By Gwyneth K. Shaw

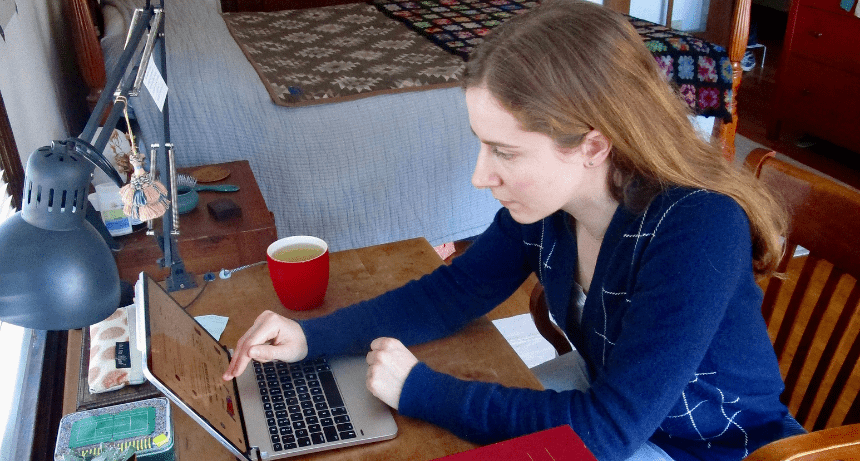

Berkeley Law student Clara Dorfman ’22 knows what a critical Election Day feels like: In 2016, she worked for Hillary Clinton’s campaign in the crucial swing state of Pennsylvania, engaging voters in the Pittsburgh area.

For the 2020 contest — with the stakes again breathtakingly high — Dorfman wanted to get involved. So when she heard about a project the Berkeley Human Rights Center was organizing to monitor social media for evidence of voter suppression and other threats, she eagerly volunteered.

More than 60 UC Berkeley undergraduate and Journalism School students, Investigations Lab alumni, and staff are working together in a virtual newsroom, monitoring Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, Tiktok, and more. They scour for evidence of violence, voter suppression or intimidation, and dis/misinformation, and feed that to the center’s partners, including Amnesty International and the news media.

Students worked from 7 a.m. to 9 p.m. on Election Day and the day after, collecting and archiving hundreds of relevant videos, photos, and posts from across the country. They’re continuing to monitor protests and violence related to the vote count.

“Capturing what’s happening on this critical day in U.S. history is a huge challenge,” says Alexa Koenig, executive director of the center and co-founder of its Investigations Lab. “Our Berkeley students have been trained to mine the internet for information in real-time, to identify misinformation and verify facts, and to collaborate with leading newsrooms and human rights organizations to ensure accurate information reaches the public.”

Here’s how Dorfman described her experience watching democracy face a major test in real time:

I had the Human Rights and War Crimes Investigations course I’m taking this semester — which is run by Alexa Koenig and Eric Stover of the Human Rights Center — on my radar since last year. I’d actually considered doing an international affairs masters program instead of a J.D., so when I came to law school I knew I wanted to explore the human rights course offerings and keep a foot in the international sector.

The course has been a phenomenal experience — for my paper in the seminar I’m working with a human rights investigator on a research project, which has been fascinating. And when Andrea Lampros, the center’s associate director and co-founder of the Investigations Lab, mentioned the Election Day project the lab was working on during a lecture she gave to our class, I asked if they happened to be taking volunteers.

The monitoring work itself essentially consists of just looking out for problems in real time: Searching for incidents of violence, misinformation, or intimidation, posts about people who might be experiencing issues at their polling place or getting turned away, or local media reporting on potential disruptions or protests at polls. Doing the work itself felt sort of like doomscrolling but with a higher purpose.

Fortunately, from what I witnessed and have since seen in media reports, it looks like this one turned out to be a relatively calm, peaceful election. Which was a huge relief, really. The systemic problems that persist in parts of the country still make it hard for many voters, of course. But there wasn’t the severity or number of incidents that I and I know lots of others were worried might result.

Whereas my campaign work in 2016 was more focused on advocacy — for the causes and candidates I believed in — election monitoring work is concentrated on ensuring that the nonpartisan process of voting goes smoothly. And, for me personally, it’s also a real comfort to know that Berkeley and Amnesty International and their partners are there, doing the important work of ensuring our democracy functions peacefully and successfully. It was an honor to be able to participate in that.