By Andrew Cohen

While the corporate law experts at Berkeley Law’s April 4 conference on shareholder activism offered different opinions about causes and impacts, they all found a patch of common ground: it’s here to stay.

Active shareholders assert their power as owners of a public company in order to change its behavior and encourage corporate responsibility, and their actions have increased dramatically in recent years. Triggering factors include sub-par share price performance, overly conservative financial strategies, and conglomerate business models. Since 2009, activist hedge funds have outperformed traditional hedge funds and other markets—forcing board rooms to take notice.

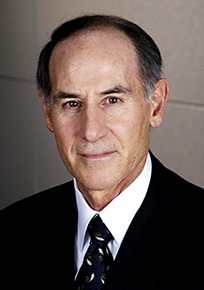

The conference, co-sponsored by the Berkeley Center for Law and Business and the Berkeley Business Law Journal, illuminated this shifting landscape. Keynote speaker Larry Sonsini ’66, chairman of Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati, described how companies must adjust to these changes.

“This is a very live topic in today’s board rooms,” said Sonsini, a renowned corporate governance expert who has played a lead role in many of the most notable IPOs, mergers, and acquisitions of Silicon Valley and beyond. “It’s very clear to me that we’re in a sea change.”

Activist shareholders acquire stakes in publicly traded companies for reasons ranging from making short-term profits on share prices to effecting policy changes to comport with social and environmental goals. Activists typically seek changes in management, such as replacing a company’s CEO or board members, or in “financial engineering”—pushing the company to buy back shares, raise dividends, or sell off underperforming divisions.

“Performance metrics are changing as a result, with a greater priority on short-term gains,” Sonsini said. “That can be to a company’s detriment over time because it leads to unhealthy risk aversion, which jeopardizes long-term performance. Look at all these new disruptive technologies. What Amazon is doing to e-commerce, what Uber and Lyft are doing to the taxi industry—that’s very disruptive. There’s a desire to monetize short-term before things change dramatically because technology has the life-cycle of a banana nowadays.”

On the positive side, Sonsini noted that shareholder activism often promotes strong corporate governance, and panelists touted the benefits of constructive tension in the board room. Given the high returns experienced by the activist sector, such involvement is predicted to expand further—to larger companies and more parts of the world.

Checks and balances

Sonsini also said shareholder activism has forced more transparent communication within companies, leading to clearer, more detailed management reports. He added that this has led to greater emphasis on process: research analysts are more willing to challenge companies, boards are reluctant to have a director for more than nine years, and companies are more vigilant about potential conflicts of interest.

As an example, Sonsini recounted an exhaustive, independent report that exonerated Oracle CEO Larry Ellison of insider trading accusations. A Delaware court threw out the report—after praising it—simply because two of its three authors had strong ties to Stanford, where Ellison is a known contributor.

The conference, which convened regulators, attorneys, academics, and business professionals, featured three panels. One of them, moderated by Berkeley Law Professor Eric Talley, addressed the future of shareholder involvement in the U.S. and developing countries.

“Shareholder activism is here to stay because institutional investors view it as an asset class,” said K&L Gates partner Mark Perlow, whose practice focuses on investment management and securities law. “People who manage mutual funds are increasingly willing to support activists. They share a point of view that these corporations need to be shaken up. It’s a marriage of convenience. I see my clients increasingly inclined to support shareholder meetings.”

UC Davis law professor Afra Afsharipour explained how such activism is starting to take hold overseas. “Six years ago I would’ve called it a non-factor in India, for example, but we’ve seen a change in the regulatory landscape there and India’s version of the SEC supports it. Shareholder engagement is a true requirement for companies there now.”

Talley noted that shareholder activism has changed considerably over the last 20 years—seeping into more layers of a company’s operation. “It used to be more of a low-level activity, but has scaled up considerably,” he said. “Now it’s more sophisticated with multi-year strategies, and demands our attention.”