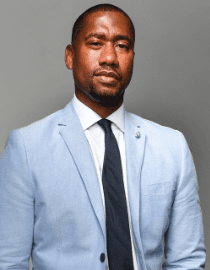

Jeff Harleston ’88 gave the conference’s other keynote, on the state of the music industry. Called “one of the most important people in music today” by moderator and Berkeley Law Professor Peter Menell, Harleston oversees all business transactions, contracts, and litigation for Universal Music Group, as well as its government relations, trade, and anti-piracy activities.

Winner of The Recording Academy’s 2020 Entertainment Law Initiative Service Award and 2018 Billboard Lawyer of the Year Award, Harleston was named to Ebony magazine’s “Power 100” list in 2017 and is annually recognized on Billboard’s list of the music industry’s most powerful executives.

When he joined the Universal Music Group in 1993, a seemingly indestructible business model seemed firmly entrenched, with CD sales increasing every year. Then the internet struck like a thunderbolt, and with it online file-sharing. Suddenly, music could be distributed without involving record companies.

“That was a radical shift overnight,” Harleston said. After the music industry adopted a combative, litigious approach to stop such downloads — first targeting providers and then uploaders — its leaders realized a different strategy would be needed.

“It’s a really bad idea to sue your customers,” Harleston said. “That’s not a well thought-out business-building proposition. As a result, we ended up becoming very unpopular for a very long time. We were great at making sound recordings and crafting songs, but not at innovating technological solutions. That was not a core competency we had, so we floundered.”

Harleston worked effectively with technology and business innovators to help create a new template for downloads and streaming platforms that sustained the music industry. He credits Apple founder Steve Jobs for steering things back on course with the advent of the iPod, iTunes, and paid downloads.

“It came at a cost as it commoditized music,” said Harleston, a member of the Berkeley Law Alumni Association board of directors. “Every song was sold at 99 cents no matter how good or not good it was, and not all songs are created equal. But it was a bargain worth taking to plug the hole in the boat.”

Other conference panels addressed women on the rise in sports, the business of esports, the year in review for amateur and professional sports, best practices for getting stories made and streamed, the evolution of corporate citizenship, and establishing a Major League Soccer team during a pandemic. Recordings of the conference can be seen here (day one) and here (day two).