By Gwyneth K. Shaw

The art world is no stranger to the concept of reinvention — whether it’s style, medium, technique, or origin, the only constant is change. Art is also inherently a commodity, be it as a draw for museumgoers or an item to be bought at a gallery or auction.

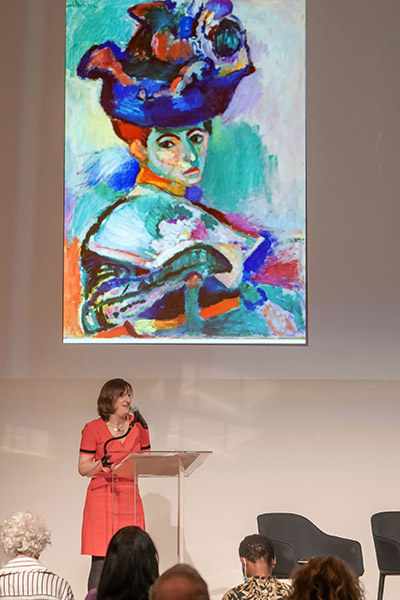

Opening the recent Berkeley Art, Finance, and Law Symposium, Adine Varah, general counsel of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), began with an image of a painting from 1905 that hangs on the museum’s walls: Claude Monet’s “Femme au Chapeau.”

The work was considered radical at the time because of its bold use of color, she said, but would hardly raise an eyebrow today. Similarly, while art and finance regularly outpace the law, much of what the industry is wrestling with now — from how to value art-based non-fungible tokens (NFTs) to whether images generated by artificial intelligence can be copyrighted — isn’t new.

Varah pointed to Marcel Duchamp’s provocative “Fountain” from 1917 as another example. It’s a signed urinal the artist submitted to needle the newly-formed Society of Independent Artists, which had pledged to exhibit every submission.

“Many of the fundamental questions of what is art, what is sold on the market, and how it’s being valued are questions that artists featured in our collection and on our walls have been raising for years,” Varah said. “It will be interesting to see 100 years from now what we think of NFTs — or if we think of them at all.”

The symposium, hosted by the Berkeley Center for Law and Business (BCLB), aimed to explore the frontiers of the high-end art world, where NFTs of cartoon apes fetch a $2 million price tag and a boom in bidders from around the globe pushed the spring art auction season into the stratosphere.

“This subject pulls in a lot of people from a lot of different backgrounds,” said BCLB Associate Director Delia Violante, who’s passionate about art law and art markets and proposed and organized the symposium. “Law ties together issues related to art such as intellectual property, financial regulation, fraud and authentication, and the preservation of cultural heritage.”

New twist, or ‘old wine?’

The event brought together lawyers, art dealers, academics, critics, and movers and shakers from the tech world into the bright and high-ceilinged galleries of SFMOMA. Not surprisingly, opinions differed about whether the questions at hand are truly new.

Joe Roets, CEO and founder of the blockchain platform Dragonchain, said this “parallel universe” offers a way to make new rules to replace a broken system, allowing people involved in transactions to lead the way.

Other speakers were more dubious. Simon Frankel, co-chair of Covington’s copyright and trademark practice group and managing partner of the firm’s San Francisco office, said many of the issues amount to “old wine in new bottles” that can largely be addressed with existing law.

Berkeley Law Professor Sonia Katyal, however, did question whether a new reliance on “smart” contracts between buyers and sellers might create new conflicts with existing contract law, as well as intellectual property law. The concept of fair use — the ability to use a copyrighted work under particular conditions without the copyright holder’s permission — is “potentially foreclosed by the blockchain,” she said.

Then there’s the AI question. The U.S. Copyright Office won’t grant copyright to something created solely by a machine. But if well-trained algorithms can create a painting based on written directions, what should happen?

Frankel offered an example: If one of his children opened his iPhone camera and altered the settings, and then snapped a photo of the conference, the resulting image would be copyrightable — even though, in his opinion, the photo took no creativity, which is supposed to be what copyright protects. And the AI painting would be ineligible.

What’s the right way to treat an AI creation, wondered Nick Brown of SuperRare, an NFT commerce platform: as “the most advanced paintbrush to date” or an artist in its own right?

These questions continue to steer the discussion back to the elemental one, Katyal said.

“If you speak to artists, or you speak to collectors or investors, there are very different views about what the function of art is, and I think that’s the world that we’re confronted with,” she said. “The increasing commodification of art has really changed the stakes in answering that question.”

Breaking new ground — again

These were the kinds of conversations organizers were hoping to spark.

“It was pathbreaking,” said Professor Frank Partnoy, a BCLB faculty co-director, who conducted a riveting conversation with New York art world titan Ann Freedman, featured in a recent film and podcast.

Partnoy likened the symposium to BCLB’s FraudFest, another unique concept that has become a high-demand event. (This year’s edition is July 11.)

“Like so many UC Berkeley events, it was an example of how our convening power and multidisciplinary approach can bring together people who might not otherwise talk and learn from each other,” Partnoy said.

Holding the event at SFMOMA made for a spectacular day, visually and intellectually, he added.

Violante spent years polishing the concept for the symposium, building on the connection between art and law and discovering along the way that others shared her passion. BCLB Executive Director Adam Sterling ’13, Partnoy, and others supported her efforts, which she hopes will one day lead to the creation of a law and art institute at Berkeley Law.

“Art can influence the way we think, view the world, and embrace the many voices and perspectives around us. Art gives a sense of belonging and purpose,” she said. “There’s so much to think and talk about, and Berkeley Law should own this space.”