Op-Ed: Trump can follow Nixon’s fear-driven playbook. But history says it won’t work in 2020

In his first public speech addressing the police killing of George Floyd and the nationwide protests, President Trump’s words took an ominous turn. Calling himself the “president of law and order,” he denounced demonstrators as an “angry mob” threatening “peace-loving citizens,” demanded that state and local governments “dominate” the protesters, and threatened to deploy the U.S. military against citizens.

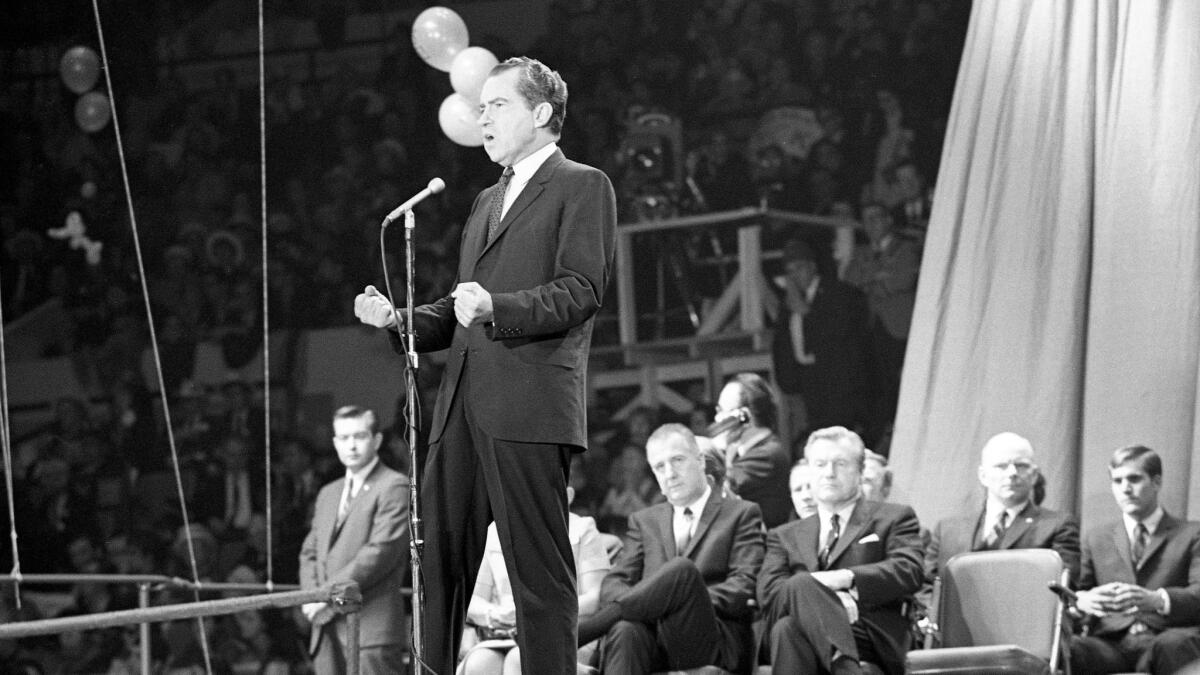

It’s likely that Trump hopes to follow President Nixon’s playbook. Trump already does so in the general sense of employing dog whistle language — phrases and imagery designed to trigger racist fears that nevertheless carry just enough ambiguity to allow plausible deniability. “I think what Nixon understood,” Trump explained in 2016, “is that when the world is falling apart, people want a strong leader whose highest priority is protecting America first.”

For Nixon, the chaos and violence of the late 1960s, even when instigated by the police, provided a resource to be exploited. He stood with the “silent majority,” Nixon said, against the “thugs” threatening the social order, be they protesters calling for racial justice or an end to the Vietnam War. Trump may believe the protests open up for him a similar opportunity. Twice on Tuesday he tweeted “SILENT MAJORITY.”

Can Trump replicate Nixon’s success in posturing against protesters? Perhaps, but there are also important differences between then and now that suggest a better outcome.

Start with the proliferation of videos showing the police killing African Americans. In the late 1960s, in the absence of visual evidence, it was easier to dismiss the claims by African Americans that police brutality and pervasive white racism justified their protests. Those realities are now a painful truth for anyone with a cellphone screen and a conscience.

The country saw the police officer with his knee on George Floyd’s neck — the officer’s sheer calmness, the casual indifference to the yells to stop by horrified onlookers. Floyd’s shallow, gargled plea, “I can’t breathe,” echoing the final gasps of Eric Garner as he too succumbed to police violence, another death watched by the nation.

These videos join a stream of many others this decade — most recently of a black jogger shot to death in broad daylight as two white vigilantes confronted him on a quiet residential street, and of a white woman in Central Park weaponizing her whiteness by calling the police to falsely report that her life was being threatened by an African American man who asked her to leash her dog.

Another big change involves the much-diminished receptivity of many whites to claims that there’s something inherently violent and dangerous about African Americans. While many remain susceptible to this stereotype, the racial attitudes of very large numbers of whites have shifted remarkably over the last 50 years. Barack Obama’s election both reflects this trend and accelerated it, as the decency he and his family projected from the White House challenged the racial lies many whites have inherited.

Among Democrats in particular, social scientists have documented major shifts toward racially egalitarian views. This most probably reflects, in addition to admiration for Obama, negative perceptions of Trump. By campaigning and governing on themes of racial resentment, Trump has made himself the public face of white pride. For many whites, it’s an ugly visage: lying, self-absorbed, bullying.

Nixon was a moderate Republican when he ran for president in 1968, with more room to present himself as the embodiment of American rectitude, which helped him pull many whites from the Democratic camp. Trump has rarely increased his level of public support. His fearmongering about the protests may energize his base, but is unlikely to expand it.

Nevertheless, there’s one similarity that may yet develop and could shift people toward Trump. The late 1960s saw lengthy stretches of protests. So far, the country has endured less than 10 days of demonstrations. But there’s an ominous likelihood that this week’s turmoil presages a long, hot summer.

It’s not simply that the police will continue to strike the matches. The pandemic will probably continue providing gasoline. People in poor communities and communities of color are more likely to fall ill and to die from the coronavirus. They are suffering the greatest levels of job loss and the highest levels of hunger. They’re also the workers forced to risk their health to keep the economy running. There’s little reason to think that the pain and dislocation caused by the pandemic will ease in the next few months.

Prolonged turmoil could make people more receptive to Trump’s promise to impose stability and order. In 2016, Trump, in explaining how his style reflected Nixon’s, said, “The ’60s were bad, really bad. And it’s really bad now. Americans feel like it’s chaos again.” As the summer heats up, these words might ring true with more and more voters.

Like Nixon, Trump and his campaign depend on promoting a vision of the United States as locked into a conflict between innocent white people and dangerous minorities. Trump hopes to make the protests proof of that narrative.

But Trump alone cannot write our story. So far, the protesters — and support for the protesters — have come from every racial group. This is key. People of every color must continue to publicly challenge police brutality and to champion racial equality. It’s the moral thing to do.

And it’s also the best way to defeat Trump’s efforts to promote and capitalize on racial conflict. People of color are not the threat this country faces. It’s politicians who stoke division to win power. Together, and only together, we stop this threat by voting them out.

Ian Haney López is a law professor at UC Berkeley and the author of “Merge Left: Fusing Race and Class, Winning Elections, and Saving America.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.