By Andrew Cohen

Much has changed for Tia Canlas ’11 since enrolling at Berkeley Law in 2008. But for this alum, one constant remains. “At every step, the school has supported my public interest career,” she said. “It’s provided me with access to mentors, resources and the experience I needed to launch my nonprofit.”

That nonprofit, the Alipato Project, is the first in California to provide legal representation to domestic violence survivors pursuing tort actions against their batterers. She founded the organization in 2012 and is now its legal director.

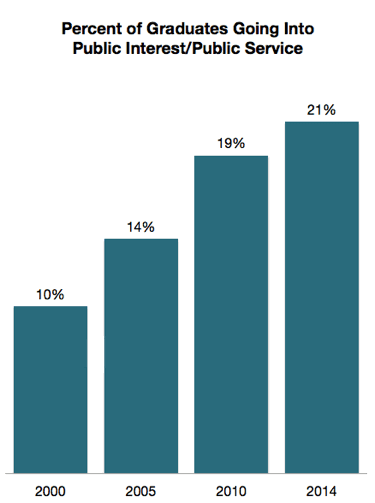

Canlas is among a growing number of Berkeley Law graduates pursuing public interest or public service careers. Over the last 15 years, the percentage of new alumni working in these areas has more than doubled. From the class of 2014, over 21 percent of graduates started their careers in public interest or public service—higher than all but one other Top 10 law school.

Alumni say that the combination of courses, externships, field placements, fellowships, student-led and faculty-directed clinics—along with career advice and a strong loan repayment program—create a well-paved runway for students who want to serve the public good.

As a Berkeley Law 1L, Canlas interned at the East Bay Community Law Center and was mentored there by longtime civil rights attorney Osha Neumann. That summer, she received the school’s Mary C. Dunlap Fellowship and Cynthia Dailard Public Interest Fellowship, allowing her to intern at the Transgender, Gender-Variant, and Intersex Justice Project.

In her second year, Canlas joined the law school’s Domestic Violence Law Practicum and worked with director Nancy Lemon ’80, “who inspired me to pursue civil lawsuits against perpetrators of domestic violence.” That enabled Canlas to volunteer at the Family Violence Law Center and represent clients in domestic violence court.

After graduating, Canlas gained more litigation experience at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission through Berkeley Law’s Bridge Fellowship. The fellowship provides short-term funding to graduates who are pursuing public interest careers—and do volunteer work toward that end while searching for permanent employment.

With the Alipato Project, Canlas represents middle- and low-income survivors and strives to increase awareness of civil law options for abuse victims. She credits Berkeley Law’s Loan Repayment Assistance Program (LRAP)—which lets students follow their career passion of helping the disadvantaged—for making it possible.

There are about 300 alums in LRAP, which erases the student loan out-of-pocket obligation for graduates who commit to qualifying public interest or government agency employment at a salary under $65,000 for 10 years. Those earning up to $100,000, or who work in public interest for less than 10 years, receive partial support. Berkeley Law’s $65,000 threshold for full support compares favorably to other top law schools, many of which reduce coverage at $50,000.

Leading the way

The school’s LRAP is a big reason why such a high number of graduates pursue public interest or public service law, “which is a real source of pride,’’ said alumna Valentina Restrepo ’14, an attorney at the Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery, Alabama. “It shows that the school’s social justice programs are succeeding.”

Restrepo jokes that she “milked Berkeley dry” on her own career path, saying, “I feel like Berkeley paid me to become a public interest lawyer.”

She obtained hands-on experience at two of the school’s Student-Initiated Legal Services Projects, which consist of two dozen pro bono projects founded and operated by Berkeley Law students. She also received $4,000 summer fellowships to work for the Contra Costa County Public Defender’s Office and the Southern Center for Human Rights.

Berkeley Law’s Summer Fellowship Program—for students working in approved, unpaid internships in public-interest, nonprofit or government sector law—has soared from 41 recipients in 2004 to 209 last year, when the school paid nearly $900,000 to cover the stipends.

After graduating, Restrepo received a year-long Berkeley Law Public Interest Fellowship, which supports public interest-minded graduates by funding them to work in a committed apprentice role for one year. Each year, the school budgets about $4 million for its LRAP, Summer Fellowship, Bridge Fellowship and Public Interest Fellowship programs—entirely from tuition revenue, with no contribution from the state.

“I wouldn’t be where I am now without the Public Interest Fellowship,” Restrepo said. “It did exactly what it’s supposed to—put you in an organization where you can prove your worth while helping people.” These days, Restrepo often talks with colleagues from other top law schools who are “blown away” by Berkeley Law’s public interest offerings, including its social justice curriculum.

“They didn’t have nearly the same number or quality of support initiatives, programs and courses as Berkeley,” she said. “I know Harvard and Yale Law grads who say, “Whoa, you had a class on Implicit Bias?’ They can’t even fathom it. The extent to which race-, gender- and equality-related issues permeate the school is inspiring. If people interested in public interest law do their research and compare the programs—especially LRAP—Berkeley seems like a no-brainer.”

Clinical Professor Jeff Selbin agrees. “Our experience is that the more public interest opportunities, resources and support we make available, the more our graduates choose public interest law careers,” he said. “Yes, we attract plenty of students who come in dedicated to using their law degree to serve society and to help people in need. But there’s a whole other group of students for whom that spark doesn’t ignite until they’re here, and they learn firsthand what a difference they can make in the real world.”