By Susan Gluss

Consumers are easily fooled by ads masquerading as editorials, according to a new paper by Chris Jay Hoofnagle and Eduard Meleshinsky ’14. Their research shows that these “native ads,” better known as advertorials or clickbait, are becoming harder to differentiate from actual news content. Yet they’re proliferating online at a rapid rate.

These specious ads put consumers at risk, said Hoofnagle, the faculty director of the Berkeley Center on Law & Technology (BCLT). “It’s well established that when consumers realize that content is advertising, they’re more skeptical of it. But if you can mask the advertising content, people drop their defenses,” making them more vulnerable to false claims, he said.

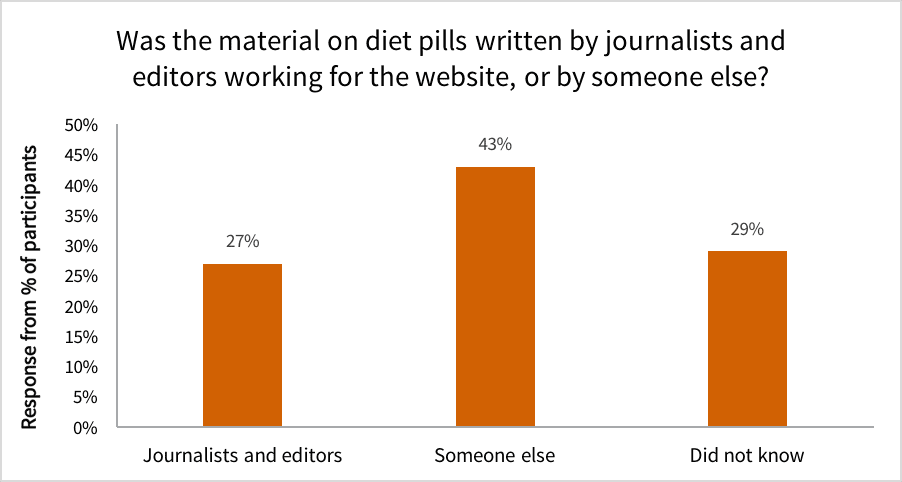

Hoofnagle and Meleshinsky surveyed nearly 600 consumers with a typical advertorial embedded in a blog. They found that 27 percent of respondents thought it was written by a reporter or an editor, while another 29 percent weren’t sure. Although the ad was marked “sponsored content,” it failed to raise a red flag.

It wasn’t just the layout and font style that tricked readers. The use of color and composition also played a role. For example, the co-authors compared two pullout quotes on the benefits of a diet pill along with a photo of a smiling spokeswoman. In one photo, she appeared in front of a plain white background; in the other, a shelf of blue containers. When she stood before the small containers, sixty percent of consumers thought she was a medical expert, versus 23 percent with a plain white background.

FTC guidelines

Hoofnagle first alerted the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) of the survey’s preliminary results in 2013. Last month, the agency issued new guidelines on “deceptively formatted” ads just a week after his paper was published.

“People browsing the Web, using social media, or watching videos have a right to know if they’re seeing editorial content or an ad,” said Jessica Rich, director of the Bureau of Consumer Protection, in an FTC press release,

Hoofnagle said the guidelines are mostly a restatement of existing law, with an important caveat. “The key point is that the FTC is telling advertisers to use the word ‘advertisement’ when it discloses native advertising,” he said. “This is really important because the current terms, such as ‘sponsor content’ or ‘promoted host,’ are too ambiguous.”

The new guidelines are a sign that the FTC is poised to take legal action against deceptive advertorials, Hoofnagle said. “You don’t need a bleeding body to win one of these cases. What you need to show is detriment: a consumer buys a product she ordinarily wouldn’t buy and pays a higher price,” than comparable products.

But Hoofnagle and Meleshinsky want to go one step further: banning advertorials entirely, based on consumer psychology and the FTC’s paltry history of policing misleading ads.

“Native advertising may not appear to fit the rubric of an illegal deceptive trade practice at first,” said Meleshinksy, an attorney at Bryan Schwartz Law and a former BCLT fellow. “But our findings suggest that even with a prominent disclosure, a substantial number of consumers are unaware of the commercial nature of advertorials.”

Since the FTC is unlikely to ban native ads, other approaches could work, Hoofnagle said, such as putting the onus on publishers to prove that advertorials aren’t misleading.

This paper is the duo’s first in a series on consumer vulnerability and targeted marketing. The field is ripe for study since “there’s far more false advertising than can ever be policed by the FTC,” Hoofnagle said.

The old maxim still applies today: buyer beware.