Image by Queven from Pixabay

Inequality During the Coronavirus Pandemic

Currently, the COVID-19 diagnosis total is over 2 million. The United States has roughly 31% of the total number of cases worldwide. The virus does not seem to discriminate. It is hitting the elite including dignitaries such as Prince Charles of Wales, athletes such as Kevin Durant, entertainers such as Idris Elba, Tom Hanks, and Rita Wilson, journalists such as Chris Cuomo, politicians such as U.S. State Senator from Kentucky Rand Paul, the British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, and even academics such as Harvard University President Lawrence Bacow.

But, while COVID-19 seems to be an equal opportunity disease, the U.S. healthcare system is not immune from inequality. The U.S. healthcare system is embedded with systemic inequalities that collide on the most oppressed, marginalized, and vulnerable populations. Social distancing and stay at home orders are implemented in most places in the United States. However, telework and social distancing are privileges that evade low-wage workers, many of whom are Black Americans and Latinos. Both groups are overrepresented among grocery workers, restaurant workers, cleaners, and transit drivers. Some of the hardest hit populations include the elderly who are in facilities, incarcerated people, and the homeless.

This wave of the Contexts Magazine special issue on COVID-19 addresses the myriad of ways inequality is manifesting during this pandemic. They focus on workers, shelter, food, prisons, and racism. Accordingly, it is important to note that these inequalities are not new. Instead, COVID-19 is bringing these inequalities front and center, and inequality is exacerbated during crises rather than reduced.

– Rashawn Ray and Fabio Rojas

-

-

- ” Race, Gender, and New Essential Workers during COVID-19” by Nicole A. Pangborn and Christopher M. Rea

- ” Paid Leave for Precarious Workers during COVID-19” by Catherine Albiston

- “The Effect of COVID-19 on the Food System” by Kara Young, Jared Strohl, Sarah Bowen, Yuki Kato, Justin Schupp, Anne Saville, Alison Alkon, Nino Bariola, and Ferzana Havewala

- ”Impact of Coronavirus on the U.S. Restaurant Industry” by Amanda Michiko Shigihara

- ”The Privilege of Social Distancing” by Kimberly Higuera

- ”The Shortcomings of Shelter-in-Place During a Pandemic” by Monica J. Casper

- “Prisons as a Public Health Threat during COVID-19” by Lucius Couloute

- ”Homeless Children and COVID-19” by Yvonne Vissing and Diane Nilan

- ”Bodies in Places: Addressing Domestic Violence in a Pandemic” by Marie Laperrière and Kartikeya Bajpai

- ”Return Migration During a Pandemic” by Hansini Munasinghe

- “Anti-Asian Hate During COVID-19” by Myron T. Strong and Nancy Wang Yuen

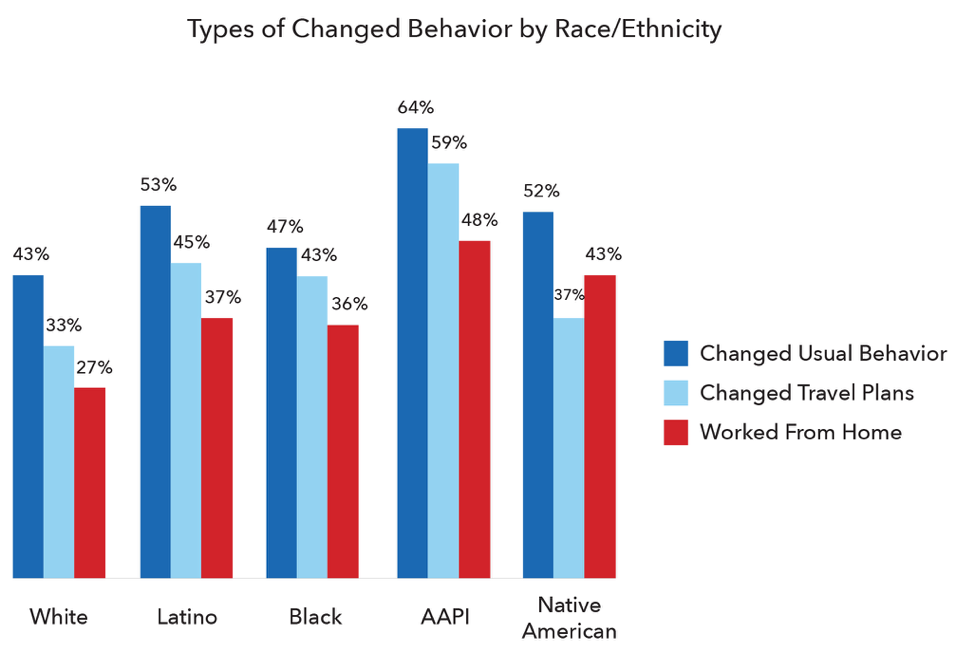

- ”Structural Inequalities and Not Behavior Explain COVID-19 Racial Disparities” by Gabriel R. Sanchez, Melanie Sayuri Dominguez, and Edward D. Vargas

- ”The Employment Armageddon Facing the U.S. Restaurant Industry” by Eli R. Wilson

-

Race, Gender, and New Essential Workers during COVID-19 by Nicole A. Pangborn and Christopher M. Rea

“Crazy how grocery store workers had no idea they signed up for the draft,” Twitter user @blairsocci noted on March 16, 2020. Around the same time, public health officials across the United States began encouraging Americans to stay at home – with the exception of leaving for “essential activities,” like buying groceries – to slow the spread of COVID-19. Since then, store clerks, sanitation workers, bus drivers, and healthcare workers have found themselves among those on the front lines of a pandemic.

Staying home, health experts say, is a means of social distancing — reducing the amount of close physical contact between individuals. Social distancing cuts the number of opportunities for person-to-person transmission, slowing the (inevitable) spread of the virus and lessening the burden on the nation’s healthcare system. In order to promote social distancing, by March 24, 2020, all 50 states had recommended or ordered the closure of schools; governors and mayors across the country had ordered restaurants and businesses to switch to takeout and delivery; in-person gatherings, religious services, weddings, and funerals had been cancelled or strongly discouraged; universities had switched to online teaching; and companies all over the world had asked employees to telecommute.

But telecommuting isn’t possible for everybody.

As Twitter user @le___RATO put it on March 17, 2020, “S/O [shout-out] to all the taxi drivers/uber driver[s]/train drivers/bus drivers who are still operating. Not everyone has the luxury of working from home.”

The idea of social distancing is not new. In early October 1918, during the Spanish Flu pandemic, the city of St. Louis ordered residents to close “all theaters, moving picture shows, schools, pool and billiard halls, Sunday schools, cabarets, lodges, societies, public funerals, open air meetings, dance halls and conventions.” The intervention, which remained in effect until December 28 of that year, worked: social distancing successfully reduced the city’s excess death rate compared to places like Boston and Philadelphia.

But 100 years later, there is a new dimension to social distancing. Some workers can work from home and continue to receive a paycheck, sheltered from the virus behind their computer screens. Others cannot.

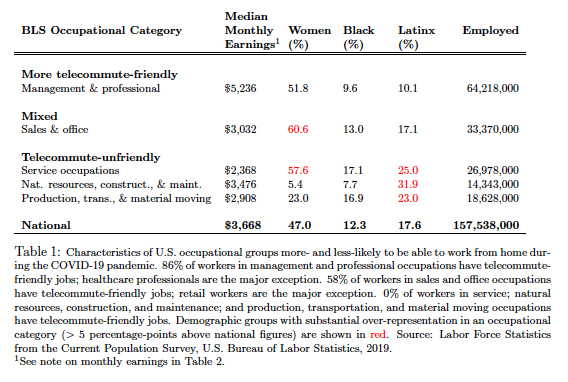

A quick look at some basic data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reveals some of these emerging inequalities (Table 1). First, there seems to be a class divide between those who can easily transition to working from home and those who can’t: the median monthly earnings of the 64 million Americans in management and professional occupations – people who are now mostly working from home – is more than twice that of the 27 million home health aides, cooks, janitors, childcare providers and other service workers who mostly have to work on-site to earn a paycheck.

First, there seems to be a class divide between those who can easily transition to working from home and those who can’t: the median monthly earnings of the 64 million Americans in management and professional occupations – people who are now mostly working from home – is more than twice that of the 27 million home health aides, cooks, janitors, childcare providers and other service workers who mostly have to work on-site to earn a paycheck.

Second, there are also some important gender-based differences between those who can and cannot easily work from home. Around 60% of workers in sales and office professions – administrative assistants, bank tellers, customer service reps, retail clerks – are women; about 42% of this group hold jobs not amenable to telecommuting. On the other hand, men make up nearly 95% of the 14 million workers in occupations related to natural resources, construction, and maintenance. None of this work is telecommute-friendly; one cannot frame building walls, lay rail track, or repair buses from home.

Third, racial and ethnic differences also emerge. Latinx workers are heavily over-represented in telecommute-unfriendly professions, like construction and automotive repair. Self-identified “Hispanic or Latino” individuals make up about 18% of the U.S. workforce but fully 36.4% of the 8.3 million construction and extraction workers; nearly 32% of all workers in natural resources, construction, and maintenance occupations as a whole; and fully a quarter of all service workers.

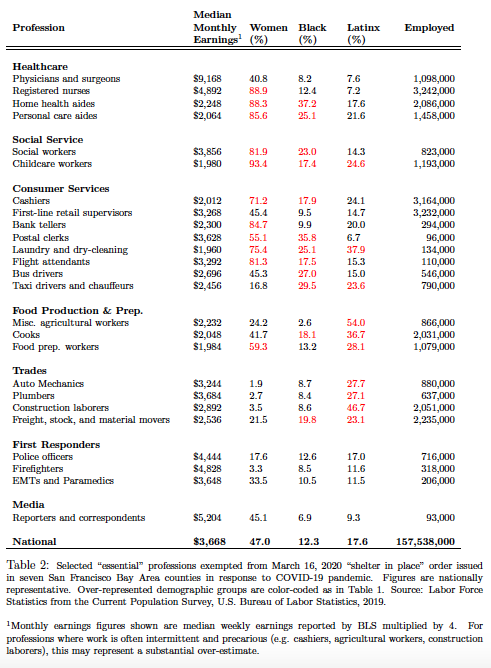

To get an even more finely grained sense of these disparities, we gathered data on occupations specifically designated as “essential” in the recent shelter in place orders issued in the San Francisco Bay Area (Table 2).

Monthly earnings figures shown are median weekly earnings reported by BLS multiplied by 4. For professions where work is often intermittent and precarious (e.g. cashiers, agricultural workers, construction laborers), this may represent a substantial over-estimate.

Aside from physicians and surgeons, the healthcare professionals on the front lines of the COVID-19 epidemic are overwhelmingly women. So are social service workers, childcare providers, home health aides, and consumer service workers, like retail cashiers, bank tellers, and flight attendants. (Taxi drivers are a notable exception; they are mostly men.) Many of these female-dominated professions put workers at especially high risk of infection: they involve being in close proximity to other people and high probabilities of exposure to the virus.

Men are heavily over-represented in blue-collar work also deemed “essential,” but many of these professions are at somewhat lower-risk in the midst of a viral outbreak: construction work, auto repair, and freight, for example, involve lower levels of interaction with the public and fewer chances of disease transmission.

Most workers designated as “essential” earn less money than the national median and are disproportionately likely to be people of color. Despite the fact that about 12% of the workforce identifies as Black and 18% identifies as Latinx, more than half of agricultural workers, over a third of cooks, and nearly 30% of food preparation workers – all designated as “essential” in the recent Bay Area orders – are Latinx, and over a third of postal clerks and 27% of bus drivers identify as Black. These essential employees remain hard at work across the country.

As we mount a national response to the global COVID-19 pandemic, taking account of these demographic differences in work is important. Emergency responses that put particular groups – people of color and women – at higher risk stand on morally shaky ground: there is no reason that one segment of the population ought to bear the brunt of a viral scourge. But early data suggest that this is precisely what is happening. In Michigan, for example, Black Americans make up 14% of the state population but 40% of coronavirus deaths. And in New York City, the coronavirus seems to be twice as deadly for Black and Latinx people compared to whites.

COVID-19 has transformed the world for all of us, but the data make it clear: it is not transforming in the same way for everyone.

As novelist Matt Haig (@matthaig1) commented on Twitter on March 17, “It’s a strange irony that the people whose wages have been suppressed for years by governments who have devalued them, are the ones expected to be on the front line in a time of crisis.”

Nicole A. Pangborn is a Lecturer in the Sociology Department at The Ohio State University where they research gender, social networks, race and ethnicity. Christopher M. Rea is an Assistant Professor of Public Afffairs at The Ohio State University where they study the politics and economics of environmental governance and regulation.

Paid Leave for Precarious Workers during COVID-19 by Catherine Albiston

Covid-19 reveals what the second great transformation from good jobs to bad jobs means for workers’ economic security. The economy in developed countries has shifted from good jobs—full time permanent employment with paid leave, health insurance, and retirement benefits—to bad jobs and gig engagements that lack these characteristics (Kalleberg, Reskin and Hudson 2010, Kalleberg 2011). In a phenomenon Jacob Hacker (2004) calls “policy drift,” social policies have not kept pace, shifting the risk of both ordinary downturns and catastrophic events onto workers and their families. Low-wage workers in precarious employment are the most likely to lack these protections and the most exposed to risk in the current crisis.

Countries vary in their responsiveness to these developments, but the United States is an extreme outlier on one key factor in the current crises – paid leave. As the World Health Organization notes:

Paid sick leave plays a crucial role especially in times of crises where many workers fear dismissal and discrimination when reporting sick. In fact, the absence of paid sick days forces ill workers to decide between caring for their health or losing jobs and income, choosing between deteriorating health and risking to impoverish themselves and often their families (Scheil-Adlung and Sandner 2010).

Yet the United States is virtually alone in providing no federally mandated paid sick time or paid family leave (Raub et al. 2018a, 2018b). Private provision of these benefits follows predictable patterns of inequality. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2019) indicates that that access to paid sick leave is greater for full time than part time workers, high earners compared to low earners, public sector relative to private sector workers, and those who work for larger employers relative to smaller employers. Only 16% of American private-industry employees have access to paid family leave through their employer, with more access among highly paid occupations, full time workers, and workers in large companies (Donovan 2018). Although some states have adopted paid leave programs, these are recent and partial.

Lack of paid leave forces impossible choices for workers between working sick or losing their jobs, and it leaves families without the care and economic support they need. Workers who lack paid leave are more likely to go to work sick, more likely to forgo medical care for sick family members, and more likely to experience unemployment (DeRigne, Stoddard-Dare and Quinn 2016). By contrast, Hill (2013) found access to sick leave decreases the probability of job loss by 25%.

Lack of paid leave also amplifies patterns of inequality driven by caregiving more generally. Caregiving for children and sick or elderly family members is not optional, and someone must bear the cost of that care. Wealthier families are better able to absorb the cost of private caregiving, but lower-paid workers have few options other than providing the care themselves at the expense of their paycheck. Two-parent families can share care and earning responsibilities, whereas single parent families, which are at least as prevalent as dual worker families, must meet both responsibilities with one adult earner. Women disproportionately provide care to children and sick family members, and disproportionately bear the economic costs in terms of lost employment and lost income (Doran, Bartel and Waldfogel 2019).

Paid leave policies shift some of these costs onto employers and the state, or spread the risk of these costs through state-mandated leave programs paid for by employee payroll deductions. Countries with paid leave provisions reduce the impact of illness on family and worker economic stability and welfare for the ordinary illnesses and caregiving realities of life. What these policies recognize is these forms of insecurity for working families are nothing new; workers face them every day, just not all at the same time. But Covid-19 multiplies the individual mitigating effects of paid leave by millions, and universal paid leave reduces the inequality-amplifying effects of crises like Covid-19. Although many workers will lose their jobs in the upcoming economic downturn, a few weeks of paid leave to recover from illness and care for ill family members may make the difference between bridging this public health challenge and complete economic disaster for many working families.

On March 18, 2020, the United States enacted the Families First Corona Virus Response Act, providing two weeks paid sick leave and partially-paid family leave for up to twelve weeks, amended less than 10 days later by the Corona Virus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act. The legislation acknowledges the new precarious economy by covering workers who have been on the job for as few as thirty days and pro rating pay for part time workers. Importantly, the legislation prohibits employers from retaliating against employees for taking paid leave, which research shows is a concern that discourages workers from taking leave even when they have it (Milkman & Appelbaum 2013, Albiston & O’Connor 2016). The leave provisions are far from universal, however. Pay per day is capped at $511 per day for sick leave, but only $200 or 2/3 pay (whichever is smaller) for family leave, even though lost wages do not vary with the reason a worker needs leave. The law excludes employers with 500 employees or more, which constitutes more than half the workforce, including employers like FedEx and Amazon that remain open during this crisis. It permits the Department of Labor to exempt small businesses. Health care workers can also be excluded at the discretion of their employers. Finally, this law is a short-term legislative fix that expires on December 31, 2020. In short, this law won’t change the structural reality around precarious work, inadequate paid leave, and economic inequality and insecurity in the United States.

Covid-19 is indeed a global emergency, but for millions of families, the lack of paid leave in the United States has been an emergency for a long time. This isn’t a new problem, only one that is newly visible in this simultaneous health care crisis for everyone. Perhaps the long-term comparative welfare of families in countries with adequate paid leave and the few, like the United States, without it, will show the folly of ignoring this emergency for too long.

References

Albiston, Catherine, and Lindsey Trimble O’Connor. 2016. “Just leave.” Harvard Women’s Law Journal 39:1-65.

Families First Corona Virus Response Act, Public Law No: 116-127, 116th Congress (2019-2020).

Corona Virus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, Public Law No: 116-136, 116th Congress (2019-2020).

DeRigne, LeaAnne, Patricia Stoddard-Dare, and Linda Quinn. 2016. “Workers without paid sick leave less likely to take time off for illness or injury compared to those with paid sick leave.” Health Affairs 35(3):520-527.

Donovan, Sarah A. 2019. Paid family leave in the United States (CRS Report R44835). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service.

Doran, Elizabeth L., Ann P. Bartel, and Jane Waldfogel. 2019. “Gender in the Labor Market: The Role of Equal Opportunity and Family-Friendly Policies.” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences5(5):168-197.

Hacker, Jacob S. 2004. “Privatizing risk without privatizing the welfare state: The hidden politics of social policy retrenchment in the United States.” American Political Science Review 98(2):243-260.

Hill, Heather D. 2013. “Paid sick leave and job stability.” Work and occupations 40(2):143-173.

Kalleberg, Arne L., Barbara F. Reskin, and Ken Hudson. 2000. “Bad Jobs in America: Standard and Nonstandard Employment Relations and Job Quality in the United States.” American Sociological Review 65(2):256-78.

Kalleberg, Arne L. 2011. Good jobs, bad jobs: The rise of polarized and precarious employment systems in the United States, 1970s-2000s. Russell Sage Foundation.

Milkman, Ruth, and Eileen Appelbaum. 2013. Unfinished business: Paid family leave in California and the future of US work-family policy. Cornell University Press.

Raub, Amy, Paul Chung, Priya Batra, Alison Earle, Bijetri Bose, Judy Jou, and J. Heymann. 2018a. “Paid leave for personal illness: A detailed look at approaches across OECD countries.” WORLD Policy Analysis Center. Retrieved March 23, 2020. (https://www.worldpolicycenter.org/sites/default/files/WORLD%20Report%20-%20Personal%20Medical%20Leave%20OECD%20Country%20Approaches_0.pdf)

Raub, Amy, Alison Earle, Paul Chung, Priya Batra, Adam Schickedanz, Bijetri Bose, Judy Jou Chorny, N.D.G., Wong, E., Franken, D. and Heymann, J. 2018b. “Paid Leave for Family Illness: A Detailed Look at Approaches Across OECD Countries.” Retrieved March 23, 2020. (https://www.worldpolicycenter.org/sites/default/files/WORLD%20Report%20-%20Family%20Medical%20Leave%20OECD%20Country%20Approaches_0.pdf)

Scheil-Adlung, Xenia, and Lydia Sandner. 2010. “The case for paid sick leave.” World health report. Retrieved March 23, 2020. (https://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/financing/healthreport/SickleaveNo9FINAL.pdf)

U.S. Dep’t of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. September 2019. Bull. No. 2791, National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in the United States.

Catherine Albiston is a professor of Sociology at University of California, Berkeley. Their research addresses the relationship between law and social change.

The Effect of COVID-19 on the Food System by Kara Young, Jared Strohl, Sarah Bowen, Yuki Kato, Justin Schupp, Anne Saville, Alison Alkon, Nino Bariola, and Ferzana Havewala

In the midst of the COVID-19 global crisis, we are witnessing deep and sudden disruptions to our global food system that are sending producers, laborers, and consumers into a tailspin. On the production side, links in our food supply chain from farm to table have been temporarily halted. Small and medium-scale farmers grapple with how to stay in business as farmers’ markets are suspended. Although food suppliers in the United States assure consumers that there is plenty of food, grocery stores find it difficult to meet the chaotic food demands stemming from the uncertainty of the virus. Food banks and pantries are working at capacity and are in dire need of volunteers to serve the swelling population of Americans going hungry. Restaurants, bars, and coffee shops have been mandated to temporarily close, leading to potential losses of up to 7 million jobs over the next three months. At the same time, food system workers like shelf stockers, supermarket clerks, and farmworkers are on the frontlines of the crisis still working despite the declaration of social distancing.

The consequences at the intersection of this pandemic and food system failures impact consumers too. People around the United States see empty shelves in the bread aisle and long lines at grocery stores and wonder how they are going to make do without key staples. As schools around the country close, communities worry about how to feed the millions of kids who depend on school meals. And although the first coronavirus relief package includes more than $1 billion in food assistance, this still might not be enough to ensure that everyone impacted by this crisis gets the food they need.

These pandemic-triggered ruptures in our food system shine a glaring light on social relations that have otherwise been invisible. Our global food system and food security are fundamentally built on inequality and exploitation. Here are three realities of the food system that the coronavirus crisis exposes:

Food System Workers are Essential and Exploited

The food industry is the largest employer in the country, employing 14% of the country’s workforce (21.5 million workers). Food system workers are also paid the lowest hourly wages of any wage workers in the United States, and roughly 82% of food system workers are in precarious frontline positions in which they have little job security. Ironically, this leads to a situation where food system workers are more food insecure than workers employed in other sectors of the economy. In addition, these inequalities are exacerbated based on race and gender, with nonwhite food workers, and particularly women of color, earning significantly less than their white and male counterparts. As a share of income, Americans pay less for their food than almost any other country in the world, in part because workers are paid so little (also see here).

In this pandemic, which the president has labeled a ‘war’ against an ‘invisible enemy’, it is these workers who are on the front lines. The death of a Costco employee makes it clear who is putting their bodies at risk so that other people can stay at home. In addition to health care workers, it is the people who pick produce, stock supermarket shelves, drive the trucks, stand at cash registers, and deliver food to your door. Unfortunately, in a country that is characterized by high degrees of inequality by race, class, and gender, these workers are disproportionately low-income, Black, Latinx, immigrants or undocumented. In other words, while privileged Americans close themselves inside their homes and order their food to be delivered, low-income communities and communities of color are staying at work or losing their jobs. These frontline food workers are being asked to unequally shoulder the risk of COVID-19 now and will undoubtedly shoulder a larger burden of economic and food insecurity in its aftermath.

Food is Social

Shelter-in-place mandates and social distancing are necessary to protect the public good by slowing the spread of the COVID-19 virus. At the same time, they have profound effects on our social practices. The rise of virtual happy hoursand coffee breaks illustrate people’s desire to connect over food, even when they must stay in their houses. For many, comfort eating and cooking—taking the time to bake cookies together or make a favorite family dish—have become quarantine survival strategies and ways of producing joy in these uncertain times.

At the same time, the current crisis illustrates how food not only brings people together, but also serves as a source of social division. Xenophobic tropes that blame China, and Chinese people, for spreading the coronavirus are tied up with images of food. Texas Senator John Cornyn, for example, claimed that Chinese people “eat bats and snakes and dogs and things like that,” alluding to a debunked myth that the virus originated with a woman who ate bat soup. This message is just one of many examples circulating in the media that buttress a racist and imperialist discourse about this pandemic that implies that “dirty” or “questionable” foodways of non-white, non-Americans are to blame.

The Effects of Crisis are Uneven

This virus—which, unlike humans, does not discriminate—exposes inequalities that have been embedded within our institutions and cultural ideas about one another all along. We can see how this plays out with food. Even before the outbreak and during a relatively prosperous economic period, 1 out of 9 U.S. households were experiencing food insecurity. This rate of food insecurity in the United States is high compared to most other rich democracies. Furthermore, food insecurity is more prevalent in households with children and in female-headed households, Black and Latinx-headed households, Native American households, and households headed by people with disabilities. Because these inequalities are institutionalized, those with privilege all too often turn a blind eye—food in this country is abundant, if you can afford and access it. When we pair these already food insecure populations with the millions of workers that are currently losing their jobs due to COVID-19, we are bound to see a population of hungry people skyrocket unequally along these same race, class, and gender lines. Because of this, just figuring out how to feed ourselves during this crisis is insufficient.

What the food system is revealing to us during this unprecedented time of crisis is deep inequality masquerading as business-as-usual. Eventually, this pandemic will end. However, the structural inequalities that exist at the root of American capitalism will remain, or worsen as a result of the crisis, unless we take drastic measures to fundamentally change the system.

Kara Young is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology at The Ohio State University where she studies how inequalities of race, class and place shape people’s daily food consumption practices and food related health aspirations in urban contexts. She also spearheaded the creation of the Coalition of Food and Agricultural Sociology.

Jared Strohl is a Doctoral Candidate of Sociology at the University at Buffalo where they study food justice, ecological sustainability, social movements, and the sociology of knowledge.

Sarah Bowen is Associate Professor of Sociology at North Carolina State University, where she studies food insecurity and family foodwork.

Yuki Kato is Assistant Professor of Sociology at Georgetown University. Her areas of research and teaching focus on urban studies, food justice, and environmental justice.

Justin Schupp is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Wheaton College.

Anne Saville is an Adjunct Professor of Sociology at Flagler College. She specializes in environmental justice through all aspects of food and agriculture and intersectionality.

Alison Hope Alkon is Associate Professor of Sociology at University of the Pacific. She studies, teaches and writes about the ways that racial and economic inequalities effect and are effected by the ways that societies produce, distribute and consume food.

Nino Bariola is in the Sociology department at University of Texas at Austin, where he studies food, food work, and inequality.

Ferzana Havewala is an Assistant Professor in the College of Public Affairs at the University of Baltimore. Her central line of research examines the quantitative links between residential segregation and the food environment and in turn, the impact on food security.

Impact of Coronavirus on the U.S. Restaurant Industry by Amanda Michiko Shigihara

Despite past economic hardships in the United States (e.g., The Great Recession of 2008), the U.S. restaurant industry has continued to flourish in terms of annual sales and job opportunities. According to the National Restaurant Association (NRA), the restaurant industry’s annual sales have grown from $43 billion in 1970 to over $860 billion in 2019. Furthermore, the total economic impact of the restaurant industry is more than $2.5 trillion because every dollar spent in the industry leads to 2 dollars paid to other industry employees (e.g., purveyors, farmers, alcohol distributors, Point of Sales software developers, construction laborers, maintenance and repair workers, electricians, cleaners, etc.). Today, the restaurant industry is the nation’s second largest private-sector employer, employing roughly 15.6 million people or 10 percent of the U.S. workforce. Indeed, these figures make the far-reaching economic importance of food and beverage establishments apparent.

Prior to the coronavirus (COVID-19), the NRA projected that 2020 would see $899 billion in sales among its more than 1 million restaurant locations and an increase of 1.6 million workers by 2030. However, it is clear that COVID-19 is threatening the livelihood of the U.S. restaurant industry and its employees because of public-space avoidance, shelter-in-place orders, mandatory restaurant/bar shutdowns, and modified service (i.e., takeout and delivery only), all of which will have long-lasting devastating economic impacts. In fact, on March 18, 2020, the NRA anticipated a loss of $225 billion as well as 5 to 7 million jobs during the next 3 months alone. Small family-owned, mom-and-pop, single-unit, dive, and franchise-type eating and drinking places as well as employees stand to experience the consequences of the actions to mitigate COVID-19 the most. Many of these establishments have been forced to lay off workers and shut down temporarily. Consequently, restaurant analysts have estimated that 75 percent of these closed-down independent restaurants are likely to go out of business permanently.

Regardless of the beneficial role that the restaurant industry has played in the U.S. economy, the low wages, minimal benefits, limited stability, and fire-at-will policies in restaurant industry jobs have earned them the designation of “bad jobs.” In addition, restaurant industry positions are overwhelmingly part-time (< 35 hours/week), hourly-paid, and do not guarantee full healthcare coverage. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) indicates that part-time work is more common in the restaurant industry than in any other industry, and most part-time food and beverage employees earn a tipped minimum wage. While the federal minimum wage is $7.25, tipped employees are only required to earn the federal tipped minimum wage of $2.13; each state has discretion over its tipped minimum wage (16 states permit $2.13/hour). The annual mean income for restaurant industry occupations is $25,580. Notwithstanding the effects of COVID-19, restaurant industry employees potentially struggle to make-ends-meet. Therefore, without daily employment, the vast majority of restaurant industry workers will not receive an income, and those who were living pay-check-to-pay-check might not be able to buy essential goods. As opposed to popular belief, restaurant industry jobs are not simply temporary or for “pocket change,” they are people’s permanent careers and livelihood. Ultimately, numerous restaurant workers will incur debt and have difficulty getting another job or entering a different industry immediately, many of whom might not have the résumé to do so.

Having worked in restaurants for almost 14 years (2000-2014), I am particularly aware of how employee layoffs as well as restaurant shutdowns and closures have huge economic impacts for restaurant industry employees, especially for those with various financial responsibilities but little to no savings. Between 2009 and 2014, I interviewed 52 adult restaurant industry employees from California and Colorado (states that have counties with shelter-in-place orders because of COVID-19). The vast majority of these workers fell into the economically-vulnerable group of part-time, hourly-paid employees. In addition, they typically reported low annual incomes (between $2,400 and $53,000) with an average income of $26,457.69, similar to the current national average mentioned above. At the time of these interviews, the majority of the participants’ employment durations ranged between 6 and 25 years. Although it has been 6 years since I completed this study, I have contact with some of the participants, and they revealed feeling the economic impact of restaurant shutdowns, layoffs, and/or modified schedules. For participants with whom I have no contact, if they remained employed in restaurants, I strongly suspect they too are experiencing economic and employment insecurity. During interviews, the participants did not speak of financial contingency plans in the case of U.S. disasters, however, they talked about their precarious circumstances because of nontraditional work hours, uncertain wages and tips, minimal to no healthcare coverage, and inadequate financial as well as social safety nets.

In the absence of major and unprecedented government intervention, the restaurant industry will be forever changed. What can be done? The NRA wrote a letter to President Trump and Congress on March 18, 2020 requesting that the U.S. Treasury Department provide a $145 billion Restaurant and Foodservice Industry Recovery Fund, $35 billion for Community Development Block Grants for Disaster Relief, $100 billion in Federally-Backed Business Interruption Insurance, and other help, such as mortgage/tax deferrals and disaster unemployment aid. It would behoove the U.S. government to assist, as the restaurant industry is central to the U.S. economy, not to mention that it employs more women and minority managers than any other industry, and we know that women and people of color are disproportionately affected by health disparities.

Recommended Resources

National Restaurant Association. 2020. “Research & Trends.” Retrieved March 18, 2020 (https://restaurant.org/research).

Shigihara, Amanda M. 2018. “‘(Not) Forever Talk’: Restaurant Employees Managing Occupational Stigma Consciousness.” Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management 13(4):384-402.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2020. “Overview of BLS Wage Data by Area and Occupation.” Retrieved March 18, 2020 (https://www.bls.gov/bls/blswage.htm).

Amanda Michiko Shigihara is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at California State University, Sacramento. She has published several articles on the restaurant industry.

The Privilege of Social Distancing by Kimberly Higuera

A video recently made the social media rounds. It shows people in a New York City apartment, hanging out of their respective windows yelling at the pedestrians walking below: “Flatten the curve, go home! Get the f*** inside!” The speakers even clap along with the syllables of their admonishing message for emphasis. Another similar video in New York City shows a man on his fire escape reciting information about the COVID-19 public health guidelines and specifically referencing certain people as they walk by: “Yeah dude with the medicine could be spreading it to that guy right there with the stroller.” Stigmatizing socially undesirable behavior in order to get people to change their ways is not a new technique. It has been employed by everyone from national governments to schools to family members.

Stigma is a cheap way for governments to incentivize compliance while still having very real implications for the stigmatized. In admonishing their fellow New Yorkers, the people captured in the videos were all employing public stigma to try to get others to perform “social distance” or “measures taken to restrict when and where people can gather to stop or slow the spread of infectious diseases” in order to eventually tackle the COVID-19 pandemic. What is lost in the effort to stigmatize people who do not socially distance themselves is the class divide within this group of people. Perhaps because many of the most visible cases of people ignoring the call for social distance are young people posting on social media about drinking at bars or partying for spring break, people admonish anyone who doesn’t stay home as if they were all millennial partyers. In a recent video shared on Twitter actress Hilary Duff verbalized what many were already thinking: “To all you, young, millennial assholes that keep going out and partying: go home. Stop killing old people, please.”

However, there is another group of people who are not socially distancing: the precariously employed, that is to say workers who live paycheck to paycheck and/or lack the flexibility to stay home. To the precariously employed staying home from work for health reasons is a decadent luxury, one that they don’t usually employ even outside of the context of a pandemic.

During my time as a fellow with Stanford’s Immigration Policy Lab, myself and Dr. Tomas Jimenez managed an interview study with 50 undocumented and DACA recipient immigrants on intergenerational health in the communities of some of the most precariously employed in the United States. What shocked me the most was not that the people we spoke to could not access health services, but rather that the respondents themselves saw using services as a decadent, borderline selfish thing to do while living in a home where money was always tight. Health was a resource that had to be budgeted and could only be granted to the children or elderly in the household. One of the interviewees, Lalo, a middle-aged man struggling to cope with his diabetes put it succinctly: “You realize you can’t afford your own disease… Am I just going to spend money on something that doesn’t have a solution?” Lalo weighed spending money on his diabetes against spending money on his children, the eldest of which was constantly ill, and decided on the latter. Healthcare was for the children and elderly in the family, and for everyone else healthcare was discussed as a kind of pampering self-care. Things that are broadly considered as essential to maintaining health like administering insulin, staying home from work after chemotherapy, or getting a dental check-up were discussed as if they were facemasks, massages, or aromatherapy. Adela, a young woman who supported herself and her mother, referred to going to the dentist and financing her braces as “my moment of treating myself.” When you live under constant economic stress healthcare becomes self-care. Taking care of your health becomes a luxury that you cannot afford, even in a pandemic.

The precariously employed are perhaps also some of the most vulnerable to other types of social stigma. They experience the stigma of poverty that has long been documented in US politics and policy. In the case of my interviewees, they experienced the highly palpable stigma of being migrants, and the highly punishable stigma of being undocumented. Stigmatizing the precariously employed who cannot afford to socially distance themselves is therefore a complex, intersectional process. When we stigmatize all people who do not socially distance themselves as if they are all privileged millennials, we are applying stigma onto a group that is likely already experiencing other forms of it. What’s more as social scientists we know that stigma has real consequences. It can impact whether people who cannot afford to socially distance themselves actually end up seeking medical attention and whether they feel they will not be blamed for contracting the coronavirus. Or it can simply impact whether or not those who could not afford to stay home get cursed out from a window, lectured from a fire escape, or just generally admonished in the street by people who could afford to stay home.

In writing this, I am not calling on people to stop leveraging stigma to get people to socially distance themselves, but I am calling on people to consider the many social factors that can impede people from staying home. I am calling on people to consider the sparse American safety net that pushes people out of their homes during a pandemic. The United States’ lack of social and economic support for workers and the poor specifically, has long had negative health consequences. It is simply during the COVID-19 pandemic that the negative health effects of widespread economic precarity are on display not just in how they impact the precariously employed themselves but the health of the entire country. Social stigma can be a powerful tool when it is directed towards people who have the viable option of staying home. On the other side of the “social stigma can be a powerful tool” coin is the fact that stigmatizing people who do not have the viable option of staying home is an act of privilege and one that could end up hurting the likelihood of the precariously employed from reaching out if they do end up needing medical attention.

Kimberly Higuera is a Doctoral Candidate of Sociology at Stanford University where they research policy, immigration, and race and ethnicity.

The Shortcomings of Shelter-in-Place During a Pandemic by Monica J. Casper

Several years ago, I was researching social and environmental impacts of chemical weapons disposal (Casper 2003). The U.S. was destroying its stockpile in accordance with the Chemical Weapons Convention. This research project included fieldwork on Johnston Island in the South Pacific and in Tooele, Utah. There, I learned from documents and informants that in the event of an accidental release of chemical weapons from the incinerator, residents were to “shelter-in-place” at home, in their workplaces, or even in their cars. In fact, they were encouraged to seal themselves into their cars with plastic and duct tape.

It frankly boggles the mind how one might seal oneself inside a vehicle, even with versatile duct tape. (And do so very quickly, because nerve gas moves through air.) But the logistics of the plan were less important to officials than the idea of the plan. This was the chemical weapons equivalent of the Cold War’s “duck and cover” campaign. Here, we see the illusion of safety over safety itself, implemented near a facility burning deadly chemicals, mostly sarin and VX, a tiny whiff enough to maim or kill a person.

On September 11, 2001, after Flight 767 crashed into the north tower of the World Trade Center, alarmed occupants of the south tower who had begun to evacuate were encouraged to stay inside the building, where they would be “safe” from attacks. Some had made it the lobby when they were ordered back inside and upstairs, creating “confusion and a two-way rush along the panic-stricken arteries of life” (Vulliamy 2001). Instead of finding safety, thousands were killed and buried in rubble when the tower fell. The independent commission that later investigated 9/11 learned that less than one minute before Flight 175 crashed into the building, “authorities changed their earlier instructions and ordered an evacuation” (Dwyer 2004).

Of course, by then it was too late.

Now, with COVID-19, we again see “shelter-in-place” orders emerge as a containment strategy globally and in the U.S., which is now the epicenter of the virus with more than half a million confirmed cases. Early in the crisis, Washington, California, and New York, which saw significant deadly outbreaks, issued statewide stay-at-home orders; other jurisdictions followed suit, though responses remain uneven across the U.S. (“Lockdowns, closures” 2020). Where lockdowns are in effect, residents are encouraged to remain in their homes – to shelter in place – leaving only for “essential” purposes. But many workers are in industries where they must leave their homes, including health care, grocers and pharmacies, sanitation, and public safety.

To be clear, a highly contagious virus is neither a volatile chemical weapon nor an ideologically weaponized airplane. And, it makes solid epidemiological sense for people to physically distance. Sheltering in place in the United States, at this critical moment in the disease’s trajectory based on what we have learned from other countries, is smart and may minimize losses. Yet, as with chemical weapons and the lessons of 9/11, it is worth exploring what political and cultural work “shelter-in-place” orders actually do, above and beyond protection. That is, how does “shelter-in-place” function discursively, what meanings does it convey, and what vulnerabilities does it exacerbate?

“Shelter-in-place” orders hide structural deficits. An order to shelter puts the burden on individuals to behave in moral ways for the good of the collective. But sheltering in place neither absolves poor leadership nor resolves inadequate, unevenly distributed health care. An order to shelter can lessen the impact on health care systems, freeing up resources for the most gravely ill, but it does not relieve embodied legacies of inequality and health disparities. People who survive this pandemic will still be living with heart disease, cancers, and hypertension they had before the virus. Groups already at risk of dying prematurely, for example Black birthing women, will still be at risk.

Sheltering-in-place also relies on a gendered division of labor, while also invisibilizing and devaluing women’s work. In two-parent, same-sex households, women continue to do the heavy lifting with respect to children, meal preparation, and housework. In dual-career couples, with kids now at home due to shuttered schools and daycares, someone’s paid employment is going to slide. As economist Marilyn Waring argued, it is worth paying attention to who needs care, who does the caring, and how much we value this work. Women in the so-called sandwich generation, with children and aging parents to look after, will be especially affected by sheltering-in-place. Helen Lewis describes this labor, done mostly by women, as “a huge subsidy to the paid economy” (Lewis 2020).

Sheltering in place comes with another illusion, that of the safety of home. Indeed, for decades, many (but not enough) abused women have fled their unsafe homes for the safety and anonymity of domestic violence shelters. Being confined with an abuser during COVID-19 could be deadlier than the virus itself, especially with overburdened social services, law enforcement, and health care systems. With one out of three U.S. women already experiencing assault in their lifetime, during crisis they are even more at risk. TIME reported on one woman whose husband “threatened to throw her out onto the street if she starts coughing” (Godin 2020). Other women describe partners withholding money or medical assistance, and many report being physically assaulted. In China, officials reported a significant increase in domestic violence, with one advocate stating, “90% of the causes of violence are related to the COVID-19 epidemic” (Wanqing 2020).

The order to “shelter-in-place” undoubtedly reflects the gold standard in public health, and it may well save thousands of lives. But it is not benign. Indeed, sheltering in place may distract us from broader structural issues and solutions, while also further harming already marginalized people.

References

Casper, Monica J. 2003. “Chemical Weapons ‘Dispersal’? The Mundane Politics of Air Monitoring.” In Monica J. Casper (ed.), Synthetic Planet: Chemical Politics and the Hazards of Modern Life. New York: Routledge.

Dwyer, Jim. 2004. “9/11 Tape Has Late Change on Evacuation.” New York Times, May 17.

Godin, Mélissa. 2020. “As Cities Around the World Go on Lockdown, Victims of Domestic Violence Look for a Way Out.” TIME, March 18.

Koran, Mario and Sam Levin. 2020. “All Californians ordered to shelter in place as governor estimates more than 25m will get virus.” The Guardian, March 19.

Lewis, Helen. 2020. “The Coronavirus is a Disaster for Feminism.” The Atlantic, March 19.

Lockdowns, closures: How is each US state handling coronavirus? 2020, April 10. Al Jazeera. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/03/emergencies-closures-states-handling-coronavirus-200317213356419.html.

O’Grady, Siobhán, Rick Noack, Marisa Iati, Alex Horton, Miriam Berger, Katie Mettier, Michael Brice-Saddler, and Hannah Knowles. 2020. “Coronavirus: Live Updates.” Washington Post, March 20.

Vulliamy, Ed. 2001. “Anger of Survivors Told to Stay Inside Blazing Towers.” The Guardian, September 16.

Wanqing, Zhang. 2020. “Domestic Violence Cases Surge During COVID-19 Epidemic.” Sixth Tone, March 2.

Monica J. Casper is a Professor of Gender and Women’s Studies, Public Health, Sociology and Africana Studies at the University of Arizona. She is the author of the award winning book The Making of the Unborn Patient: A Social Anatomy of Fetal Surgery.

Prisons as a Public Health Threat During COVID-19 by Lucius Couloute

According to the World Health Organization, as of April 12th there are roughly 1.7 million confirmed cases of COVID-19, otherwise known as the coronavirus. This public health threat, which is particularly deadly for older individuals and those with compromised immune systems, has propelled national, state, and local policy shifts across the globe.

For some individuals the primary form of protection against the Coronavirus – social distancing – will be a relatively easy guideline to follow: stay in homes away from others and wait out the spread of the Coronavirus until officials deem it safe enough to revert back to something approaching normal. For others – those classified as essential workers, those who need to work in order to pay rent, or the homeless – social distancing may prove particularly difficult, potentially subjecting them to increased exposure to the virus.

One vulnerable, yet under-recognized, population is the incarcerated. Typically locked away in tight quarters, incarcerated people living in our nation’s prisons and jails are subject to unsanitary conditions, little access to fresh air, and physical closeness to other incarcerated people and correctional staff. Jails in particular, as first stops along the correctional continuum, present serious problems as police agencies and prosecutors continue to arrest and accuse people of low-level crimes: potentially exposing jail populations to the coronavirus with every new admission.

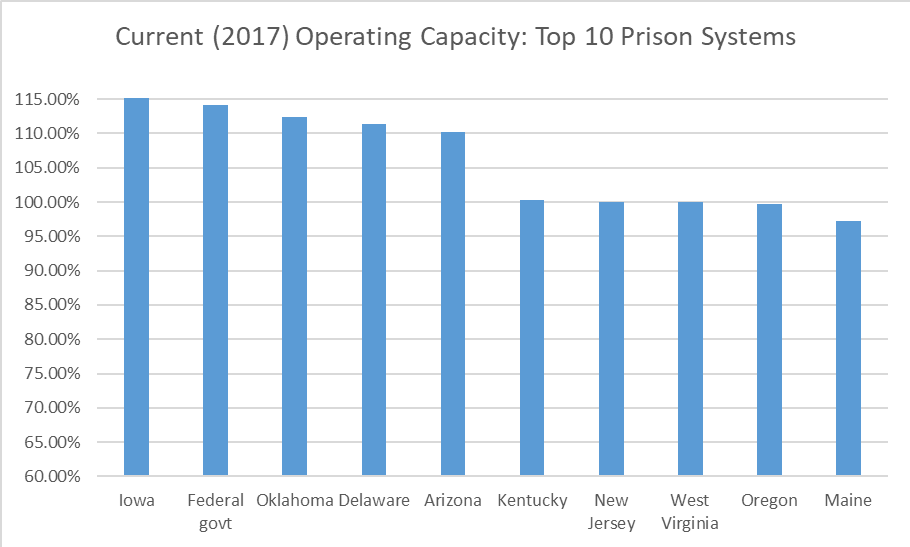

Due to decades of punitive policies and practices, prisons also present risks. Marked by increasingly cramped living spaces, prisons exhibit perfect conditions for the spread of any surface or airborne virus. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, for example, the federal government’s rated prison capacity is 135,792; the number of people in federal custody, however, is 155,006. In other words, the federal government is operating at 114% of their rated prison capacity and endangering the health of those forced to live in spaces designed to hold fewer people. It appears that many state prison systems are similarly situated, with incarcerated populations at or near their rated capacity.

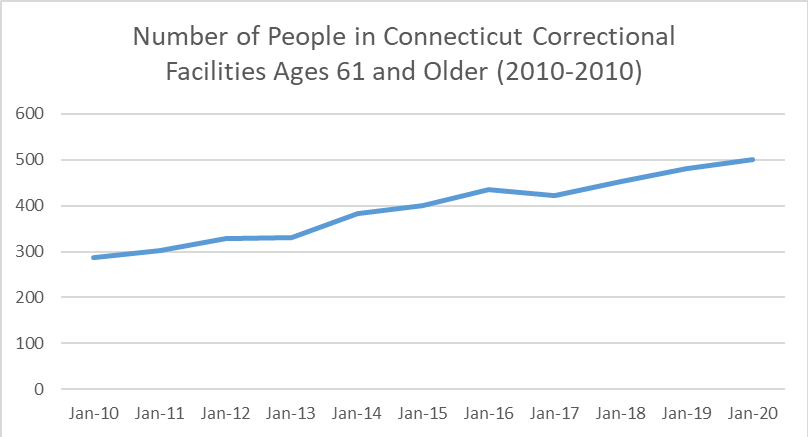

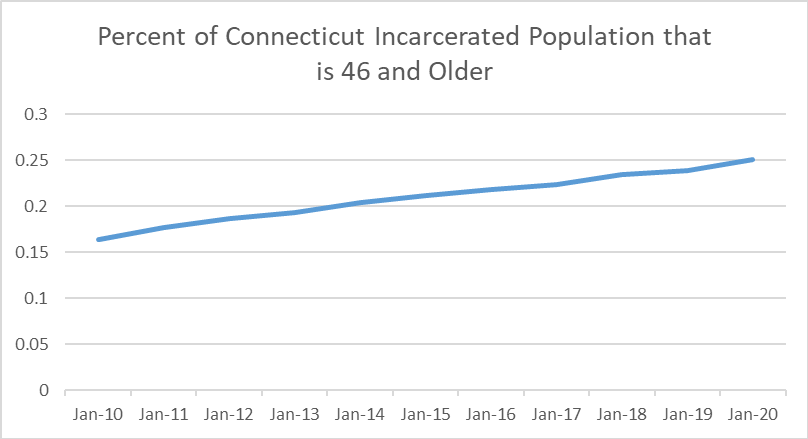

The problem, though, isn’t simply that we have too many incarcerated people in too cramped quarters. It is also important to recognize that during the last few decades, over-capacity correctional facilities have increasingly confined the population most susceptible to death via coronavirus: older adults and those with underlying health conditions. The state of Connecticut, for example, has experienced a 75% increase in the number of incarcerated people over the age of 60 in the last 10 years. A full twenty-five percent of Connecticut’s incarcerated population is now composed of those ages 46 and above.

According to recent research, a disproportionate number of incarcerated people are also dealing with health concerns like heart conditions, high blood pressure, and diabetes (Maruschak, Berzofsky, and Unangst 2015). Combined with well-known race- and class-based disparities in correctional populations, these trends suggest that correctional facilities are in-and-of-themselves a public health risk to poor, older, immune-compromised people of color.

If states and the federal government are to take these public health risks seriously, they must consider decarceration as the primary strategy to protect vulnerable populations. The status-quo is not acceptable. America’s experiment with mass incarceration certainly is not shielded from this fact. Locking humans away in tight cages with minimal thought toward public health reduces everyone’s safety (as is the case for correctional medical staff and their families).

Indeed, evidence from my recent interviews with formerly incarcerated people in Connecticut (prior to the COVID-19 pandemic) suggests that justice-involved people feel unsafe and unprotected when under the custody of the state. In one interview, Tony elaborates on this sentiment:

“It’s a lot of young brothers in jail with a virus that come from the street, and they don’t give you what you need. I seen people have heart attacks. All they do is they give you 800 Tylenol. That’s what their favorite thing is. You got to be on your death bed to go to UConn Hospital. You got to be literally [dead]. My boy from New Haven had a big tumor in his head, a big bump, and it was there for a whole year and they finally sent him to UConn after a year and got it cut out of his head. You see things like that […] An old man kept telling the nurse, ‘I got a pain in my chest’. She said it’s gas. Dude falls out and they take him to the hospital and he died that night, had a heart attack. So you see it’s against you. You got this system against you.”

If it is true that incarcerated people receive subpar medical services – and extant research appears to support this claim (Haber et al. 2019; Rich et al. 2015; Patterson 2013; Hotelling 2008) – states and the federal government should implement immediate changes to support the health and wellbeing of all of our communities, both on the inside and out. Recently, the Prison Policy Initiative drafted a list of policy recommendations:

- Release medically fragile and older adults.

- Stop charging medical co-pays in prison.

- Lower jail admissions to reduce “jail churn.”

- Reduce unnecessary parole and probation meetings.

- Eliminate parole and probation revocations for technical violations.

The social policies involved in maintaining mass incarceration are putting incarcerated people, correctional staff, and wider communities at risk during the current coronavirus crisis (and will likely continue to do so during future public health crises if nothing changes). In fact, reports from around the nation suggest that correctional officers and incarcerated populations are already experiencing coronavirus outbreaks – illustrating the need to take these carceral concerns seriously. Lawmakers and other officials should rapidly implement the above recommendations; act now to reduce the social and physical harms brought on by our nation’s reliance on mass imprisonment.

References

Haber, Lawrence A., Hans P. Erickson, Sumant R. Ranji, Gabriel M. Ortiz, and Lisa A. Pratt. 2019. Acute Care for Patients Who Are Incarcerated: A Review. JAMA Intern Med. 179(11):1561-1567.

Hotelling, Barbara A. 2008. Perinatal Needs of Pregnant, Incarcerated Women. J Perinat Educ. 17(2): 37–44.

Patterson, Evelyn J. 2013. The Dose–Response of Time Served in Prison on Mortality: New York State, 1989–2003. Am J Public Health. 103(3): 523–528.

Rich, Josiah D., Scott A. Allen, and Brie A. Williams. 2015. The Need for Higher Standards in Correctional Healthcare to Improve Public Health. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 30: 503–507.

Lucius Couloute is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Suffolk University, Boston where they research mass incarceration, criminalization, organizations, race and racism.

Homeless Children and COVID-19 by Yvonne Vissing and Diane Nilan

Homeless children are regularly out of sight, thus out of mind. These are the children who live in cars, motels, campgrounds, shelters, doubled-up with others, couch-surfing, and in places that are not safe or suitable for human habitation, yet are places they call home. In all the discussions of how the government is attempting to address the coronavirus, or COVID-19, homeless children aren’t even an afterthought. Their housing distress is not of their own making, yet they pay a high price for it. In a humane society, ensuring that their health is protected should be as vital a priority as for government officials’ children.

The US Department of Education’s National Center for Homeless Education identified over 1.5 million homeless children in 2018, an 11% increase over the previous school year and the highest number ever recorded nationally. These are just the children who could be counted, and does not include children too young to be in school, those who don’t attend school, and others who successfully mask that they are homeless. A conservative estimate is that there are 1.4 million children under age 6 who are homeless. At 3 million, they are, therefore, not an insignificant population. If they were old enough to vote, they would be large enough to be considered an important constituent group whose need could be courted by politicians.

Schools around the nation are being asked to close in order to stop the spread of the coronavirus. From an epidemiological perspective, it is imperative to stop the transmission of the virus, and keeping people from being in group settings is a realistic way to do so. The problem is, for homeless students it cuts off their main source of social stability and support. Barbara Duffield, Executive Director of SchoolHouse Connection observes that “For many of these children and youth, public schools are their best—and often only—source of support.” For most of these students, school is their only safety net, offering food, education, health and mental health services, caring adults, and a safe place to be during the day.

But homeless primary and secondary students aren’t the only ones who suffer when schools close–so do college students. Studies estimate that between 20% and 46% of college students may be housing insecure. Closing school for them is a problem too, because they lose their housing in the dorms and have nowhere else to go; they lose access to food, libraries, wifi, and can’t get their school work done either. In a country where over 41 million people regularly go hungry, school may be the place where children get their only meal. Minimizing gatherings to 50 or fewer people is difficult at a soup kitchen where countless people depend on a hot meal. For instance, at Portland, Maine’s largest soup kitchen they serve 300 people at each meal, where on any given night 400-500 men, women, and children are homeless. Imagine the exponential growth of this problem not just in big cities, but also in small towns and rural areas that don’t have many resources.

When schools and early learning programs close, or move to online learning, the health, safety, and well-being of homeless children and youth are jeopardized. If children live in shelters, often shelter rules require homeless people to leave early in the morning and cannot return until dinnertime. Schools provide a safety zone for children during that time, but when they are closed, where can children go to be safe and warm? When school is closed and students are told to do their studies online, it’s impossible if they don’t have a computer, smart phone, wifi access, especially if libraries, recreation centers and other places where they could go are closed.

The homeless population is at greater risk of getting sick. Poverty is associated with a host of preventable health problems. Respiratory problems, diabetes and other chronic diseases are common. Being homeless means being exposed to harsher environmental exposures. Hunger is a huge problem. People may not have a regular, safe place to sleep. Staying clean is a concern, whether showering, hand-washing or having clean clothes to wear. Having no place of their own to call home, they may be in shelters, doubled-up with others, or staying in places where there are lots of other people which exposes them to whatever health conditions others may have. So far, only one homeless person nationwide has tested positive for the virus. But homeless people are particularly likely to have additional health conditions that could exacerbate the impact of the illness, like asthma and other pulmonary conditions that put them at greater risk if exposed to COVID-19. When homeless children get sick, there may be no bed for them to sleep, no refrigerator for them to get a cool drink to help lower a fever, no stove on which to heat chicken soup. Homeless children and families have nowhere to shelter in place or be quarantined. In many states, unaccompanied minors cannot consent to or receive medical care of any sort.

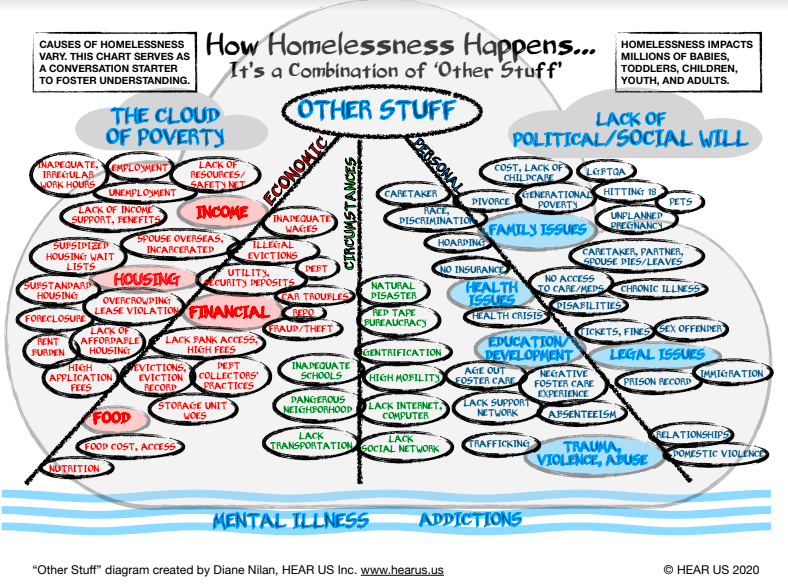

It is ludicrous to think that homeless children have the same resources or opportunities to survive a pandemic the same way as might middle and upper-class children. The following chart, designed by Diane Nilan, describes the multiplicity of factors that intersect to result in homelessness for children.

In almost all ways, society contributes mightily to the creation of homelessness, the social policies that are in place fail to either prevent it in the first place, or its failure to put forward the assistance necessary to actually do something about it. When the public laments “what can be done” about homelessness, the correct answer is “A Lot!” In our book, Changing the Paradigm of Homelessness, which examines the causes of homelessness and what can be done about it, we point out why so many strategies have failed–and we promote a paradigm change in how we treat homeless people that could actually prevent the majority of homelessness.

But our advice to change the paradigm about how we prevent and treat homelessness is falling on deaf ears. The White House and Department of Housing and Urban Development have to this point not moved to deploy emergency funding to help the homeless or housing shelters. The bipartisan agreement that was approved by the House did not include any measures aimed at the homeless, despite concerns raised by advocacy groups to congressional lawmakers. The measures announced by President Trump did not include any specific provision for the homeless. HUD Secretary Ben Carson reported that the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) would bear responsibility for handling a response to the potentially massive increase in need for shelters.

There is no long-range plan for people who are homeless, especially in the midst of the COVID-19 health crisis. Monies being provided in response to the coronavirus outbreak do not allow even one dollar to the homeless. Congress is acting on the “Families First Coronavirus Response Act” (H.R. 6201), which supposedly guarantees free coronavirus testing, secures paid emergency leave, enhances Unemployment Insurance, strengthens food security initiatives, and increases federal Medicaid funding to states. But Congress’s emergency spending bill entirely neglects the urgent needs of people experiencing homelessness according to Diane Yentel, president of the National Low Income Housing Coalition. “Providing resources to protect against an outbreak of coronavirus among people who are homeless is not only a moral imperative, it’s an urgent public health necessity.”

Ensuring that homeless children get the healthcare, schooling, and supports they need should also be a national priority. SchoolHouse Connection recommends the following supports be put in place immediately for homeless children:

- At least $300 million for the Education for Homeless Children and Youth (EHCY), with flexible uses of funds to meet the emergent, temporary housing, education, health, safety, and transportation needs of homeless children and youth whose schools have closed

- Increased early childhood and child care support for children and families experiencing homelessness

- Aid to college students to access to food, housing, health care, and child care, as well as devices and connection to the internet

- Emergency shelter, eviction prevention, and other housing assistance

In addition, we are supporting the request of the National Network for Youth for:

- At least $128 million for the Runaway and Homeless Youth Act program. Funding should bypass the usual competitive grant process, and be distributed to existing grantees, to help them provide temporary housing and health care to youth and young adults.

- At least $22 million for the Service Connection for Youth on the Streets. Funding should bypass the usual competitive grant process, and be distributed to existing grantees based on demonstrated need related to COVID-19 outbreaks.

There is a Chinese symbol that is translated to mean “out of crisis comes opportunity.” The COVID-19 pandemic is a crisis. Homelessness is a crisis for individuals who experience it, and for the nation as a social problem. These two crises have converged and demand our attention. They provide us an opportunity to do things that will help change the course of the future for the better for countless people. What will we do with this opportunity? We must wait and see.

Yvonne Vissing is a Professor of Healthcare Studies at Salem State University and Diane Nilan is the founder of HEAR US, a national non-profit organization providing voice and visibility to homeless children and youth.

Bodies in Places: Addressing Domestic Violence in a Pandemic” by Marie Laperrière and Kartikeya Bajpai

In the midst of the ongoing coronavirus crisis, several media outlets and political figures have spotlighted the need to examine how the pandemic affects domestic violence survivors. Such concerns are consistent with extant research suggesting that perpetration rates rise during periods of crisis. Early reports by women’s rights activists in both China and the US already point to increased calls to hotlines and victim services. Alarmingly, the rise in calls has also been accompanied by reports of domestic abusers using the epidemic to control and threaten their partners. In the short term, measures to combat the spread of coronavirus, such as social distancing, could increase the vulnerability of victims by cutting their ties to family and friends, and limiting their options for leaving abusive relationships. In the long term, the economic repercussions of the coronavirus outbreak could amplify victims’ economic dependence on their partners. While the negative consequences of the pandemic on survivors are manifesting in ways consistent with past scholarship, how state programs involved in the prevention of domestic violence will respond to the crisis remains to be seen.

Domestic violence preventive programs face an unprecedented challenge: how to provide much needed services while practicing social distancing. Having conducted research on Partner Abuse Intervention Programs (PAIPs) in Illinois for several years, I (first author) wondered how they would respond to these unique circumstances. PAIPs are preventive programs aimed at helping domestic abusers change their behavior by providing educational content delivered through weekly group meetings. They are also meant to ensure victim safety by exercising surveillance on participants and keeping victims informed of their progress in the program. With large numbers of abusers court-mandated to complete PAIP as a condition of probation or supervision, they are a central feature of the state’s response to domestic violence. I wondered how agencies providing PAIP would respond to the mandate to practice social distancing, and how changes would affect participants. My curiosity was also driven by the notion that breakdowns can be a source of learning about taken-for-granted organizational practices.

I reached out to PAIP facilitators only a few days after they received guidelines mandating them to practice social distancing. I expected to find agencies in a state of chaos, struggling to adapt their day-to-day operations. To my surprise, they seemed to have responded to the crisis very quickly and efficiently. There was no interruption of service: all facilitators I spoke to had moved their interventions online, conducting individual sessions virtually. Some programs were trying to figure out ways to conduct group meetings remotely, a practice they believed could be implemented shortly. This is not to say that they were not negatively impacted by the crisis. Facilitators expressed concerns with the wellbeing and health of their clients, and with the financial future of their agencies. Some found it slightly harder to “read” their clients over the phone, without the behavioral cues of in-person interactions. Employees also had to clock in more hours than usual in order to do individual phone calls with all of their clients. However, most were confident that they were able to “get the job done”. Perhaps most importantly, my respondents reported that, at least in their view, the clients themselves were satisfied with the changes.

The swiftness with which PAIPs moved to virtual meetings highlighted an organizational practice that was never questioned before: the mandate for participants to be physically present. State protocols stipulate that participants should meet in person and this practice was understood as a necessary burden by facilitators, participants, and even myself. However, through interviews with PAIP participants, I found that for the most disadvantaged, this burden was significant. Because the availability of affordable programs was limited, participation in PAIP often required a long commute. Moreover, criminal justice involvement meant frequent commute to attend court proceedings, meetings with probation officers and social workers, as well as other mandated treatment programs. In order to be physically present in all these spaces, some participants had to reduce their work hours, while others lost a job or dropped out of school. Many also reported how attending evening and weekend classes impacted their ability to be involved in their children’s lives. Finally, many lived in constant fear of violating their conditions of probation by arriving late or missing sessions or appointments. The fact that agencies adapted to remote meetings with minimal friction revealed that while it is typically understood as a necessary burden, the mandate to be physically present in different locations on a regular basis represents first and foremost a punitive practice.

PAIPs are typically described as therapeutic, less punitive alternatives to going to jail for individuals arrested for domestic violence and indeed, many of my respondents believed that they had benefited from the program. They described improved relationships with their partners, but also colleagues and family members, a new sense of self-awareness or an increased capacity to deal with anger issues and crises in their lives. However, for some, the cost of participation outweighed these benefits. Most importantly, the punitive dimensions of PAIPs and probation had effects that were counterproductive to the official goals of the program, which is to support and protect abuse victims. The burden associated with PAIP participation for the most disadvantaged participants often had important repercussions on their partners and children. The financial burden had a direct impact on participants’ capacity to provide for their families. During fieldwork, I regularly observed partners with young children waiting outside of the agencies for group meetings to end. Hence, the punitive effect of PAIP was felt by entire families. This should be cause for concern considering studies showing how financial distress and work-life balance issues can strain relationships and heighten the incidence and severity of domestic abuse.

It is important to note that researchers often accept the narratives that support organizational practices, potentially failing to see how punishment is supported by routine practices widely seen as unchangeable. However, crises and systemic breakdowns provide us with unique opportunities to distinguish between functional aspects of organizations and punitive practices disguised as necessary burdens. As Graham and Thrift note: “things only come into visible focus as things when they become inoperable” (2007, 2). Of course, we are not suggesting that PAIPs could or should shift to remote meetings entirely. There might be non-negligible benefits to meeting in person. However, it is worth thinking about the ways that technological solutions could be used to lift some of the burden imposed on PAIP participants and their families by criminal justice interventions. Many organizations responded creatively to the current crisis, and some of the strategies that they developed could be implemented in the longer-term.

While we highlight the justifications that underpin punitive practices in domestic violence prevention programs, similar examples abound in a variety of state-run programs. In recent weeks, social distancing efforts have led to media reportage on problematic practices in other contexts such as long waits in crowded courthouses, cramped spaces in migrant detention centers and the booking of people into prisons for crimes that represent a low risk to public safety – practices that normally go unnoticed. While the long-term effects of the coronavirus pandemic on domestic violence victims and programs will only reveal themselves in due time, we encourage researchers to utilize the current crisis and other disruptive moments to examine state-run processes and the punishments they needlessly enforce on the marginalized and disempowered.

References

Graham, Stephen, and Nigel Thrift. 2007. ‘Out of Order: Understanding Repair and Maintenance.” Theory, Culture & Society 24 (3):1-25.

Marie Laperrière is a Doctoral Student of Sociology at Northwestern University and Kartikeya Bajpai an Assistant Professor of Work and Organizations at EM Lyon Business School.

Return Migration During a Pandemic by Hansini Munasinghe

When the epicenter of the global covid-19 pandemic shifted to Italy in early March 2020, Sri Lankans living in Italy started migrating back to their country of origin. But when cases of returning migrants refusing to self-quarantine roiled media, public attitudes towards return migrants shifted quickly – Sri Lankan return migrants from Italy became the face of the pandemic in Sri Lanka. This brief case study of the Sri Lankan diaspora in Italy and their perceptions and experience of return migration as captured on social media, highlight the importance of studying return migration during and after this global pandemic.

Sri Lankan migration to Italy began in the 1970’s, with Catholic women from Sri Lankan coastal communities recruited for care work (Brown 2013). In the decades that followed, migration flows through family unification, employment, and undocumented migration (Brown 2013; Henayaka-Lochbihler and Lambusta 2004), has led to a well-established Sri Lankan diaspora in Italy. In 2016, about 109,968 Sri Lankan citizens lived in Italy (National Reports on the Main Foreign Communities 2016). Because these numbers do not include those of Sri Lankan origin who have obtained Italian citizenship, through birth or naturalization, the actual numbers of the Sri Lankan diaspora in Italy are likely much higher. Lombardia, the region hardest hit by covid-19, is home to the largest community of Sri Lankans in Italy – in 2016, more than 33,000 Sri Lankan citizens lived in Lombardia, making up about 31 percent of all Sri Lankan citizens living in Italy (National Reports on the Main Foreign Communities 2016).

It is important to note that while some Sri Lankans living in Italy returned, the majority remain in Italy, and with borders and airports blocked, are not able to return in the foreseeable future. However, in the aftermath of the highly publicized cases of return migrants refusing to self-quarantine, the Sri Lankan diaspora in Italy have witnessed the uproar and prejudice against them through news and social media. In a Facebook page for the Sri Lankan diaspora in Italy, a post made on March 22nd reads, “because of the faults of a few returning from Italy, our own people have become inhuman to the tears of 120,000 patriotic Sri Lankans who are living in Italy awaiting a death sentence.”

Challenges of return migration are not new to Sri Lankans living in Italy. Previous research has documented how returning migrants must navigate socioeconomic, cultural, and moral differences upon return, and navigate transnational identities and intergenerational relationships (Brown 2013). The perception that Sri Lankans return migrants from Italy brought covid-19 with them is added to an already contentious relationship.

The majority of Sri Lankans in Italy work in manual labor and the service sector, and often with precarious contracts and for low wages (National Reports on the Main Foreign Communities 2016). Even though their wages are meager in their host countries, the Sri Lankan economy relies heavily on remittances of foreign workers in the form of money sent back to family. In responses to the prejudice against return migrants, many in the Sri Lankan diaspora in Italy pointed to a disjuncture between Sri Lankan reliance on remittances while devaluing working class migrants. For example, in one video posted on social media and shared on a page for Sri Lankan diaspora in Italy, a man who appears very emotional and angry shares the following: